Cymbeline, RSC, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Cymbeline, RSC, Barbican

Cymbeline, RSC, Barbican

New Brexit tones give novel direction to Shakespeare's late romance

“Britain is a world by itself.” It could be the slogan of the year – and rather longer, probably – but the phrase comes from Shakespeare’s late romance Cymbeline. Its Act III scene, in which Britain announces that it is breaking its allegiances to the Roman Empire, surely can’t ever have played before with quite the nuance that Melly Still’s RSC production gives it.

Back in 1609, Britishness was the issue, too, but coming from the opposite direction: James VI of Scotland was new on the English throne, and the matter to hand was unifying those two worlds into a single whole. Cymbeline endows the idea of Britain with a nobility that harks back to a mythic past – the Welsh scenes of the second half – here set against the baseness of the present. “And we will nothing pay/For wearing our own noses,” that quotation continues, as the dullard Cloten taunts the protocols of negotiation, his intonations cocking a snook at the status quo in a way that could be coming right out of the mouths of UKIP.

If there’s one thing that’s gone missing from this production, it’s a sense of Shakespeare’s poetry

If Still’s vision of Cymbeline’s Britain hints at a state-of-the-nation quality, we should look out for where we’re heading: it’s a dystopian vision of a world in decay. The director has adapted the original, not least in changing the gender of its ruling tandem: Cymbeline is now a queen, rather punkily clad à la Derek Jarman, firmly played by Gillian Bevan, her consort becoming the Duke (James Clyde, borrowing bits of his wardrobe from Sherlock). It gives us one line, “A mother cruel and a step-dad false”, that certainly isn’t there in the folios. That change works quite nicely, the mother’s feelings about her two lost sons (well, a son and a daughter here) adding pathos to one strand of the many closing revelations, while Clyde’s character is now less parodic step-mother, more Jacobean plotter.

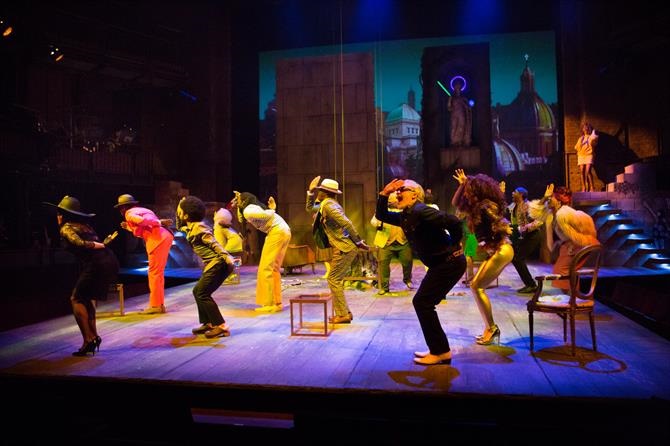

Giving that older generation a mannered quality brings home the youth of Cymbeline’s main players, and this production certainly aims for young energy, ensemble dance scenes included (pictured below), which sometimes comes at the expense of subtlety. Posthumus (Hiran Abeysekera) seems barely to have come of age, his physical slightness dominated by the greater stage presence of Innogen (Bethan Cullinane, impressive: if any character develops in the course of the play at all, it’s her). Changing the gender of Posthumus’s male servant to make her Pisania (Kelly Williams) alters the dynamic of that master-attendant relation, the result coming closer to, say, Juliet and her nurse. But it’s when the exiled Posthumus arrives in Rome that the fun really starts for Still and designer Anna Fleischle. This is a decadent, almost Eurotrash world that recalls Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty – just as Posthumus’s later bloodied tutu surely nods to Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan. I’m not sure whether translating the words of the notional Dutchman, Frenchman and Spaniard who make up Roman society into their native tongues, with English surtitles, adds anything more than novelty; the same applies to exchanges between Roman and British leaders in Latin (although if no common language can be found for our future EU negotiations, who knows?).

But it’s when the exiled Posthumus arrives in Rome that the fun really starts for Still and designer Anna Fleischle. This is a decadent, almost Eurotrash world that recalls Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty – just as Posthumus’s later bloodied tutu surely nods to Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan. I’m not sure whether translating the words of the notional Dutchman, Frenchman and Spaniard who make up Roman society into their native tongues, with English surtitles, adds anything more than novelty; the same applies to exchanges between Roman and British leaders in Latin (although if no common language can be found for our future EU negotiations, who knows?).

Rome offers a rise in energy levels, too, with the appearance of Oliver Johnstone’s scheming Iachimo, all white-suited, dandy languor on the outside, undiluted cynical nastiness within. If Cymbeline’s good characters might be accused of lacking some, if not all, conviction, there’s no doubting the passionate intensity with which this devil pursues victory in his wager (pictured below, from left: Oliver Johnstone, Byron Mondahl, Hiran Abeysekera). The rapier-like insistence of Iachimo’s soliloquy in his invasion of Innogen’s bedroom has a welcome dramatic verve in a production where wider effects blunt rather than illuminate the text .

If there’s one thing missing, it’s a sense of Shakespeare’s poetry. Cymbeline may be a complex play – much more diverse and uneven than The Winter’s Tale or The Tempest – but some of its accents and intonations are richer than we find them here, especially in the first half. The emergence into the open air of Wales is very welcome: the artifice comes down a note or two, allowing the language to speak for itself which, in the delivery of Belarius and his brood, it does. Composer Dave Price’s music, coming from the upper-stage wings, has richness of atmosphere throughout but comes into its own here, as do the more organic shapes and hues of Fleischle’s design.

If there’s one thing missing, it’s a sense of Shakespeare’s poetry. Cymbeline may be a complex play – much more diverse and uneven than The Winter’s Tale or The Tempest – but some of its accents and intonations are richer than we find them here, especially in the first half. The emergence into the open air of Wales is very welcome: the artifice comes down a note or two, allowing the language to speak for itself which, in the delivery of Belarius and his brood, it does. Composer Dave Price’s music, coming from the upper-stage wings, has richness of atmosphere throughout but comes into its own here, as do the more organic shapes and hues of Fleischle’s design.

On occasion less might have been more. The Brexit allusion adds a dimension, and convinces as more than gimmick, which cannot be said of some of the production's theatrical elements. As the characters quit the stage, we’re left to ponder how relevant Cymbeline’s closing reconciliations may prove in real life – and just how long it will be before we hear anyone speaking another of the play’s uncannily apt lines, “Our kingdom is stronger than it was”, with any real conviction.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Add comment