Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to Cézanne review - much loved treasures, seen afresh | reviews, news & interviews

Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to Cézanne review - much loved treasures, seen afresh

Courtauld Impressionists: From Manet to Cézanne review - much loved treasures, seen afresh

Favourite paintings from the Courtauld Gallery reveal the collector's eye

Heir to one of this country's great textile manufacturing firms, Samuel Courtauld (1876-1947) – highly original in his then unfashionable fascination with the art of his own lifetime – bought some of the best known and best loved paintings now in the public domain.

The Courtauld’s current home, the late 18th century Somerset House, has never been wholly comfortable with the physical adaptations needed to fit it for a 21st century teaching institution and art gallery. Currently undergoing its third renovation, the art gallery’s closure has provided the excuse for this totally dazzling exhibition at the National Gallery, uniting the bequest of impressionist and post-impressionist art from Courtauld’s own collection with a selection from those his financial bequest (£50,000) to the National Gallery itself helped towards purchasing.

All these masterpieces, large and small, are well known, so what is the purpose of bringing them together in this way? By making this excellent display, the viewer begins to understand the collector’s eye, and the lasting consequences of enlightened philanthropy which ensures there is not a monopoly of taste: we think of the National Gallery as a government supported museum, of course, but its foundation was by gift and the highest part of its holdings are gifts and bequests.

By joining these two aspects of Courtauld’s support for impressionist and post-impressionist painting only a handful of decades after its making, we have, displayed with heart-breaking clarity, a snapshot of the period. Courtauld did most of his collecting in only four years, between 1926-1930, but had earlier committed purchasing funds to the National Gallery. We are reminded that the National Gallery refused to buy a Monet as late as 1905. Moreover, a trustee refused the offer in 1915 by the enlightened collector Hugh Lane (whose bequest is now shared by Dublin and London) to show work from this period at the gallery, saying that he would as “soon expect to hear of a Mormon service being conducted in St Paul’s Cathedral, as to see an exhibition of the modern French Art-rebels in the sacred precincts of Trafalgar Square.”

By joining these two aspects of Courtauld’s support for impressionist and post-impressionist painting only a handful of decades after its making, we have, displayed with heart-breaking clarity, a snapshot of the period. Courtauld did most of his collecting in only four years, between 1926-1930, but had earlier committed purchasing funds to the National Gallery. We are reminded that the National Gallery refused to buy a Monet as late as 1905. Moreover, a trustee refused the offer in 1915 by the enlightened collector Hugh Lane (whose bequest is now shared by Dublin and London) to show work from this period at the gallery, saying that he would as “soon expect to hear of a Mormon service being conducted in St Paul’s Cathedral, as to see an exhibition of the modern French Art-rebels in the sacred precincts of Trafalgar Square.”

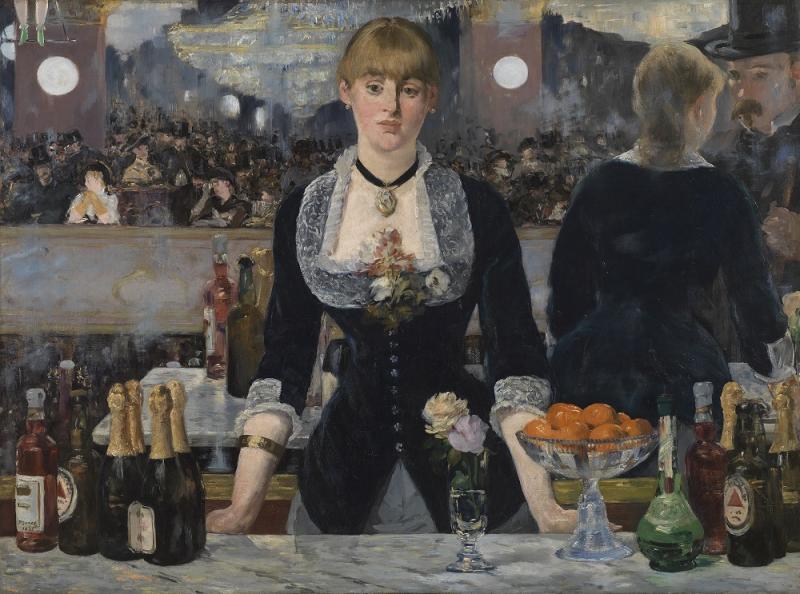

Now masterpieces from the Hugh Lane bequest of 1917 are on show with the Courtauld impressionists, for example the highly complex and captivating crowd scene depicted in mesmerising miniature, Manet’s Music in the Tuileries Gardens, 1862. Displayed next to it are Manet’s smaller version of Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1862-63, one of the most famous and notorious compositions in all art history, albeit based on a Raphael composition, and the astonishing Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, (main picture) which convincingly breaks all the rules of perspective, teasing us with mirrored reflections.

The contents of this selective jewel box is almost overwhelming, so take your time to slowly savour. In the next gallery, take a breath for five small Degas, which show his humane range of poetic yet curiously realistic portraits; the monumental Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884, factory chimneys belching smoke in the far distance, framing the working classes at leisure by the river. Toulouse-Lautrec and Renoir lead us on to perhaps the toughest room, the compositions still so unexpected and commanding, the colour so subtle, dark yet luminous. Nine Cézannes, feature some of his favourite subjects: card players, still lifes centred on studio objects and fruits, provençal landscapes, a self portrait.

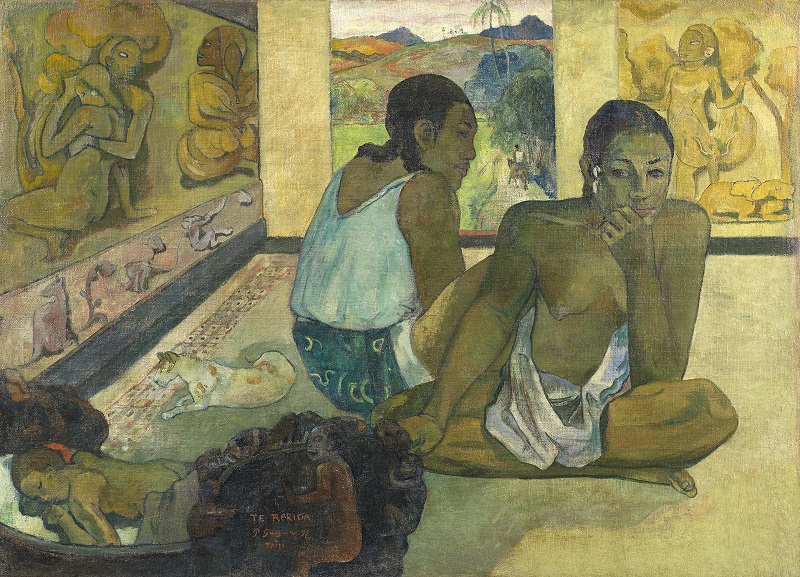

And on to further revelations ending with a flourish: two Gauguins from his soujourn in the South Pacific, Nevermore, 1897, showing his Tahitian mistress, and his Te Rerioa, 1897 (Pictured above), with its mysterious figures of two women, a child – and a cat. These are set against a Gauguin at home done several years before, The Haystacks, 1889, depicting harvest in Brittany.

And of course there is also Daumier, Pissarro, Monet, Bonnard, not to mention the powerfully rhythmic Van Gogh’s A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (Pictured above), painted in the summer of 1889, a scene from the landscape around Saint-Rémy, where he had voluntarily gone to live in an asylum in the penultimate year of his short life. It is a painting, seemingly pastoral, which somehow indicates perfectly the turbulent intelligence of this extraordinary group of intertwined artists, friends and rivals. It was bought by the National Gallery with the Courtauld Fund in 1923.

And of course there is also Daumier, Pissarro, Monet, Bonnard, not to mention the powerfully rhythmic Van Gogh’s A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (Pictured above), painted in the summer of 1889, a scene from the landscape around Saint-Rémy, where he had voluntarily gone to live in an asylum in the penultimate year of his short life. It is a painting, seemingly pastoral, which somehow indicates perfectly the turbulent intelligence of this extraordinary group of intertwined artists, friends and rivals. It was bought by the National Gallery with the Courtauld Fund in 1923.

This selective sampling of over 40 paintings, with 26 coming from the Courtauld galleries, puts into sharp focus the astonishing achievement of these painters who somehow convinced us as well as themselves to see the observed world in new and enlightening ways.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious