Sicily: Culture and Conquest, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Sicily: Culture and Conquest, British Museum

Sicily: Culture and Conquest, British Museum

For centuries, invading armies, migrants and merchants have shaped the art of Italy's southern outpost: can an exhibition do it justice?

This exhibition – the UK's first major exploration of the history of Sicily – highlights two astonishing epochs in the cultural history of the island, with a small bridging section in between. Spanning 4,000 years and bringing together over 200 objects, it aims to "reveal the richness of the architectural, archaeological and artist legacies of Sicily", focusing on the latter half of the seventh century BC and the period of Norman enlightenment, from AD1000 to 1250.

For anyone who has visited Sicily’s ancient archaeological sites of Segesta, Agrigento and Selinunte, which still boast some of the grandest temples built anywhere in the Greek Mediterranean – or who has experienced the exquisite medieval mosaics of Palermo and Monreale – this promises to be a treat of a show. I must, therefore, confess to being slightly disappointed. There are some remarkable objects – such as an almost perfectly preserved terracotta altar with three goddesses, associated with the ancient Greek cult of Demeter and Persephone (pictured below right), and an exquisite medieval cameo of Noah and his Family Entering the Ark – but the main impression is one of a stimulating thesis illustrated by an array of examples of varying visual impact. These are nonetheless many fine objects from the British Museum’s own collection and beyond, and some notable Sicilian loans that have not been seen in the UK before.

The exhibition’s thesis is certainly worth expounding. And its message is a timely one. As one of the curators reminded us at the press view, Sicily is so much more than holiday beaches, blue skies, oranges, lemon trees – and mafia! What now makes it such a poignant crossing point for refugees, historically made it a central Mediterranean magnet for settlers travelling from the Eastern Mediterranean and Northern Europe. Over the centuries, this influx of people has given the island a distinct and unusually rich cultural character, born from the imaginations and influences of many races and people. A 12th-century Arab geographer described Sicily as “the pearl of the century”, a unique place that “brings together the best aspects from every other country”.

The exhibition’s thesis is certainly worth expounding. And its message is a timely one. As one of the curators reminded us at the press view, Sicily is so much more than holiday beaches, blue skies, oranges, lemon trees – and mafia! What now makes it such a poignant crossing point for refugees, historically made it a central Mediterranean magnet for settlers travelling from the Eastern Mediterranean and Northern Europe. Over the centuries, this influx of people has given the island a distinct and unusually rich cultural character, born from the imaginations and influences of many races and people. A 12th-century Arab geographer described Sicily as “the pearl of the century”, a unique place that “brings together the best aspects from every other country”.

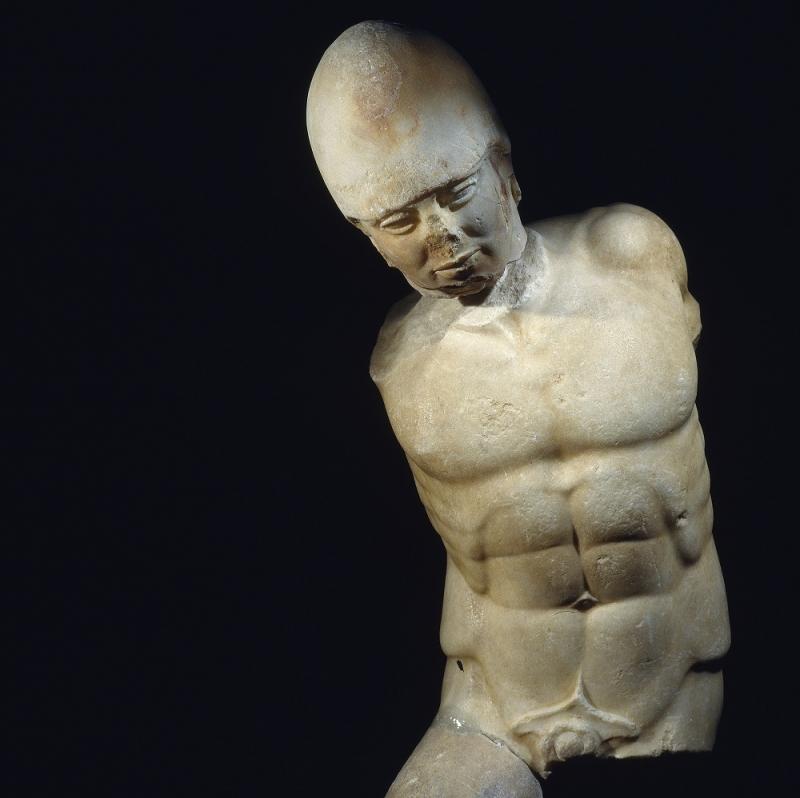

Sicily’s stunning natural beauty, rich resources, and fertile soil, fed by the volcanic dynamic of Mount Etna, made it highly attractive to mercenaries, tyrants and conquerors. Occupiers included Vandals (476AD), Ostrogoths, Byzantine generals, Greek tyrants, Phoenician and Punic settlers, Arab raiders, Roman commanders, Christian Byzantines, Muslim Arabs and Norman Kings. The Sicilian Greeks built astonishing temples (still remarkably intact survivals) and assiduously adapted Greek subjects and themes from one medium (such as marble – which was a scarce commodity on the island) to another. The exhibition includes several of such artefacts, including a terracotta altar with a virile lion “precision-killing” a bull (the animal of sacrifice), one of the key loans from Sicily. The powerful relief sculpture echoes architectural temple friezes in Greece and Turkey, while providing a stirring simile of subjugation and conquest. Another major loan from Sicily is an iconic marble statue from ancient Akragas – modern-day Agrigento – of an austere helmeted warrior (main picture).

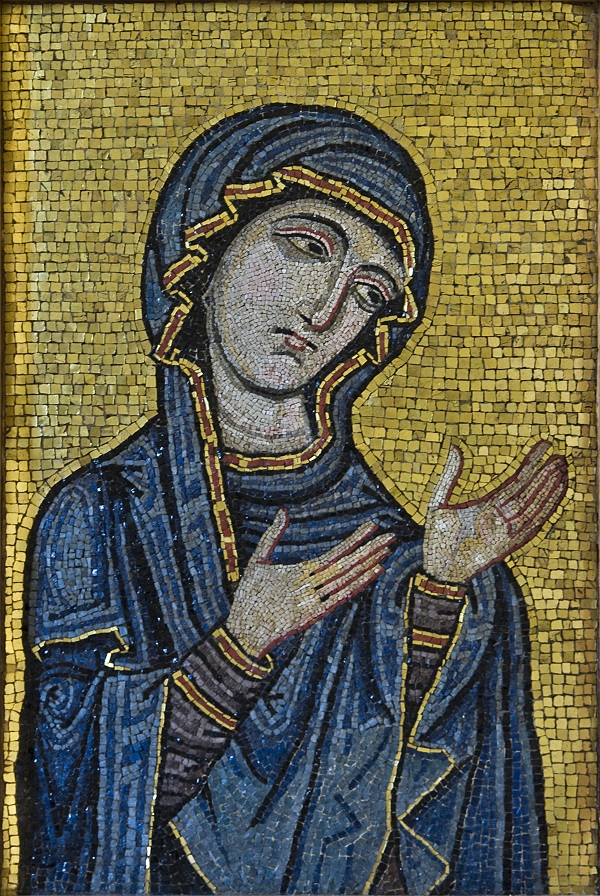

But it is the Normans who perhaps provide the most fascinating content in the exhibition. Having conquered Sicily in 1061, they transformed its culture, much as they transformed English culture from 1066 onwards. The Norman occupiers pursued a shrewd and deliberate policy to encompass all the peoples in their kingdom – such as Arabs, Italians, Jews – and this is reflected in the unique climate of multicultural collaboration that they fostered. Multilingualism was also a feature of Roger II’s kingdom; the exhibition includes a marble, porphyry and glass decorated tombstone (1149) with a funerary eulogy written in Judaeo-Arabic, Latin, Greek and Arabic – a mark of respect for the four cultures and religions. Under Roger II an extraordinary architecture emerged, combining Norman and Arabic influences, with Byzantine style mosaics and wooden Islamic influenced architectural decorations. The show includes a mosaic of the Madonna as Advocate – all that remains of the mosaic decoration of Palermo Cathedral, made during the reigns of Roger II and William II (pictured above left).

But it is the Normans who perhaps provide the most fascinating content in the exhibition. Having conquered Sicily in 1061, they transformed its culture, much as they transformed English culture from 1066 onwards. The Norman occupiers pursued a shrewd and deliberate policy to encompass all the peoples in their kingdom – such as Arabs, Italians, Jews – and this is reflected in the unique climate of multicultural collaboration that they fostered. Multilingualism was also a feature of Roger II’s kingdom; the exhibition includes a marble, porphyry and glass decorated tombstone (1149) with a funerary eulogy written in Judaeo-Arabic, Latin, Greek and Arabic – a mark of respect for the four cultures and religions. Under Roger II an extraordinary architecture emerged, combining Norman and Arabic influences, with Byzantine style mosaics and wooden Islamic influenced architectural decorations. The show includes a mosaic of the Madonna as Advocate – all that remains of the mosaic decoration of Palermo Cathedral, made during the reigns of Roger II and William II (pictured above left).

There are perhaps some missed opportunities: a colossal marble head of the most enlightened and erudite ruler of all, Frederick II – Norman King of Sicily and later Holy Roman Emperor, could have been dramatically paired with the magnificent bronze head of Augustus in the British Museum’s own collection (unfortunately on loan elsewhere). Through this comparison we would have vividly grasped Frederick’s full-blooded revival of the cultural language of imperial Rome, which included the rebirth of the refined art of cameo and the production of prized gold coins with imperial-style profile portraits. But, as the exhibition amply demonstrates, Frederick’s admiration for Rome did not prohibit an equal appreciation of Arabic and Byzantine cultures.

The show ends rather abruptly, with a 15th-century Renaissance painting of the Virgin and Child by Antonello da Messina, about 1460–9, an example of isolated achievement during Sicily’s sparse Italian Renaissance period. One is left with an impression of fragments – of art, of history, of Sicily’s rich exchange with other cultures – and memories of the lemon yellow, blue and terracotta of the exhibition design, associated with the Sicilian lemons, terracotta buildings and blue skies that we know of old.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment