Klimt/Schiele, Royal Academy review - the line of gauntness | reviews, news & interviews

Klimt/Schiele, Royal Academy review - the line of gauntness

Klimt/Schiele, Royal Academy review - the line of gauntness

Elegance and brutality converge in drawings from the Albertina Museum, Vienna

The most touching tribute to the relationship between two giants of early 20th century art, Gustav Klimt and the much younger Egon Schiele, hangs in the first room of this fascinating exhibition at the Royal Academy – Schiele’s poster for the 49th Secessionist exhibition in 1918.

Schiele was blown away when he first encountered Klimt’s work, years before he actually met the artist. Perpetually broke and scouting for society patrons, he once tried billing himself as “the silver Klimt” – no gold leaf, and very much cheaper.

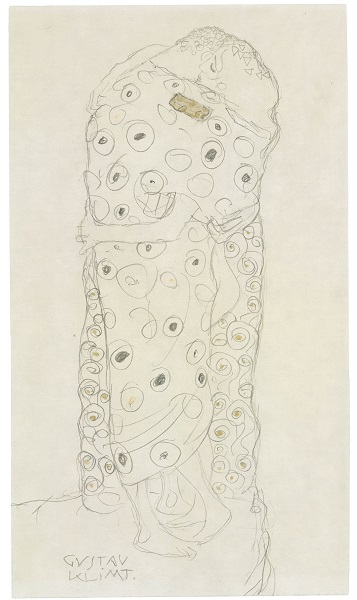

Klimt was not just richer but far more famous in their day, but he does not come well out of the contest in this exhibition of 100 drawings loaned by the Albertina. These are not the images for which he is most famous, the extraordinary Viennese society portraits of figures half dissolving into gold and jewels as if only their own wealth is keeping them vertical. Most of the works here, beautiful though they are, are working drawings in which he is trying out compositions – a rare finished work, probably made for presentation to a patron, also has the only tiny patch of gold in the entire collection (Pictured right: Klimt, Standing Lovers, 1907-8).

Klimt was not just richer but far more famous in their day, but he does not come well out of the contest in this exhibition of 100 drawings loaned by the Albertina. These are not the images for which he is most famous, the extraordinary Viennese society portraits of figures half dissolving into gold and jewels as if only their own wealth is keeping them vertical. Most of the works here, beautiful though they are, are working drawings in which he is trying out compositions – a rare finished work, probably made for presentation to a patron, also has the only tiny patch of gold in the entire collection (Pictured right: Klimt, Standing Lovers, 1907-8).

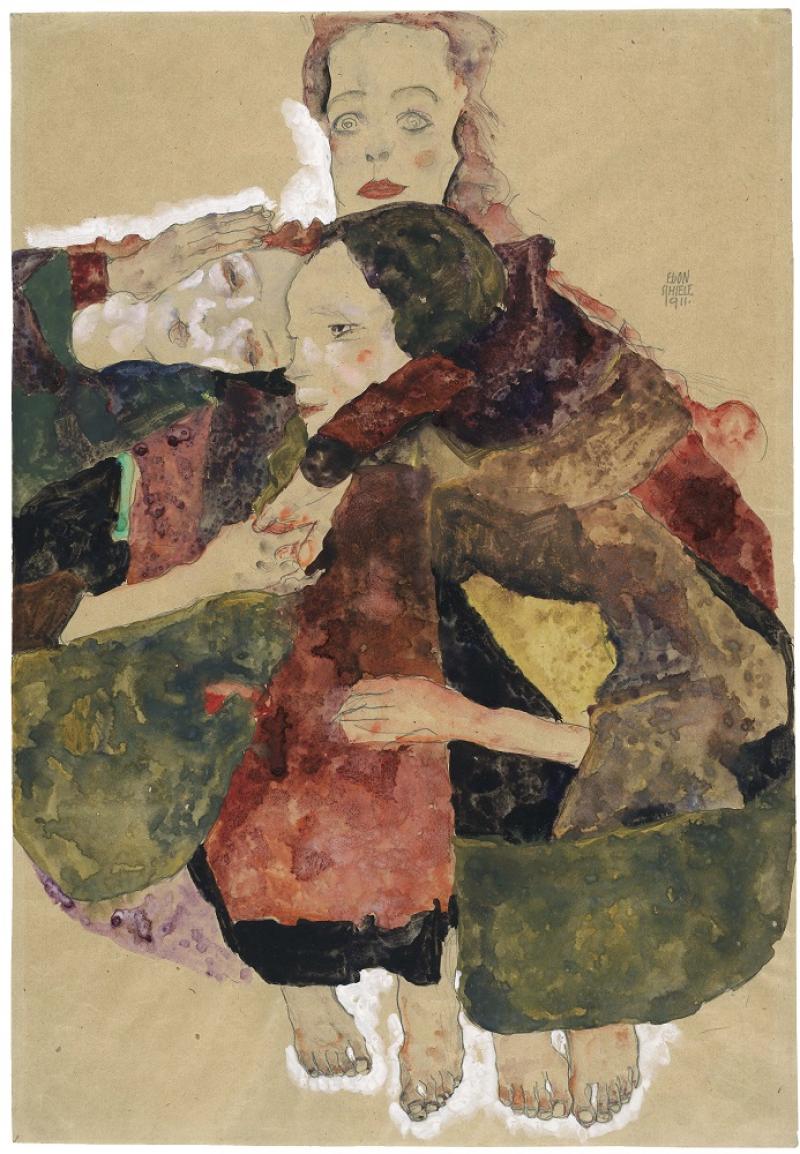

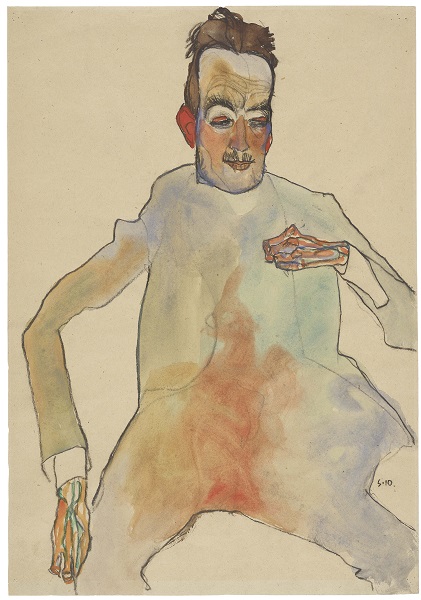

The Schiele works are complete, and once he shakes off some of the Klimt influenced excessive elegance, they are astonishing. The subjects are brutally viewed, brutally executed with a savage spareness, and brutally cropped so arms vanish at the elbow, legs mid shin. The poses must have been excruciating. Colour can be a weapon: a cellist’s arms are empty and instead of a musical instrument there is a great amber stain spreading up from his groin (Pictured below left: Schiele, The Cellist, 1910). The nudes are less disturbing than many in which the garments – including a self-portrait with a dangerous shirt – seem to be assaulting them, hobbling their legs, binding their arms, threatening to strangle them. In contrast the Klimt drawings of smartly dressed women hanging nearby could be fashion plates for a magazine.

The most striking of the Klimts are his working drawings and preparatory sketches for an important commission for the university. It ended badly when his allegory of medicine, a waterfall of naked figures, child and adult, hale and mortally ill, was not well received. He was outraged and tried to cancel the contract and take back the paintings.

The most striking of the Klimts are his working drawings and preparatory sketches for an important commission for the university. It ended badly when his allegory of medicine, a waterfall of naked figures, child and adult, hale and mortally ill, was not well received. He was outraged and tried to cancel the contract and take back the paintings.

Again the contrast with the greatest troubles of his protégé is telling. Schiele’s unarguably sexualised drawings of very young girls disturbed his contemporaries and have troubled his biographers since: the exhibition is at pains to point out that the age of consent at the time was 14. It was never likely to go well when he moved with his lover and model from urbane but expensive Vienna to a country village. He was arrested for child abduction of one of his child models, and though cleared of that, convicted of exposing minors to obscene works – which were confiscated, with the judge very publicly burning one.

The five prison drawings exhibited, including a self-portrait with just an anguished face peering from the tangle of his grey prison blanket, were made when he thought he might spend the rest of his life in prison.

The RA exhibition design seems intended to damp down excessive excitement. All the drawings are hung on porridge coloured walls into which some, particularly Klimt’s studies of masturbating women drawn in cobweb fine lines, almost sink without trace. The effect is to throw Schiele’s hectic points of colour, the crimson lips, nipples and groins, the green and pink flesh tones which sometimes recall medieval images of plague victims, into alarmingly sharp relief – and to make many of the elegant Klimt drawings shrink back into mere prettiness.

- Klimt/Schiele Drawings from the Albertina, at the Royal Academy until 3 February 2019

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name