Modern Couples, Barbican review - an absurdly ambitious survey of artist lovers | reviews, news & interviews

Modern Couples, Barbican review - an absurdly ambitious survey of artist lovers

Modern Couples, Barbican review - an absurdly ambitious survey of artist lovers

Exhibition revises the notion of the artist as lone genius, but reveals little else

What an ambitious project! Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde looks at over 40 couples or, in some cases, trios whose love galvanised them into creative activity either individually or in collaboration.

The best thing about the exhibition is that it blows out of the water the traditional notion of the artist as a lone (male) genius who draws inspiration from a supportive but essentially non-creative muse, usually his lover. At last, the role of women as essential partners in many creative relationships is being acknowledged and explored.

A typical example is that of Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto, who is world famous for his furniture designs as well as his buildings. No mention is usually made of his wife, Aino, who worked alongside him and was a founding member and director of Artek, the company they set up in 1935 to market the furniture, to design interiors for their own and other people’s buildings, and to run a design shop and art gallery in Helsinki. Aino played a crucial role in every aspect of the creative and business sides of the practice, yet her husband routinely took the credit. This was the norm rather than the exception, of course, a model that has been repeated ad nauseam.

The exhibition opens with the sad story of Camille Claudel, the young sculptor who, in 1882, became Rodin’s student, model and lover. “I express in a loud voice what all artists think,” Rodin exclaimed. “Desire! Desire! What a formidable stimulant.” It was a stimulant he used over and over again. The presence of his longterm partner, Rose Beuret, did nothing to deter him from having numerous affairs with young women, who often modelled for him.

The exhibition opens with the sad story of Camille Claudel, the young sculptor who, in 1882, became Rodin’s student, model and lover. “I express in a loud voice what all artists think,” Rodin exclaimed. “Desire! Desire! What a formidable stimulant.” It was a stimulant he used over and over again. The presence of his longterm partner, Rose Beuret, did nothing to deter him from having numerous affairs with young women, who often modelled for him.

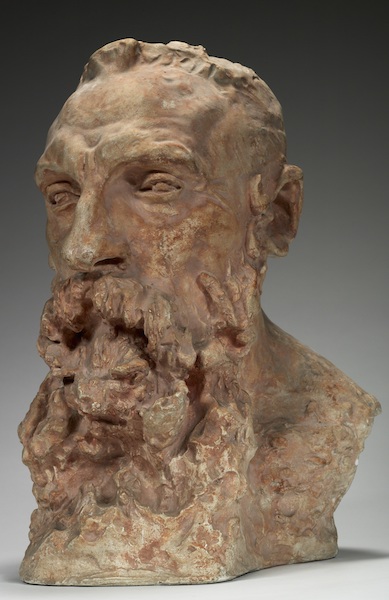

The relationship between the 42-year-old sculptor (pictured right: Portrait of Rodin 1888-1889 by Camille Claudel) and the 18-year-old Claudel developed into something much more than an affair, though. Soon she became indispensable to him as his advisor, collaborator and studio manager as well as his model and muse. “It took our encounter for everything to take on an unfamiliar life; my drab existence went up in flames of joy,” he wrote to her after she had finally left him: she could no longer bear his infidelities.

He went on to become world famous, inspired by his affairs with other young women including the painter Gwen John. Claudel, on the other hand, never recovered from their ten-year relationship. Despite her considerable talent, she failed to forge a career as a sculptor and eventually suffered a nervous breakdown and was incarcerated in a mental hospital until her death, 30 years later, in 1943.

Max Ernst was another serial philanderer. When he met the 19-year-old painter Leonora Carrington in 1937, he had already had affairs with artists Meret Oppenheim and Leonor Fini. He and Carrington were separated during the war, so he married Peggy Guggenheim only to leave her for the painter, Dorothea Tanning (pictured below: Rapture, 1944, by Dorothea Tanning). The exhibition catalogues one disastrous relationship after another. The women usually suffered the most, partly because of the emotional damage wrought by the break-up, but also because, until recently, it was virtually impossible for a woman to gain respect as an artist in a male-dominated world, so they underwent a double rejection.

The exhibition catalogues one disastrous relationship after another. The women usually suffered the most, partly because of the emotional damage wrought by the break-up, but also because, until recently, it was virtually impossible for a woman to gain respect as an artist in a male-dominated world, so they underwent a double rejection.

Russian artist Alexander Rodchenko was amazed by the cavalier attitudes towards women that he witnessed in France. “Only a man is a person, but women aren’t people,” he wrote from Paris. “You can do whatever you want with them.” By contrast, women in revolutionary Russia were able to thrive alongside their male colleagues and some mutually beneficial relationships were created. Rodchenko and his wife Varvara Stepanova, for instance, abandoned paint on canvas for media they considered more relevant to post-revolutionary times – photography and graphic design for him, theatre, textile and costume design for her.

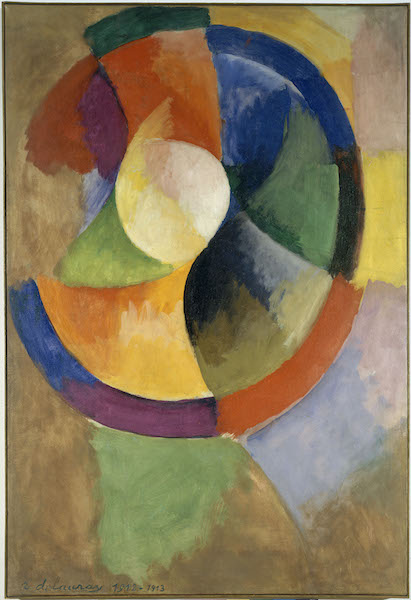

The Russian painters Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov also enjoyed a long and stable relationship. They lived and worked together for 60 years, early on developing a form of painting they called Rayonism, yet each produced a remarkably distinctive body of work. Sonia and Robert Delaunay stayed together from 1909 until his death in 1941 (pictured left: Formes circulaires, Soleil no 2, 1912-1913 by Robert Delaunay). She is given more space than he, mainly for the superb textile designs with which she supported the household; but, with only one painting included, you might wrongly assume that she was primarily a business woman rather than a first-rate abstract painter.

The Russian painters Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov also enjoyed a long and stable relationship. They lived and worked together for 60 years, early on developing a form of painting they called Rayonism, yet each produced a remarkably distinctive body of work. Sonia and Robert Delaunay stayed together from 1909 until his death in 1941 (pictured left: Formes circulaires, Soleil no 2, 1912-1913 by Robert Delaunay). She is given more space than he, mainly for the superb textile designs with which she supported the household; but, with only one painting included, you might wrongly assume that she was primarily a business woman rather than a first-rate abstract painter.

Basically, the remit of the show is too ambitious for it to work. Most of the chosen couples merit an exhibition of their own, but because so many are included there is space only for a few works each. This neither allows one to determine how much influence each exerted over the other nor, in the case of partnerships, who made what contribution. I would love to see a detailed analysis of the Delaunay’s work, for instance, to determine whose ideas were the main driving force.

Long texts introduce each couple and explain their work, and so the show really functions as a book on the walls. The result is an exhausting and rather overwhelming experience. The work of the Surrealists is displayed in an incomprehensible jumble, for instance, probably because the emotional entanglements they indulged in were too complex and often too fleeting to fathom.

I went to the exhibition anticipating that, at last, the role of women artists would be recognised and celebrated. Instead, I was made aware of how often powerful men have exploited younger women with impunity, and when a creative partnership was made up of equals, it tended to implode under its own intensity. Take Wassily Kandinsky and Gabrielle Münter, for example. They spent six years in Munich and the nearby village of Murnau, where they were joined by their Russian friends Marianne von Werefkin and Alexej von Jawlensky. Together in this idyllic setting, they developed a radical form of brightly coloured abstraction. Yet both men later chose to leave their artist partners for far less challenging relationships. Jawlensky married the maid and Kandinsky opted for a more conventional bourgeois marriage. At the Bauhaus, where he later taught, he was nicknamed "Herr Gott"; perhaps he needed a wife who also considered him a God.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name