Jasper Johns, Royal Academy review - a master of 50 shades | reviews, news & interviews

Jasper Johns, Royal Academy review - a master of 50 shades

Jasper Johns, Royal Academy review - a master of 50 shades

'Something resembling truth': the master mark-maker transforms the familiar into the exotic

The Royal Academy has a winning line in spectacular exhibitions that have become essentials in London, theatrically and dramatically revelatory presentations in themselves. Here is another winner, the American star Jasper Johns, a collaboration with the world’s newest gallery of contemporary art, the Broad in Los Angeles.

Johns makes iconic objects from simple domestic items, from brooms and torches to the American flag (normally untouchable: in America’s officially secular society schoolchildren still swear an oath of allegiance to it). He even includes, as is perhaps inevitable, reproductions and riffs on other people’s art. He transforms everything that catches his gaze – and his imagination – into something else. Over 50 years ago he put it simply: “My idea has always been that in painting the way ideas are conveyed is through the way it looks and I see no way to avoid that.”

It is a subtle emphasis perhaps that art, all art in all media really, is about alchemy and metamorphosis, ideas – and feelings – into form. As the title of the RA show reminds us, Johns’ own credo appears to be, “One hopes for something resembling truth, some sense of life, even of grace, to flicker, at least, in the work.”

It is a subtle emphasis perhaps that art, all art in all media really, is about alchemy and metamorphosis, ideas – and feelings – into form. As the title of the RA show reminds us, Johns’ own credo appears to be, “One hopes for something resembling truth, some sense of life, even of grace, to flicker, at least, in the work.”

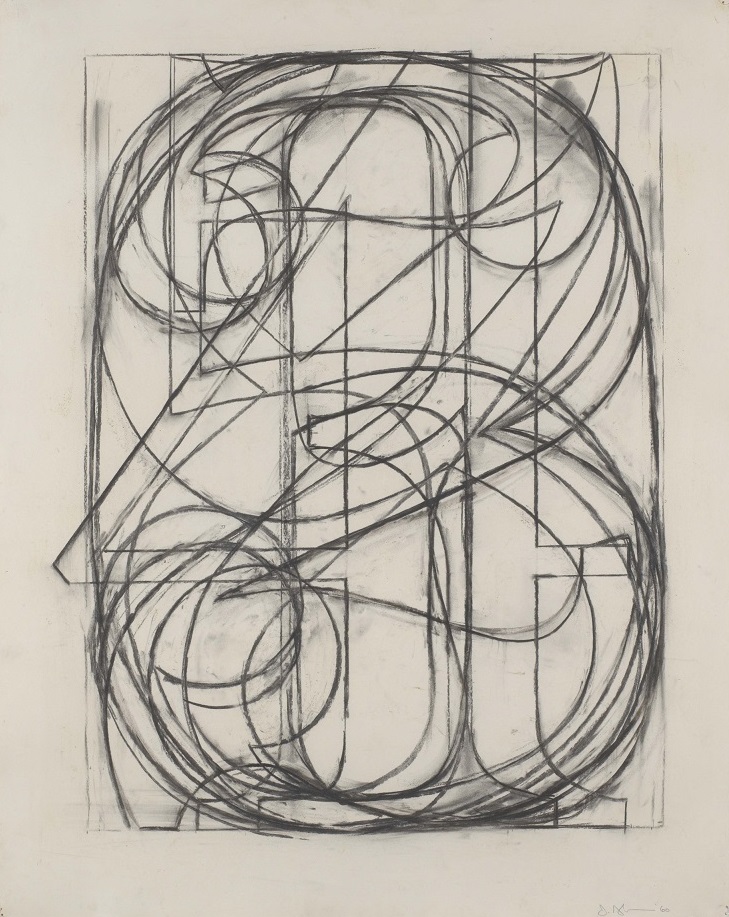

Seen in amplitude as it is here, his work seems unified by its overt commitment to language, both written and visual, particularly in its shorthand form of symbols and codes. In his own magical way, Johns has managed to turn the iconic into his own, and in particular is besotted by language in so many different forms. Here are letters, numbers, sign language, maps, targets, even anthologies of colour, and endless varieties of mark-making: hatching, doodling, stencilling, layering, thick impasto – smooth, delicate, seductive, encaustic (where pigment is contained in hot wax), you name it, he’s done it. He is obsessed with the building blocks of visual languages. And for all of his own verbal observations, he can be sardonically sarcastic about that process: The Critic Sees are drawings of spectacles, and where eyes might be there are mouths, a theme picked up on by the British pop artist Richard Hamilton.

All this and more is on view in the finest galleries Europe has to offer, the piano nobile of the Royal Academy, now with walls painted a matt silvery grey, a unified background that reminds us that Johns is as fine a colourist as he is anything else, painter, sculptor, printmaker or draughtsman. A marvellous huge blown-up photograph of the young Jasper Johns greets visitors at the entrance to this magical show: he sits, casually yet elegantly, on a stool in his studio, eyes half shut, wearing a huge smile.

The impression is one of excitement, exuberance, as though he cannot believe his luck; an adjacent trolley is heaped with tins of this and that, collections of brushes, the tools of the trade – and is that a Robert Rauschenberg work in progress on the wall? He is in his way a showman; not for nothing did he and Rauschenberg, friend, colleague and lover, support themselves when immigrants to New York – Johns from Georgia, Rauschenberg from Texas – doing window dressing for classy shops from Tiffany’s to Bonwit Teller. Handsome and fearsomely bright, these two young southerners soon fell in with the avant-garde, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and the best of all gallerists, Leo Castelli.

The impression is one of excitement, exuberance, as though he cannot believe his luck; an adjacent trolley is heaped with tins of this and that, collections of brushes, the tools of the trade – and is that a Robert Rauschenberg work in progress on the wall? He is in his way a showman; not for nothing did he and Rauschenberg, friend, colleague and lover, support themselves when immigrants to New York – Johns from Georgia, Rauschenberg from Texas – doing window dressing for classy shops from Tiffany’s to Bonwit Teller. Handsome and fearsomely bright, these two young southerners soon fell in with the avant-garde, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and the best of all gallerists, Leo Castelli.

The studio became his subject too, or rather its impedimenta: brooms, drink, paintbrushes, a coat hanger, a light bulb – in sculpture and wall-hanging conglomerations and paintings, just stuff (Fool’s House, 1961-62, Private Collection, pictured above left). But nevertheless emotive and suggestive of visitors, of domesticity, of nesting, of dust and light. There is throughout much of the work a sense of the gorgeousness of things, a surprising sumptuousness, a hint at seductive textures. The sensuality is emphasised in a small grey painting which has been literally bitten, and literally titled: Painting Bitten by a Man. He is certainly a master of 50 shades.

Johns publicly does not care about a public: “I make what it pleases me to make… no ideas about what the paintings imply about the world.” In that sense his packed surfaces leave plenty of room for us to make of things what we will. In one sense, Johns provides what westerners who have visited Japan often find there – something totally foreign, like the other side of the moon, yet inexplicably familiar – but with Johns something elusively beautiful is found in translation, rather than lost. It cannot be wholly accidental that in the earlier work, which will probably remain classic, Johns uses universal motifs. The majority of the American Flags on view are in fact historic: they have just 48 stars, completed before Alaska and Hawaii became states in 1959 (Flag, 1958, Private Collection, pictured above). Later Flags, whilst looking authentic and depicting the “real” flag in various colour ways, are playful and inaccurate. Johns does quietly joke, fooling us perhaps, and himself. On display too is Johns’ superb artist’s book, Foirades/Fizzles, a collaboration from 1976 with that other most elusive artist, the wordsmith Samuel Beckett. A perfect match between two people fixated by language in various forms.

It cannot be wholly accidental that in the earlier work, which will probably remain classic, Johns uses universal motifs. The majority of the American Flags on view are in fact historic: they have just 48 stars, completed before Alaska and Hawaii became states in 1959 (Flag, 1958, Private Collection, pictured above). Later Flags, whilst looking authentic and depicting the “real” flag in various colour ways, are playful and inaccurate. Johns does quietly joke, fooling us perhaps, and himself. On display too is Johns’ superb artist’s book, Foirades/Fizzles, a collaboration from 1976 with that other most elusive artist, the wordsmith Samuel Beckett. A perfect match between two people fixated by language in various forms.

Art feeds into art in a sequence of patterned paintings which play with the coloured hatchings of Edvard Munch’s late self-portrait masterpiece, Between the Clock and the Bed, in which the old Norwegian stands between those indications of mortality. Here, though, for Johns only the pattern is extracted and played with (Between the Clock and the Bed, 1981, Collection of the Artist, pictured below). Superimposing in many variations clear-cut letters and numbers, he also plays with visual expectations: irresistibly, like working out a puzzle, the eye tries to identify those so familiar signifiers 0 through to 9, or A to Z (pictured top right, 0 Through 9, 1960, Collection of the Artist). One double-sided bronze sculpture even plays with the specific gestures of sign language. Somehow the latest work has lost some of its zest and is curiously fatigued, mixing up older motifs, meandering through them in a kind of ramble. But that is a small blip in this wonderfully alluring compilation. What comes across in this massive but spacious show is the sheer beguiling physicality of the work. Up close and personal, Johns is a master mark-maker in whatever medium he chooses, transforming the familiar, often shockingly, into the exotic, ablaze with a meditative intelligence. Just go – and enjoy.

Somehow the latest work has lost some of its zest and is curiously fatigued, mixing up older motifs, meandering through them in a kind of ramble. But that is a small blip in this wonderfully alluring compilation. What comes across in this massive but spacious show is the sheer beguiling physicality of the work. Up close and personal, Johns is a master mark-maker in whatever medium he chooses, transforming the familiar, often shockingly, into the exotic, ablaze with a meditative intelligence. Just go – and enjoy.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment