Sunday Book: Jake Arnott - The Fatal Tree | reviews, news & interviews

Sunday Book: Jake Arnott - The Fatal Tree

Sunday Book: Jake Arnott - The Fatal Tree

Delicious, heart-breaking romp through the 1720s underworld

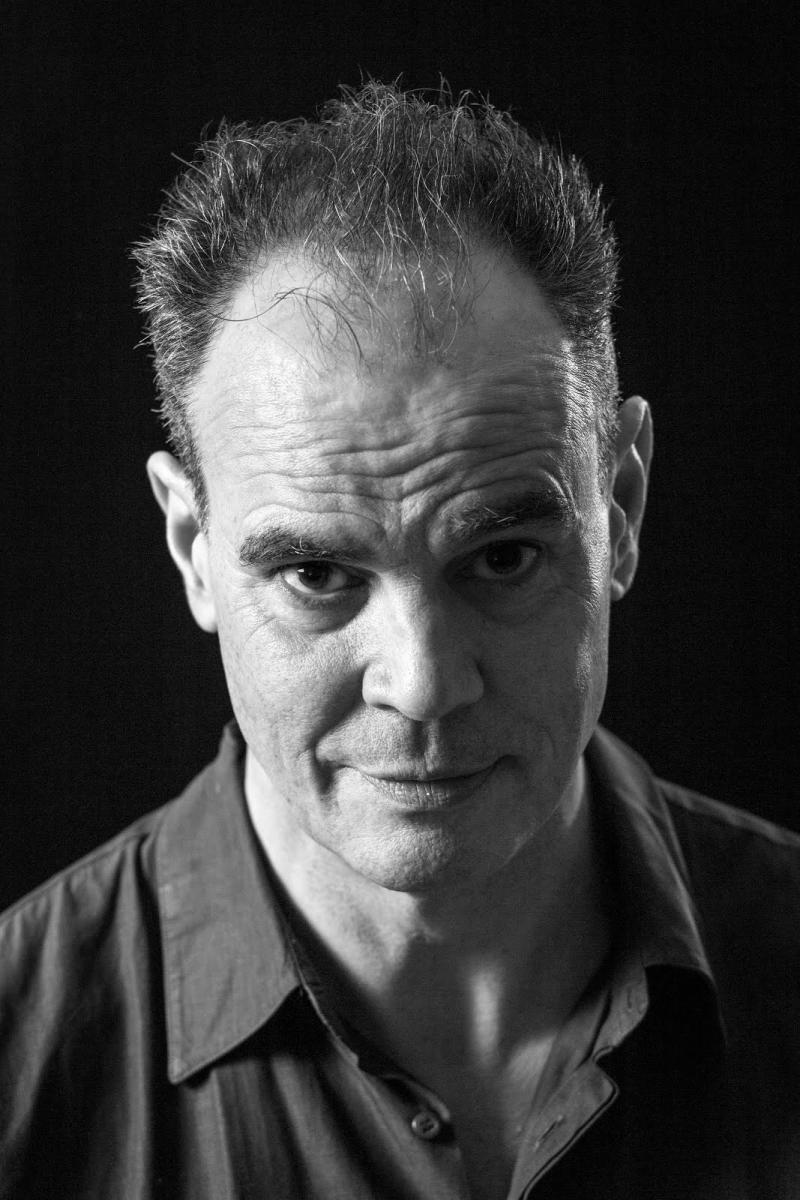

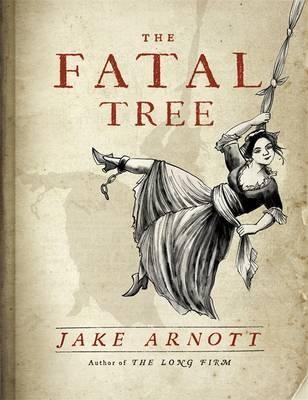

Novelist Jake Arnott has an eye for seedy glamour. The Fatal Tree takes the 1720s underworld - the setting of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, one of the most successful of all time - and adds more sex and a slick story, to make this rivetingly vivid tale.

The Fatal Tree is narrated alternately by prostitute Edgworth Bess (born Elizabeth Lyon), who speaks in dialect, and William Archer, a gay writer with a more neutral register. Bess’s vocabulary has been researched carefully, and Arnott includes a fascinating glossary of criminal slang, as well as a lengthy bibliography. The pair offer effectively complementary perspectives as narrators, though Bess’s voice very occasionally jars and clunks. Compared, say, to Peter Carey’s re-creation of period criminal dialect in True History of the Kelly Gang, her narrative has a few Google-translate moments of oddly mechanical syntax.

As in previous works, Arnott blends historical characters with fictional to good effect. Bess is historical, though little is known about her. Archer is made up, but details of his life are based on some historical gay writers of the period. Thief and gaol-breaker Jack Sheppard is, of course, much more familiar, and was treated by contemporary writers, most notably John Gay, whose character of Macheath in The Beggar’s Opera was based on him. Thief-taker (essentially a mob moss) Jonathan Wild is also well known.

Bess begins life serving an aristocratic family in Middlesex, but is expelled when the son of the house beguiles her into bed and she is blamed by the boy’s mother. Making her way to London, she immediately falls into the society of the Hundreds of Drury, a notorious home of thieves and prostitutes. Although both Bess’ seduction is similar to Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Tess and Bess are, psychologically, worlds apart. Conned of both her virginity and livelihood, Bess resolves without further ado to wreak revenge on the hypocritical gentry. As a narrator and guide, Bess is terrific company, full of lust, mischief and schemes, but her world view contains few spiritual depths, hidden or otherwise.

Bess begins life serving an aristocratic family in Middlesex, but is expelled when the son of the house beguiles her into bed and she is blamed by the boy’s mother. Making her way to London, she immediately falls into the society of the Hundreds of Drury, a notorious home of thieves and prostitutes. Although both Bess’ seduction is similar to Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Tess and Bess are, psychologically, worlds apart. Conned of both her virginity and livelihood, Bess resolves without further ado to wreak revenge on the hypocritical gentry. As a narrator and guide, Bess is terrific company, full of lust, mischief and schemes, but her world view contains few spiritual depths, hidden or otherwise.

Arnott fleshes out his tale’s historical context with bold, deft strokes, giving us just enough to make sense of the action without ever straying into history textbook territory. The South Sea Bubble is tumescent, Grub Street is a-buzz, and Daniel Defoe one of the most prized ghost-writers of the criminal autobiographical pamphlets widely sold at hangings. (He probably wrote the story of Sheppard’s life that Arnott has used here.) The poet John Gay patronises Archer - and was, after Defoe, one of the first professional authors to tell Sheppard’s story.

Arnott’s relationship with the mass-market end of gangster lit (and its cinematic twin, the Ritchie oeuvre and the like) is complex. Arnott’s fiction is scrupulous about telling otherwise neglected stories. He’s always drawn out the gay experience very evocatively, whether of the Krays and their milieu, as in his gangland trilogy, or later in the hinterland of glam-rock in Johnny Come Home. Here, the scenes in the molly houses are terrific, and the fate of gay men shocking: sodomy was a capital offence. Yet this is still, essentially, fiction in which narrative trumps artifice: pockets are picked, bodices ripped, and Bess’ colleagues hung (or killed by a disease they catch in prison) at (literally) breakneck pace. It works because Arnott does it so well. Entertainment is paramount, but is richly invested with fascinating historical detail. One wonders if he has his eye on cinematic adaptation. It would work a treat.

For readers of contemporary fiction, Arnott’s vigour, frankness and immediacy, in a historical setting, is very refreshing. In places The Fatal Tree is reminiscent of a more politically sensitive version of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels. From a literary-historical point of view, he is hasn’t so much created a new genre as blown the dust off the Newgate novel, a popular kind of sensational criminal fable in vogue in the early 19th Century, of which William Harrison Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard is a pre-eminent example. Rarely has such a delicious romp also felt so worthwhile.

- The Fatal Tree is published by Sceptre

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment