McQueen review - the dark brilliance of Alexander McQueen | reviews, news & interviews

McQueen review - the dark brilliance of Alexander McQueen

McQueen review - the dark brilliance of Alexander McQueen

Moving documentary charts the anarchic fashion designer's life and career

Lee Alexander McQueen said that he pulled the horrors out of his soul and put them on the catwalk. Eight years after his death, and three years after the record-breaking Savage Beauty retrospectives at the Metropolitan Museum and the V&A, his extraordinary story remains as powerful as ever.

Full of archive footage, it’s a chance to see those stunning catwalk shows as well as new interviews with assistants, friends, models and family, some of whom haven't talked before (others, like Bobby Hillson, who brought McQueen on to her Central St Martin's MA fashion course, and former assistant and boyfriend Andrew Groves, were on the 2011 McQueen and I TV doc). It starts at the beginning, when Lee McQueen was a pudgy, unprepossessing lad in Stratford, the youngest of six children, son of a taxi driver who didn’t like queers. He wasn’t much good at school but he was always drawing clothes in lessons.

The film is presented in five chapters, or tapes, named after the shows that were his most pivotal. The first is his 1992 MA graduation show (his aunt Renee provided the money for the course), “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims”, providing a taste of what was to come – the runway as performance art, the gothic and historical elements, the danger, the darkness. Some of the clothes were blood-red inside and lined with human hair, like a body. (He was already an accomplished pattern-cutter, having been apprenticed at 16 to Savile Row tailors Anderson & Sheppard – his mum’s idea). Stylist Isabella Blow, McQueen’s eccentric muse and friend, bought the whole collection, in stages. He would march her to the cashpoint.

The film is presented in five chapters, or tapes, named after the shows that were his most pivotal. The first is his 1992 MA graduation show (his aunt Renee provided the money for the course), “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims”, providing a taste of what was to come – the runway as performance art, the gothic and historical elements, the danger, the darkness. Some of the clothes were blood-red inside and lined with human hair, like a body. (He was already an accomplished pattern-cutter, having been apprenticed at 16 to Savile Row tailors Anderson & Sheppard – his mum’s idea). Stylist Isabella Blow, McQueen’s eccentric muse and friend, bought the whole collection, in stages. He would march her to the cashpoint.

Their relationship was intense; she was like a mother or sister, says McQueen’s older sister Janet (her son Gary, who worked for McQueen as a designer, convinced Janet to participate in the film). It was Blow's idea for him to use his middle name because it sounded more marketable. She and McQueen fell out later after he was appointed to Givenchy and didn’t give her the role she expected, even though she had a hand in brokering the deal. This isn’t fully explored, as we mainly get former husband Detmar Blow’s side of the story (he does like to talk), though you can understand that appointing an extravagant muse might not be appealing to a couture house's bottom line. McQueen never commented publicly: she killed herself by drinking weedkiller in 2007, after several other suicide attempts, underlining the uneasy parallel between their lives.

His charisma was astonishing. “We were paying him to work for him,” remembers his friend and agent Alice Smith. There was hardly enough money for a pint of milk at first and he used his dole money to buy fabric, but Blow’s high-fashion connections propelled him into the right places.

He was convinced the world was against him, that Paris was waiting to see him crash

Fame, with all its craziness, came fast. “Highland Rape”, in 1995, had shock value. It was based on the Highland Clearances of the 18th century, with torn dresses – models looked like they'd been violated – and low-cut tartan bumsters (he said he wanted models to put their pubic hair in Anna Wintour’s face). It referred to his Scottish heritage, on which he was fixated, and to Janet being abused by her violent ex-husband – a man who’d also sexually abused McQueen as a child, which had a profound effect on his life and work.

Another show featured a pile of crashed cars that caught fire by mistake, but everyone carried on, of course. At another the model's dress was spray-painted by robots – his assistants always hoped fervently that he would “forget about the robots”, but they remained a theme. Michael Nyman’s beautiful score adds to the drama (they were friends, and McQueen would play his music late into the night at his studio. He also, in early days, listened constantly to Sinéad O'Connor on his Walkman.)

Everything changed with the Givenchy role. “The money was good,” says McQueen. But the chandeliers, the stuffy grandness of the Parisian atelier (he was the first designer to allow the Givenchy tailors to enter the hallowed area), the way they treated him like a king when he didn’t want to behave like one – it was, he said, like taking a dinosaur out of the sea. McQueen and his wild London entourage were seen as street-urchins. And he missed his dogs. “The fun times were over,” says designer and former assistant Sebastian Pons. McQueen slimmed down, thanks to liposuction and lots of cocaine. He was convinced the world was against him, that Paris was waiting to see him crash. John Galliano at Dior had four times his budget, he thought. “Paranoia will destroy her,” was one of his maxims. He heard voices, became aggressive, trusted no one, especially not his boyfriends. Sometimes he was super-cool, says Pons, sometimes “he was “like a devil crossing the door. It was hellish.”

Everything changed with the Givenchy role. “The money was good,” says McQueen. But the chandeliers, the stuffy grandness of the Parisian atelier (he was the first designer to allow the Givenchy tailors to enter the hallowed area), the way they treated him like a king when he didn’t want to behave like one – it was, he said, like taking a dinosaur out of the sea. McQueen and his wild London entourage were seen as street-urchins. And he missed his dogs. “The fun times were over,” says designer and former assistant Sebastian Pons. McQueen slimmed down, thanks to liposuction and lots of cocaine. He was convinced the world was against him, that Paris was waiting to see him crash. John Galliano at Dior had four times his budget, he thought. “Paranoia will destroy her,” was one of his maxims. He heard voices, became aggressive, trusted no one, especially not his boyfriends. Sometimes he was super-cool, says Pons, sometimes “he was “like a devil crossing the door. It was hellish.”

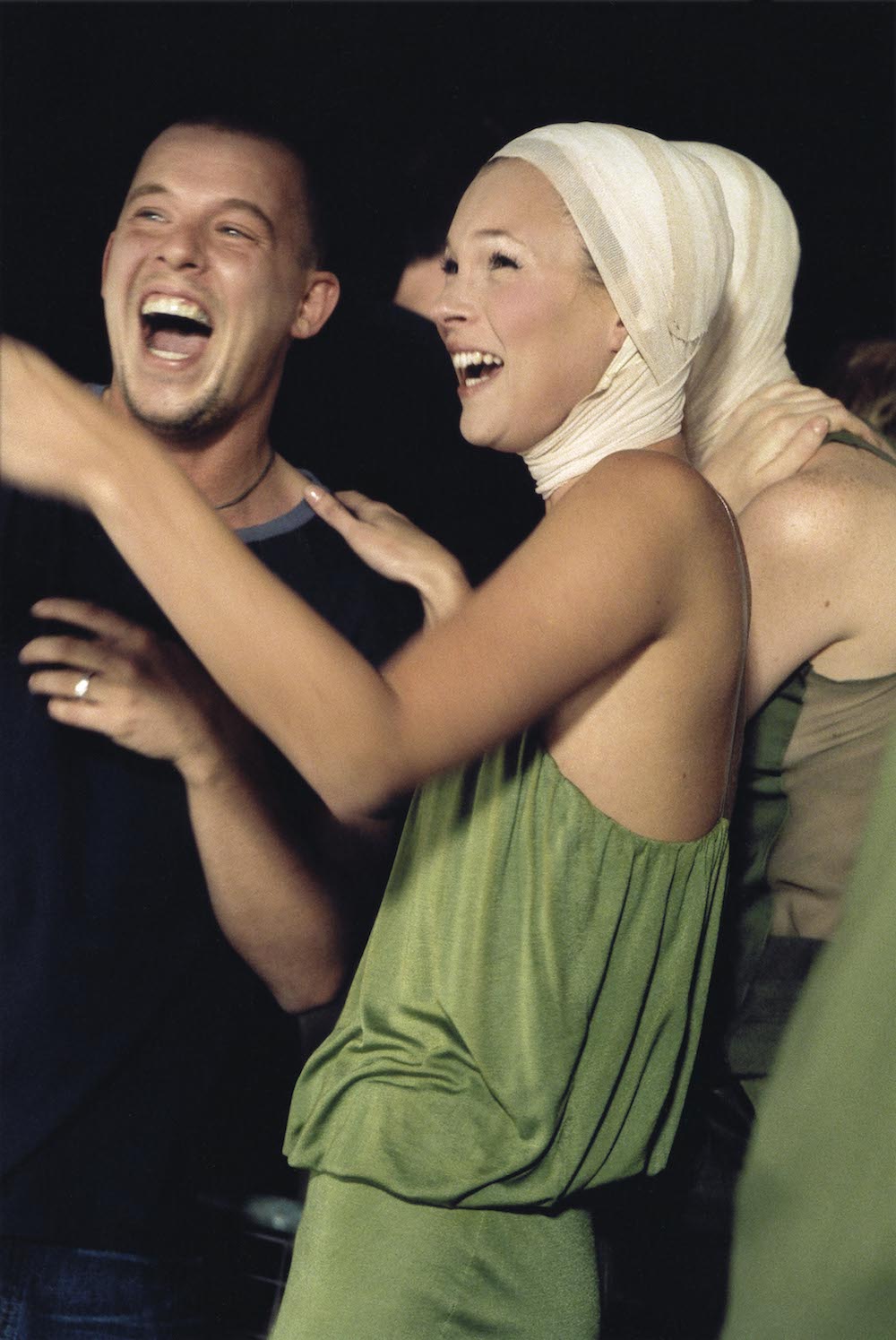

In “Voss” (2001) fetishism and lunacy shine forth. Models with bandaged heads (McQueen wth Kate Moss, pictured above left; he loved his friend and stylist Mira Chai-Hyde’s post-surgery look) are trapped in a mirrored box like a padded cell in a mental hospital, unable to see the audience. At the end, a box within the box flaps open to reveal a large naked woman in a mask, breathing through a tube, surrounded by fluttering moths. “Fat birds and moths – fashion’s worst nightmare,” says Michelle Olley, the bird in question. No arguing with that.

McQueen seemed trapped as well. He had become a global brand, doing 14 collections a year. He was HIV positive and wanted to escape the constant pressure. “I can’t just stop,” he told friends, “fifty people have to pay their mortgages.” He planned to kill himself as part of his final show, the triumphant “Plato’s Atlantis” in 2009, but was dissuaded. Less than a year later, he hanged himself in his wardrobe on the night before his mother’s funeral. He was 40. “We can all be discarded quite easily,” said McQueen in an interview. “You’re there, then you’re gone.” In his case, not so fast.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

Add comment