Ballet's Dark Knight - Sir Kenneth MacMillan, BBC Four review – hagiography and home videos | reviews, news & interviews

Ballet's Dark Knight - Sir Kenneth MacMillan, BBC Four review – hagiography and home videos

Ballet's Dark Knight - Sir Kenneth MacMillan, BBC Four review – hagiography and home videos

Little is revealed about the enigmatic choreographer's life or why we should care about his legacy

If you came to this programme knowing nothing about the choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, you may have learned a few things. That he died, tragically and rather dramatically, of a massive heart attack during a first night performance of one his own ballets. That he was "interested" in sex and death, and frequently choreographed violent forms of both in his ballets.

For Ballet's Dark Knight was a programme that explained nothing where it could get away with murmured pieties or soft-focus solemnity instead, and it left the viewer knowing little more than they might have gleaned from Wikipedia. MacMillan could have come out of nowhere for all the programme contextualised the post-war ballet scene he entered as a young man, and might have done nothing except create works for the Royal Ballet for all it said about his legacy of psychological realism in choreography. The buzzwords "dark", "sex" and "death" were repeated enough for us to grasp that MacMillan was unusual in his appetite for showing these on stage, but how were viewers supposed to assess the originality of MacMillan's contribution without any sense whatsoever being given of the more "usual" ballet to which he stood in contrast?

For Ballet's Dark Knight was a programme that explained nothing where it could get away with murmured pieties or soft-focus solemnity instead, and it left the viewer knowing little more than they might have gleaned from Wikipedia. MacMillan could have come out of nowhere for all the programme contextualised the post-war ballet scene he entered as a young man, and might have done nothing except create works for the Royal Ballet for all it said about his legacy of psychological realism in choreography. The buzzwords "dark", "sex" and "death" were repeated enough for us to grasp that MacMillan was unusual in his appetite for showing these on stage, but how were viewers supposed to assess the originality of MacMillan's contribution without any sense whatsoever being given of the more "usual" ballet to which he stood in contrast?

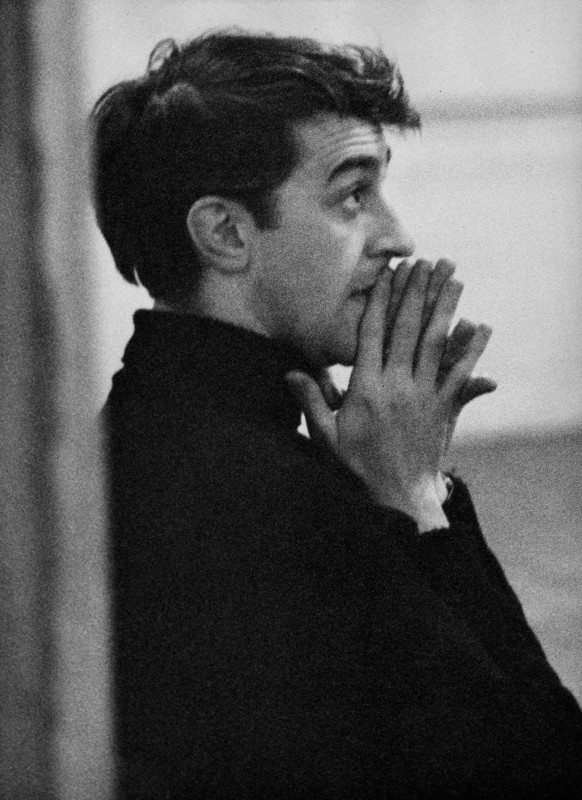

The defence will be, perhaps, that this was supposed to be a character portrait, an intimate look at his soul and its many dark nights. Certainly the programme is stronger on that ground: as the cameras linger on various black and white photos of MacMillan's rather melancholic face, contemporaries including his wife and daughter amply explain his grounds for unhappiness – starting from a shell-shocked father, a beloved mother and sister dying young, and lifelong struggles with anxiety, depression and an often hostile artistic milieu. The home movies which form the much-vaunted new footage are quietly poignant: despite MacMillan's evident deep devotion to his little daughter and beautiful wife, he has a look of contained sadness that never really lifts. But there is little in the way of real psychological insight here; the most tantalising moment comes in passing, close to the end, when it is revealed that he had an insatiable passion for buying costume jewellery, most of which was never looked at or worn.  A character portrait is only worthwhile if we care about the character involved, and – plain human sympathy aside – Dark Knight couldn't really articulate why we ought to care about Kenneth MacMillan. His choreography as seen on film, even de-historicised and de-contextualised, is much the strongest argument in his favour, and there is some good stuff here: Lynn Seymour in The Invitation, Sylvie Guillem as Manon, Tamara Rojo as Juliet, a teenage Darcey Bussell rehearsing The Prince of the Pagodas, and Viviana Durante in Mayerling. For the ballet fan however, these glimpses satisfy only because they speak to a much richer contextual knowledge of the ballets involved. The rape scene in The Invitation is spot-on in its depiction of brutality, for example, but even more hard-hitting if one knows the full ballet, which unflinchingly portrays both asymmetrical sexual power dynamics and the nasty veneer of "polite" society that perpetuates them and covers them up (pictured above, Francesca Hayward and Gary Avis in a recent production of The Invitation at the Royal Ballet). For the non-ballet fan I imagine these choreographic excerpts are enigmatic, mere tantalising glimpses that leave one wanting to know more.

A character portrait is only worthwhile if we care about the character involved, and – plain human sympathy aside – Dark Knight couldn't really articulate why we ought to care about Kenneth MacMillan. His choreography as seen on film, even de-historicised and de-contextualised, is much the strongest argument in his favour, and there is some good stuff here: Lynn Seymour in The Invitation, Sylvie Guillem as Manon, Tamara Rojo as Juliet, a teenage Darcey Bussell rehearsing The Prince of the Pagodas, and Viviana Durante in Mayerling. For the ballet fan however, these glimpses satisfy only because they speak to a much richer contextual knowledge of the ballets involved. The rape scene in The Invitation is spot-on in its depiction of brutality, for example, but even more hard-hitting if one knows the full ballet, which unflinchingly portrays both asymmetrical sexual power dynamics and the nasty veneer of "polite" society that perpetuates them and covers them up (pictured above, Francesca Hayward and Gary Avis in a recent production of The Invitation at the Royal Ballet). For the non-ballet fan I imagine these choreographic excerpts are enigmatic, mere tantalising glimpses that leave one wanting to know more.

The BBC really should have considered screening an entire MacMillan ballet alongside this programme, not only to satisfy the curiosity piqued by the excerpts but because it would have done a much better job of explaining what he was about than a series of respectful talking heads, however heartfelt their memories. Dancers can be notoriously bad at putting into words the great ranges of subtlety and meaning they can access with their bodies, and one certainly would have learned more from watching Monica Mason or Darcey Bussell either in performance or in rehearsal than from their rather stilted talking pieces direct to camera.

Deborah MacMillan, Kenneth's widow, sharp and frank, gives better TV. But if the most interesting contribution to a documentary about a genuinely significant artist comes from his wife, that is hardly to the production team's credit. Jann Parry, author of an acclaimed MacMillan biography, lives in London – her omission looks like either (inexcusable) laziness or deliberate dumbing down. Was there not a single other dance historian or scholar who could have been interviewed about MacMillan's context and legacy?

Kenneth MacMillan, in his best work, made an astonishing success both of conveying complicated emotion and of exploding classical narrative ballet's seriously rigid formal constraints. He himself was convinced he was an outsider, but has been crowned by history as one of the most influential figures there has ever been in British dance. He was not least – as ballet critic Clement Crisp points out – a superb craftsman, and he worked incredibly hard for his success. For all those reasons, he deserved a better documentary than this.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment