It is sobering to think that the medieval and Renaissance paintings that fill our galleries represent just a fraction of the artistic output of that period. Panel paintings – not to mention exquisitely fragile wall paintings – have for the most part succumbed to the ravages of time, and those not destroyed by fire or flood, acts of war or vandalism, or abortive attempts at restoration have simply faded, darkened or discoloured.

Safely tucked away in libraries, illuminated manuscripts have survived in far greater numbers and, as such, form the most substantial, if most easily overlooked, legacy of medieval and Renaissance visual culture. The bland anonymity of a bound volume shelved amongst thousands was not much of a draw for the vandals and looters of the past, and served to shield the richly decorated pages from light and the elements.

Of the world’s many illuminated manuscript collections, that of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is reputedly the finest, the books cocooned in fenland isolation, the terms of the founder’s bequest ensuring that much of the collection remains forever inside the museum (pictured right: The Macclesfield Psalter, c.1330-1340).

Of the world’s many illuminated manuscript collections, that of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is reputedly the finest, the books cocooned in fenland isolation, the terms of the founder’s bequest ensuring that much of the collection remains forever inside the museum (pictured right: The Macclesfield Psalter, c.1330-1340).

In this spellbound state, the Fitzwilliam perpetuates the conditions that have kept these books safe for centuries, and the knowledge of this makes looking at them a strangely timeless experience. In galleries darkened to protect light-sensitive pigments, pages embellished with gold and silver leaf twinkle convincingly, just as they must have done when seen by candlelight.

Unlike our encounters with easel paintings, there is an authenticity of experience that comes from the simple interaction between viewer and book, a relationship so fundamental that it seems innate. Even so, there are considerable difficulties involved in the display of books, and glass cabinets inevitably introduce a frustrating barrier to the appreciation of these exquisitely detailed objects.

The museum has chosen this bicentenary year to celebrate not only the riches of its collections, but its pioneering work in recording and investigating its illuminated manuscripts which span the sixth to the 16th centuries. Its crowning achievement is Illuminated, an ongoing project to record the collection in a free, publicly accessible database combining high-resolution images with a vast array of information in a well-designed, easily navigable format. It includes the results of new, non-invasive analytical techniques which have yielded fascinating and unexpected information about the materials and methods of manuscript illumination.

Illuminators were traditionally thought to have used a fairly limited range of pigments, but the Cambridge project has shown the opposite, with artists deploying the sort of varied and complex mixtures more often associated with easel painting. The discovery of smalt, a cheap blue pigment made by grinding up glass, in a Venetian manuscript, suggests an artist as pragmatic and versatile as any panel painter, making use of a local, readily available material.

In another beguiling example, an eagle marks the beginning of an eighth-century St John’s Gospel, the intricate but spare design with large areas of blank parchment typical of manuscripts made at Lindisfarne. We are told that the organic purple used to colour the eagle’s head is derived from a lichen found locally, over which yellow orpiment has been applied in dots. The contrast between the local purple, and the rare, imported yellow is evocative, and shows that for all its isolation Lindisfarne was part of an international trade network. But it also shows the technical expertise of the Lindisfarne illuminators, who knew that the organic purple base would prevent the deterioration of the orpiment, an unstable pigment that would otherwise tend to turn black.

In another beguiling example, an eagle marks the beginning of an eighth-century St John’s Gospel, the intricate but spare design with large areas of blank parchment typical of manuscripts made at Lindisfarne. We are told that the organic purple used to colour the eagle’s head is derived from a lichen found locally, over which yellow orpiment has been applied in dots. The contrast between the local purple, and the rare, imported yellow is evocative, and shows that for all its isolation Lindisfarne was part of an international trade network. But it also shows the technical expertise of the Lindisfarne illuminators, who knew that the organic purple base would prevent the deterioration of the orpiment, an unstable pigment that would otherwise tend to turn black.

While all of this is beautifully explained in the exhibition, the book itself is displayed so far back in its case and with lighting so low, that the painted details are simply not discernible, and can only be appreciated by consulting a reproduction.

Other revelations are equally problematic because they rely too heavily on lengthy captions and are essentially non-visual. Infra-red imaging has revealed instructions written in Dutch or German beneath the lavishly decorated frontispiece of a 15th-century Parisian encyclopaedia (pictured above), showing that the illuminator and his workshop were not French but immigrants from the north. It is interesting, certainly, but it is not what we see in front of us, and for that reason it sits far more comfortably in the catalogue or for that matter, in the Illuminated database.

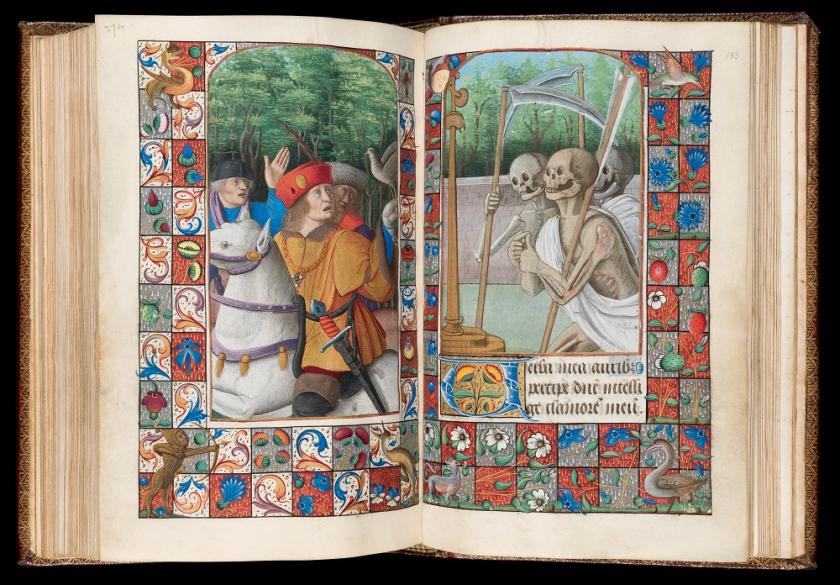

It is an unfortunate irony that an exhibition of books should be dominated by captions and wall texts so long and numerous that they threaten to become the principal focus, but The Three Living and the Three Dead from a French Book of Hours, c.1490-1510 (main picture), big and bold enough to be enjoyed despite the glass, is a reminder that reading can wait. Above all, an illuminated manuscript like this is a visual experience, a fine piece of painting that uses the format of the book as a dramatic device to fascinate and delight the viewer.

The Fitzwilliam has a huge amount to celebrate and be proud of, and there are the makings of several more focused exhibitions here, shaped by the museum’s groundbreaking research programme. This is rare and wonderful opportunity to see some exquisite treasures: buy the catalogue and do the reading when you get home.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment