From Life, Royal Academy review - perplexingly aimless | reviews, news & interviews

From Life, Royal Academy review - perplexingly aimless

From Life, Royal Academy review - perplexingly aimless

A lacklustre account of a defining practice in western art

Dedicated to a foundation stone of western artistic training, this exhibition attempts a celebratory note as the Royal Academy approaches its 250th anniversary.

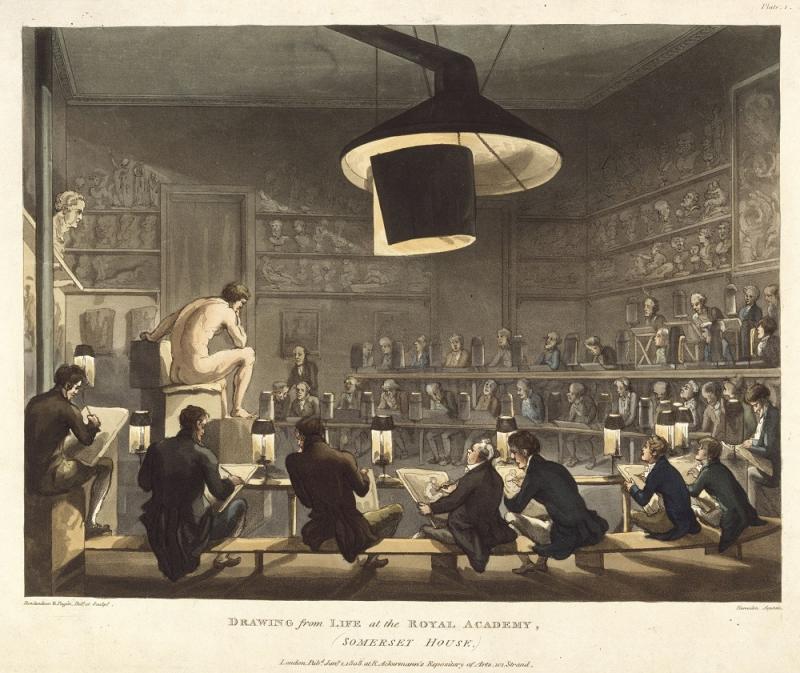

The study of nature was fundamental to Renaissance thinking, and as artists aspired to the naturalism they perceived in Antique sculpture, working from the life took on a new significance that endured, one way or another, into the 20th century. In the 18th century, as institutions like the Royal Academy replaced the system of apprenticing artists in workshops, the life room achieved quasi-sacred significance, access to which would only be granted after a lengthy period copying prints and casts of Ancient and Renaissance sculptures. It’s no coincidence that 19th century paintings and prints like Rowlandson’s Drawing from Life at the Royal Academy, 1808 (main picture), tend to show students in the life room, a setting that embodied the pinnacle of artistic training, the primacy of drawing and implicitly the learned status of artists conversant with precedents from the ancient and more recent past.

While the National Portrait Gallery’s recent exhibition The Encounter offered a nuanced assessment of drawing from life as the backbone of Renaissance workshop practice, the Royal Academy’s show lacks anything like its focus or insight. We never really get any sense of how working from life might practically or conceptually have shaped the output of early academicians, and we are reliant on several fine casts of classical sculptures from the Royal Academy’s collection to evoke something of their experiences (pictured right).

While the National Portrait Gallery’s recent exhibition The Encounter offered a nuanced assessment of drawing from life as the backbone of Renaissance workshop practice, the Royal Academy’s show lacks anything like its focus or insight. We never really get any sense of how working from life might practically or conceptually have shaped the output of early academicians, and we are reliant on several fine casts of classical sculptures from the Royal Academy’s collection to evoke something of their experiences (pictured right).

How artists from our own times have responded to the life receives slightly more productive attention, with Lucian Freud’s barely begun painting A Beginning, Blond Girl, 1980, perhaps the most fascinating piece in the whole show, showing a working method that seems entirely at odds with the appearance of Freud’s finished works. The figure is set out in the most ghostly and yet simultaneously, the most assured terms, with only a small section of the face having been worked up in detail. It’s a process that seems more sculptural than painterly, the modelling done inch by inch, with paint built up layer by layer in small and precise, but still confident strokes.

Life drawing had fallen out of fashion by the Seventies and Eighties, and Goldsmith’s College went so far as to ban it because it was felt to objectify women. Perhaps in light of this Jeremy Deller’s largely self-explanatory if still rather surprising project, the Iggy Pop Life Class, 2016, might be interpreted as demonstrating the irrepressible vigour of the life class, despite everything. In the end it’s hard to resist the very opposite conclusion which is that by making it the subject of an artwork, it becomes an ironic observation of a dying practice.

If the formal institution of the life class has lost ground, examples of work by Jenny Saville and Chantal Joffe attest to the continued importance of the female nude. They lack the force they deserve though, largely because the exhibition does nothing to address the overwhelmingly male character of the 19th and early 20th century life room, in which with few exceptions, women were only welcome as models. Consequently, the visceral treatment of the female body by women painters, and in Joffe’s case, her treatment of her own body, lacks the context needed to make any impact (pictured left: Chantal Joffe, Self Portrait with Hand on Hip, 2016).

If the formal institution of the life class has lost ground, examples of work by Jenny Saville and Chantal Joffe attest to the continued importance of the female nude. They lack the force they deserve though, largely because the exhibition does nothing to address the overwhelmingly male character of the 19th and early 20th century life room, in which with few exceptions, women were only welcome as models. Consequently, the visceral treatment of the female body by women painters, and in Joffe’s case, her treatment of her own body, lacks the context needed to make any impact (pictured left: Chantal Joffe, Self Portrait with Hand on Hip, 2016).

The real hobby horse of this exhibition is virtual reality, and Jonathan Yeo’s self-portrait sculpture, cast in collaboration with Google Arts & Culture, is the product of a strange mix of sculpture and painting – painting in three dimensions – made possible by Google’s Tilt Brush software. Elsewhere, the relationship between VR technologies and working from the life is more strained, with Farshid Moussavi’s architectural environment and Yinka Shonibare’s three-dimensional painting, offering a bizarre conclusion to an exhibition that never really quite got started.

- From Life at the Royal Academy until 11 March 2018

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment