Prom 40, Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Bell review - tea-time treats with wit and dash | reviews, news & interviews

Prom 40, Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Bell review - tea-time treats with wit and dash

Prom 40, Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Bell review - tea-time treats with wit and dash

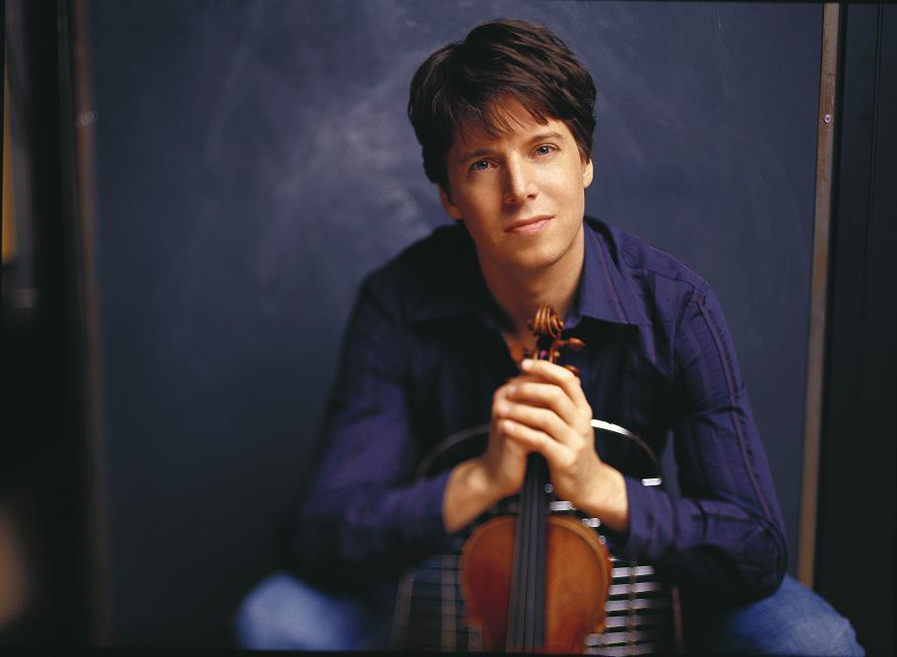

Who needs a conductor with a leader-soloist of this calibre?

When did this weird mix-tape fashion take root at the Proms?

Yes, smart programming draws attention to the hidden kinship that binds seemingly disparate pieces across periods and styles. Still (literally, in this case) – do give us a break. An outfit as taut, lithe and exhilarating as the ASMF and their ever-youthful American director have no need of stunts. This Sunday afternoon concert, packed with families, could have offered little more than a pleasant easy-listening stroll in (or at least beside) the park. But Bell, who directs his tight-knit and bright-toned 40-strong forces from the leader’s desk, generated an excitement that banished any hints of tea-time torpor. Other Proms this season may offer more in the way in innovation and transformation. But the spirit and style of Bell and his band made this a feel-good session to prove that musicians of this quality can delight a crowd without patronising populism.

Few in the hall, I’m confident in claiming, would have missed a conductor. Following in founder Sir Neville Marriner’s big but always nimble shoes, Bell has led the ASMF since 2011. It takes a long, close rapport with an ensemble to sound as briskly coherent and responsive as they do without a specialist stick-wielder up front. For Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, the Bridge and the Beethoven, Bell played as leader while – when the orchestration allowed – simultaneously wielding the bow of his Stradivarius as a baton. Periodically, it reared up like a rampant unicorn or a submarine periscope, calling out across the stage to guide woods or brass. As standing soloist in Saint-Saëns’s Third Violin Concerto, Bell would face the audience for his star turns, but then twist or swerve around to lead the band. If all this movement sounds like hyper-active distraction, then the evidence of the ears argued that no one had lost their concentration.  The Academy makes up in agility what it potentially lacks in weight. The fairy strings of Mendelssohn bounced and skittered, the dreamlike woodwinds of the opening chords felt suitably otherworldly, while Bottom’s braying tuba-ass sounded droll but not crude. This teenager’s jeu d’esprit (the prodigy was 17) revels in elegant inventiveness as well as ripe jokes. The ASMF embraced its sophistication. Saint-Saëns’s concerto, written in 1880 for the Spanish celebrity virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate, also abounds in a tuneful charm that might, in the wrong hands, cloy. Bell’s were emphatically not the wrong hands. He never permitted this work’s honeyed lyricism to turn to mush. The B minor melancholy of the first movement intimates that we’re not just here for a soupy Romantic wallow (Elgar’s own violin concerto sometimes comes to mind). Bell kept the mood mellow but not sluggish.

The Academy makes up in agility what it potentially lacks in weight. The fairy strings of Mendelssohn bounced and skittered, the dreamlike woodwinds of the opening chords felt suitably otherworldly, while Bottom’s braying tuba-ass sounded droll but not crude. This teenager’s jeu d’esprit (the prodigy was 17) revels in elegant inventiveness as well as ripe jokes. The ASMF embraced its sophistication. Saint-Saëns’s concerto, written in 1880 for the Spanish celebrity virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate, also abounds in a tuneful charm that might, in the wrong hands, cloy. Bell’s were emphatically not the wrong hands. He never permitted this work’s honeyed lyricism to turn to mush. The B minor melancholy of the first movement intimates that we’re not just here for a soupy Romantic wallow (Elgar’s own violin concerto sometimes comes to mind). Bell kept the mood mellow but not sluggish.

His energetic pirouettes between orchestra and audience paid dividends in the lovely middle-movement barcarolle: an andantino that depends on a give-and-take dialogue between violin and orchestra – especially woodwinds. Bell’s sensitivity to his fellow-players gave it grace as well as lusciousness; a touch of strangeness, too, as the bittersweet song dissolves into disconcerting arpeggios. Saint-Saëns in this vein needs art as much as heart, and Bell commanded both. The final tarantella lent him scope for some especially swashbuckling moves, while his playing never seemed to lose finesse. This movement’s stately chorale theme hints at a more Brahms-like gravitas, with the trombones of the Academy adding both heft and sheen to its closing return among the brass. For all his panache, Bell as soloist allowed his colleagues to shine too; a refreshing display of togetherness.

Written to commemorate the drowning of his friends’ daughter after a German U-boat sank the liner Lusitania in 1915, Bridge’s brief, sombre Lament opened the second half. I’m not sure that this placing of an introspective miniature before (mostly) sunlit and cheerful Beethoven succeeded, even if Bell wished to argue for a similarity by folding one work into another. But the Lament did turn some well-deserved limelight towards Bell’s string colleagues (viola and cello above all). Then, after that deceptive, disturbing false door of the adagio, the clouds lifted over Beethoven’s Fourth. The ASMF swung through this comparatively carefree symphony with a genial drive that nonetheless took care to preserve clarity of outline and vividness of colour. In the adagio, above all, we heard the sheer individuality of the voices – clarinet and flute in particular – that the ASMF style cherishes and foregrounds. Bell and colleagues made a thoroughly persuasive case for Beethoven stripped not only of a baton-wielding dictator, but massive firepower as well.

True, the sprightly, Haydn-esque Fourth favours their approach (I would love to hear their Eroica), but modesty of size never meant timidity of sound. The joky stop-start surges, retreats and repetitions in the scherzo had a fizzing sense of surprise. In the shimmering perpetual motion of the finale, again, pace made room for clarity – with delicious bassoons to the fore. With Mendelssohn’s Shakespearean fantasia, we had begun with smart and witty musical comedy – in the deepest sense. We ended in the same manner. Bell seeded plenty of exuberance among his co-workers, but of a collegiate, democratic kind. This formidable partnership needs no cult of personality to thrive. Long may it endure.

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

BBC Proms: Le Concert Spirituel, Niquet review - super-sized polyphonic rarities

Monumental works don't quite make for monumental sounds in the Royal Albert Hall

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Frang, Romaniw, Liverman, LSO, Pappano, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - sunlight, salt spray, Sea Symphony

Full force of the midday sea in the Usher Hall, thanks to the best captain at the helm

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

Elschenbroich, Grynyuk / Fibonacci Quartet, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mahogany Brahms and explosive Janáček

String partnerships demonstrate brilliant listening as well as first rate playing

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

BBC Proms: Akhmetshina, LPO, Gardner review - liquid luxuries

First-class service on an ocean-going programme

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Budapest Festival Orchestra, Iván Fischer, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - mania and menuets

The Hungarians bring dance music to Edinburgh, but Fischer’s pastiche falls flat

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Classical CDs: Hamlet, harps and haiku

Epic romantic symphonies, unaccompanied choral music and a bold string quartet's response to rising sea levels

Comments

The 'weird mix-tape fashion'

The 'weird mix-tape fashion' has been around, fitfully, for many years. I remember Ligeti segueing into Tchaikovsky at a Prom conducted by Thomas Dausgaard, and Ligeti segueing into Strauss in one from Jonathan Nott. And I love it, usually - it sheds new light on both works in question. More, please!