Sonia Delaunay, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Sonia Delaunay, Tate Modern

Sonia Delaunay, Tate Modern

Eclipsed by her painter husband, the artist is finally receiving full recognition

In 1967 when she produced Syncopated Rhythm (main picture), Sonia Delaunay was 82; far from any decline in energy or ambition, the abstract painting shows her in a relaxed and playful mood. Known as The Black Snake for the sinuous black and white curves dominating the left hand side, this huge, two and a half metre wide canvas is deliciously varied.

This exhilarating display of confidence must surely have been a response to the fact that, finally, she was getting the recognition she deserved. Married in 1910 to the French painter Robert Delaunay, Sonia was regarded for most of her career as little more than his supporter and helpmate. After his death in 1941, though, she continued to produce ambitious paintings as well as designs for books, mosaics, rugs and furniture. And people gradually began to take notice. But it took a retrospective in Germany in 1958 and another in Paris, at the Musée National d’Art Moderne, the same year she painted Syncopated Rhythm, to achieve a fundamental shift in attitude.

Her contribution to French painting in the crucial early years of the century was at last being acknowledged and she was also being celebrated as an important role model for younger women. In the 1920s, Delaunay had run a thriving fashion house designing dresses, coats, accessories, swimwear and fabrics and, ironically, the very thing that prompted the art world to overlook her as a mere decorator now made her seem particularly relevant and interesting.

Her contribution to French painting in the crucial early years of the century was at last being acknowledged and she was also being celebrated as an important role model for younger women. In the 1920s, Delaunay had run a thriving fashion house designing dresses, coats, accessories, swimwear and fabrics and, ironically, the very thing that prompted the art world to overlook her as a mere decorator now made her seem particularly relevant and interesting.

Sonia Delaunay is normally thought of in relation to the French avant-garde – as a successor to Gauguin and Van Gogh; but wandering round Tate Modern’s hugely impressive retrospective of her work, what struck me was just how Russian she remained. Born in Odessa, she was adopted by a wealthy uncle in St Petersburg, where she lived among intellectuals, learned numerous languages and regularly travelled abroad. Before moving to Paris she studied art in Karlsruhe and, by the time she met Robert, was already exhibiting powerful paintings like Yellow Nude, 1908, (pictured above right). With its angular shapes, fierce colour contrasts and gloomy intensity, the picture suggests the influence of German Expressionists like Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner who used colour to create jarring dissonances. And in their bright colours, her mask-like portraits of young girls are strikingly similar to those being produced in Munich at the time by the Russian artist Alexej von Jawlensky, inspired by Russian folk art.

Her background had a profound impact in another, more important way. Wassily Kandinsky, that famous pioneer of abstract art, recalled visiting a Russian peasant’s home where every surface was painted with bright patterns so that life and art blended in one harmonious whole. While the encounter propelled him towards abstraction and the quest for a total work of art, similar cultural roots prompted Delaunay to make no distinction between fine and applied art. After the birth of her son Charles in 1911, she made a patchwork quilt for his cradle and then set about transforming the family home into a work of art with her hand-made cushions, lampshades, curtains, wall hangings and painted objects.

Her background had a profound impact in another, more important way. Wassily Kandinsky, that famous pioneer of abstract art, recalled visiting a Russian peasant’s home where every surface was painted with bright patterns so that life and art blended in one harmonious whole. While the encounter propelled him towards abstraction and the quest for a total work of art, similar cultural roots prompted Delaunay to make no distinction between fine and applied art. After the birth of her son Charles in 1911, she made a patchwork quilt for his cradle and then set about transforming the family home into a work of art with her hand-made cushions, lampshades, curtains, wall hangings and painted objects.

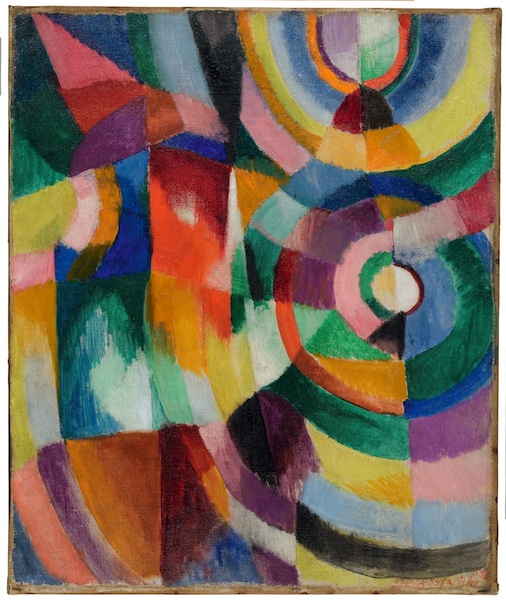

Meanwhile a tango craze was sweeping Paris and she and Robert began frequenting the Bal Bullier wearing garments collaged with fabrics that turned them into artworks. Back home she painted ambitious canvases celebrating the rhythms, speed and excitement of city life (pictured above left Electric Prisms, 1913). Inspired by the Italian Futurists’ infatuation with modern technology and urban living and by the chemist Michel-Eugene Chevreul’s discovery that colours are intensified by juxtaposition with their complementaries, the Delaunays began developing Simultaneity, an abstract language dominated by syncopated rhythms and contrasting colours, which they continued to explore for the rest of their lives.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 put paid to the income Sonia received from a property in St Petersburg. The couple were broke and Sonia was forced to make a living from design. She not only embraced the situation with gusto, but by the 1920s had become so successful that she employed a team of Russian women to knit, sew and embroider her designs. Under the brand name Simultané, she produced clothing and accessories for celebrities like Gloria Swanson (pictured right: Swanson's embroidered coat, 1924), Nancy Cunard and the architect Ernö Goldfinger. She furnished lavish apartments for the smart set and painted their cars, while also designing crazy costumes for avant-garde films and Dadaist performances. Her fabric designs for stores like Liberty’s and Metz & Co are endlessly inventive; squiggles, swirls, zig-zags, diamonds, stripes, fins, chevrons, spirals, squares, hyphens and blobs bring every surface to life. She was obviously having a ball; but then came the economic crash of 1929 and she had to close the business and return to painting.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 put paid to the income Sonia received from a property in St Petersburg. The couple were broke and Sonia was forced to make a living from design. She not only embraced the situation with gusto, but by the 1920s had become so successful that she employed a team of Russian women to knit, sew and embroider her designs. Under the brand name Simultané, she produced clothing and accessories for celebrities like Gloria Swanson (pictured right: Swanson's embroidered coat, 1924), Nancy Cunard and the architect Ernö Goldfinger. She furnished lavish apartments for the smart set and painted their cars, while also designing crazy costumes for avant-garde films and Dadaist performances. Her fabric designs for stores like Liberty’s and Metz & Co are endlessly inventive; squiggles, swirls, zig-zags, diamonds, stripes, fins, chevrons, spirals, squares, hyphens and blobs bring every surface to life. She was obviously having a ball; but then came the economic crash of 1929 and she had to close the business and return to painting.

She could, it seems, rise to any challenge. One room is devoted to three huge murals that she produced for the Paris Exhibition of 1937, a celebration of science and technology intended to boost international trade. Designed for the Palace of the Air, a hanger-like building celebrating aviation, the images are clear, simple and direct. With its circular dials, the Dashboard is recognisable as a Delaunay design, but the Propellor (pictured below) and Aeroplane Engine could have been conceived by Leger, Picabia or even Marcel Duchamp.

After Robert’s death, Sonia devoted considerable energy to securing his place in history, judiciously donating 47 of his works to the Musée National d’Art Moderne along with 67 of her own. Perversely, this move consigned her to history along with her husband and it would be several years before she was recognised as a living, breathing and active presence. During this period her paintings contain large areas of black and feel somewhat turgid and heavy; it's as though, determined that Simultaneity should be taken seriously, she is weighed down by the burden of responsibility. But the gouaches, a medium in which she evidently felt free to experiment, still have a wonderful freshness and vitality.

After Robert’s death, Sonia devoted considerable energy to securing his place in history, judiciously donating 47 of his works to the Musée National d’Art Moderne along with 67 of her own. Perversely, this move consigned her to history along with her husband and it would be several years before she was recognised as a living, breathing and active presence. During this period her paintings contain large areas of black and feel somewhat turgid and heavy; it's as though, determined that Simultaneity should be taken seriously, she is weighed down by the burden of responsibility. But the gouaches, a medium in which she evidently felt free to experiment, still have a wonderful freshness and vitality.

The last room of the exhibition is a delight. In Endless Rhythm, Dance, 1964, a cluster of circles gyrate around a spine of black arcs, while a paired-down version of the idea produces a strikingly beautiful rug. The overlapping squares and slender rectangles of Rhythm Colour, 1967, are extremely rich in density, handling and colour, while a similar freedom of touch makes the graphite scribbles and limpid colours of the etching suite Avec Moi-meme,1970, alive with incident.

During this final decade, Delaunay seems to be revisiting her own and Robert’s achievements and celebrating each one with the same relish and commitment that she brought to every phase of her creative life. What a trooper!

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment