'Making it new' - Blake Morrison on adaptation, and how his new play came to life | reviews, news & interviews

'Making it new' - Blake Morrison on adaptation, and how his new play came to life

'Making it new' - Blake Morrison on adaptation, and how his new play came to life

The writer on working with Northern Broadsides on 'For Love or Money'

Is there anything more terrifying for a playwright than the first day of rehearsals? For months, even years, you’ve been working and reworking the text, saying the words aloud to yourself in an empty room and imagining the actors saying them to a packed auditorium.

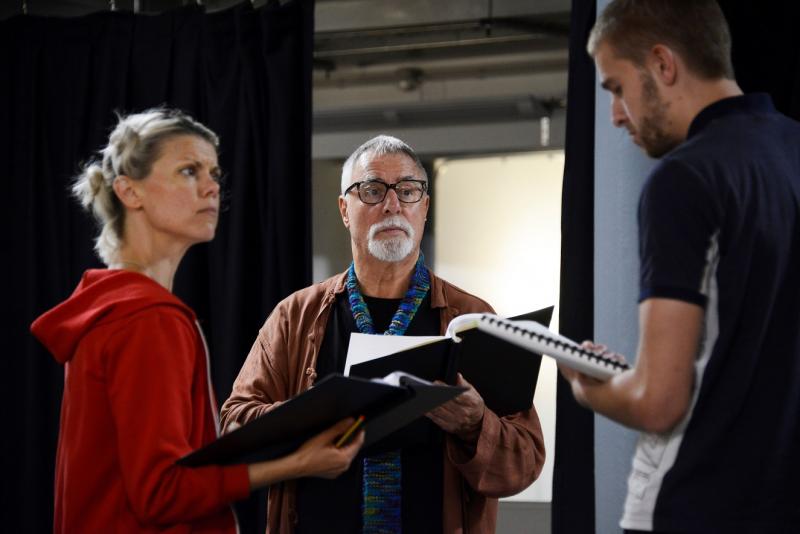

Of course, they’re probably paranoid as well, worrying whether you think they’re up to the job. And the director has plenty of worries too: about the wisdom of casting x as y, about the lack of rehearsal time, about the volume of advance booking for the show. It’s only when the read-through’s over, and the first few scenes are rehearsed, and people start getting to know each other, that everyone relaxes a little. Perhaps the play can be made to work, after all. Maybe audiences will even laugh at the jokes. (Blake Morrison, pictured below by Nobby Clark)

I wouldn’t describe myself as a playwright but since the mid-1990s I’ve adapted a number of classics for the theatre company Northern Broadsides, taking originals written in German, Italian, Russian and Ancient Greek (plus one, in Geordie, that required only minor adjustments) and rendering them into modern English – usually spoken with a Yorkshire accent. For all but one of those plays, the director has been Barrie Rutter, who set up the company; with several he has also taken the lead role. I know his values and I know how he works. Still, after 20-odd years I still find the first day of rehearsals an ordeal.

I wouldn’t describe myself as a playwright but since the mid-1990s I’ve adapted a number of classics for the theatre company Northern Broadsides, taking originals written in German, Italian, Russian and Ancient Greek (plus one, in Geordie, that required only minor adjustments) and rendering them into modern English – usually spoken with a Yorkshire accent. For all but one of those plays, the director has been Barrie Rutter, who set up the company; with several he has also taken the lead role. I know his values and I know how he works. Still, after 20-odd years I still find the first day of rehearsals an ordeal.

Our latest venture is For Love or Money, a version of a little-known French comedy by Alain-René Lesage, called Turcaret – a play so savage in its attack on corruption and greed in 18th-century Paris that the establishment tried to prevent it being staged (it came off after only seven performances). Barrie urged me to make it new and I’ve done so, with key roles – a chevalier, a marquis, a baronne and a so-called “tax farmer” – replaced by characters more likely to be found in a small Yorkshire town in the 1920s: a bank manager, a war widow, a doctor’s son and a sheep farmer. To set the play just ahead of the 1929 Crash felt right; setting it in the 1980s or '90s would have meant modern technology (computers, mobile phones, etc), which Barrie prefers to keep offstage. The plot remains much the same as the original, with everyone on the make and no redemption. But the comedy’s a little dafter, and the tone more burlesque than social-realist.

Rather than telling his cast what’s wanted, Barrie shows them - which facial expression to use, which gesture to adopt, which word to emphasise

Though I’ve watched Barrie directing many times, I never tire of it. Rather than telling his cast what’s wanted, he shows them – which facial expression to use, which gesture to adopt, which word to emphasise. “Watch your pronouns,” he’ll shout. “In real life we inflect naturally – it’s only actors who put the stress in the wrong place.” In the first week of rehearsals, he’ll use full sentences: “Remember to react – in a play none of the characters know what’s going to happen.” By the second week, it’s more a matter of slogans: “Stichomythia!”, “Machine-gun!”, “Dance the idea!”.

Some dramatists hand over perfectly formed texts and stay away from rehearsals. Others sit through every one, meddling and tinkering. I come somewhere in between. To start with, I’ll be there every day, cutting and rewriting as required: it’s important to stay flexible – you learn things about the characters once actors inhabit them. By weeks two and three, I’m less hands-on but there’ll still be an email every evening, asking could I add a sentence here (to help the timing of an exit, say) or avoid a repetition there. In week four I’m back for the dress rehearsal and first preview. Then it’s press night the week after. All scary, in their different ways, as is the next big moment, when the play moves to a different venue. For a touring company like Northern Broadsides, each new theatre brings a new challenge, whether the type of stage (proscenium arch, in the round, etc) or the age and expectations of the audience.

There’s a part of me that wants to be there for every performance. But I’ll ration myself to the first night in Halifax and the last in York, with the odd catch-up in-between. Any more I’d drive myself mad. It’s not as if a long run reduces the tension. The nerves are always there.

This will be Barrie’s last tour with Northern Broadsides: after 25 years, fed up of haggling for proper funding from the Arts Council, he’ll no longer be running the company. I’m sure he’ll continue acting and directing. But this could be our last collaboration. Which gives the play a poignant subtext – less a farce, more a tragi-comedy.

- For Love or Money opens September 15 at the Viaduct Theatre, Dean Clough, Halifax, then touring the UK to 2 December

- Read more First Person pieces on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Add comment