The Unknown Soldier, Infra, Symphony in C, Royal Ballet, review - WWI ballet honours obscure tragedy | reviews, news & interviews

The Unknown Soldier, Infra, Symphony in C, Royal Ballet, review - WWI ballet honours obscure tragedy

The Unknown Soldier, Infra, Symphony in C, Royal Ballet, review - WWI ballet honours obscure tragedy

The storyline goes missing, presumed dead, in this Armistice commission

Pity fatigue is a risk for any artwork marking the anniversary of the 1918 Armistice. There can’t have been a man or woman in the Royal Opera House on Tuesday night who hadn’t already read, watched, or otherwise had their fill of the horrors of the Western Front and the never-ending debate over the futility of it all.

The Unknown Soldier, a collaboration between choreographer Alastair Marriott, designer Es Devlin and composer Dario Marianelli (Darkest Hour, Atonement), at least ploughed a new furrow by looking at two real-life individuals, 18-year-old conscript Ted Feltham and his sweetheart Florence Billington, whose testimony to those times, delivered in a quavering voice after a lapse of eight decades, is preserved on the film which opens the ballet.

But to feel another’s personal tragedy, you have to get to know them. And this ballet needed more time to deliver any more on Ted and Florence than the basics: that they met at a dance (cue Romeo and Juliet moment when they first lock eyes), and had barely got past their first kiss before he was marched off to the Front, never to return. Theirs is a story that has a beginning and an end but no middle. Tragic in itself, but in terms of dramatic arc, a dud. Yet there is beauty in this bookend of a spectacle. Overhung by a huge screen showing archive footage of the obsequies for the Unknown Soldier, whose anonymous corpse stood in for the tens of thousands deprived of proper burial, the opening set piece for men in khaki sets the tone. And if the fluid and luxuriant solo danced by Matthew Ball (as Ted, pictured above with Tomas Mock) said anything at all, it was that youth, strength and vitality are commodities too precious to be squandered. Solo trumpet melodies carry a whiff of the Last Post throughout. The musical influences extend to Prokofiev, too, in the pas de deux that Ted and Florence (a beautifully pliant Yasmine Naghdi) dance when they finally find each other at the local hop. This is a full-on tribute to the balcony duet from Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, but none the worse for that in its smoothly accomplished lifts and calibrated emotional build-up. It’s a tribute to Marriott’s craft and will make a fine stand-alone piece for galas when the rest of this ballet is mothballed.

Yet there is beauty in this bookend of a spectacle. Overhung by a huge screen showing archive footage of the obsequies for the Unknown Soldier, whose anonymous corpse stood in for the tens of thousands deprived of proper burial, the opening set piece for men in khaki sets the tone. And if the fluid and luxuriant solo danced by Matthew Ball (as Ted, pictured above with Tomas Mock) said anything at all, it was that youth, strength and vitality are commodities too precious to be squandered. Solo trumpet melodies carry a whiff of the Last Post throughout. The musical influences extend to Prokofiev, too, in the pas de deux that Ted and Florence (a beautifully pliant Yasmine Naghdi) dance when they finally find each other at the local hop. This is a full-on tribute to the balcony duet from Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, but none the worse for that in its smoothly accomplished lifts and calibrated emotional build-up. It’s a tribute to Marriott’s craft and will make a fine stand-alone piece for galas when the rest of this ballet is mothballed.

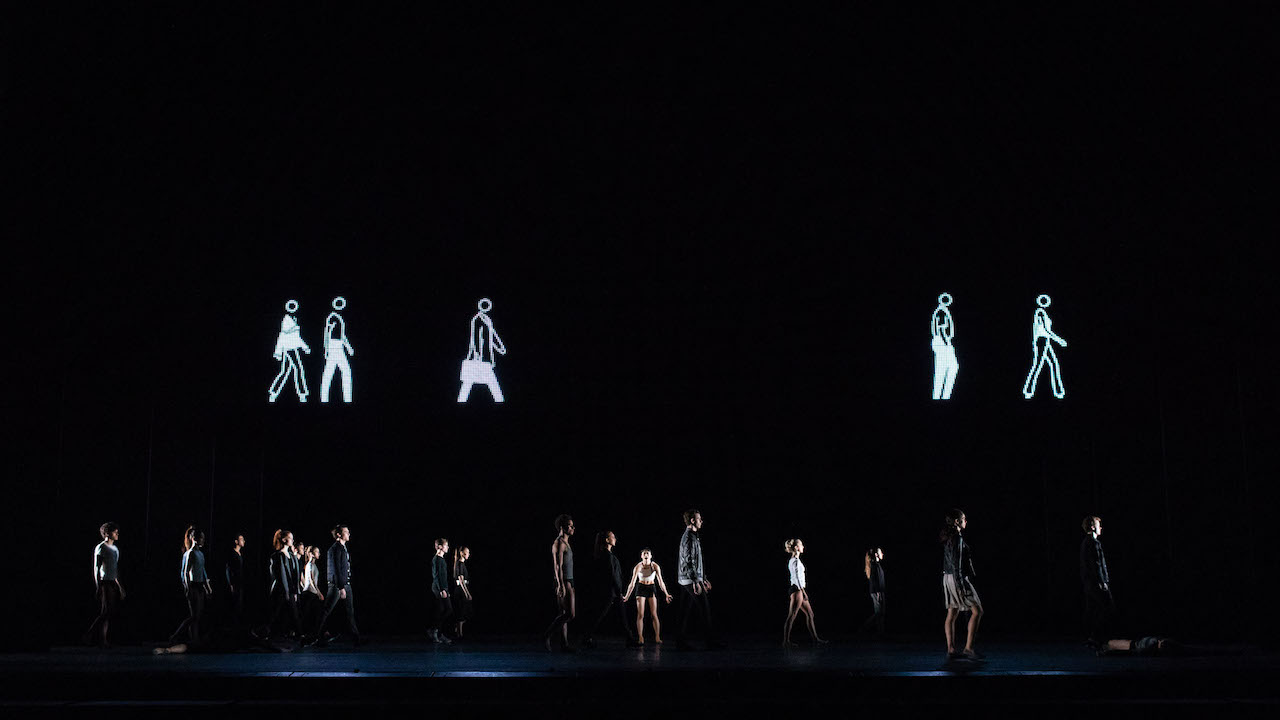

There is fun, too, in the preceding social dances as couples canter around a church hall to Marianelli’s lively approximation of Edwardian pop, the impression of crowded gaiety amplified by glancing shadows (lighting: Bruno Poet). But the abrupt curtailing of the love story – Ted is dead at the Front, and we don’t see how he died – is wholly unsatisfactory in a way that nothing – neither a scene with the arrival of the telegraph boy, showing Florence receiving the news, nor the recollections of a 106-year-old veteran, nor a post-mortem scene of naked youths bathed in golden light – can recover from. It’s a book with missing pages. Oddly, the emotional arc feels more complete in Infra, the Wayne MacGregor piece that follows. I say oddly, because MacGregor is not known for emotional content, and in this work, made in 2008, half of the people we see on stage are walking holograms with circles for heads (pictured above). On a virtual walkway over the real dancer's heads march a mesmerising trail of luminous pin figures, courtesy of the artist Julian Opie. Some carry shopping or a briefcase, but they are faceless, oblivious, relentless. Below them, flesh-and-blood figures engage in tense couplings. Partners divide and form new pairs, each demanding an attention you can't give it as they grapple in a line at the front of the stage. The defining moment comes as one girl, left alone, kneels distressed centre-stage as a rush-hour load of real-life people surge past her. On and on they come – it seems as if we’re seeing the entire Royal Ballet tramp past – as Max Richter's score for string quintet and distant shortwave radio crackle rises to its melancholy climax. It’s a potent image of the individual vs. a mass of indifference. All the more credit to this fine revival for its entirely new cast of young dancers.

Oddly, the emotional arc feels more complete in Infra, the Wayne MacGregor piece that follows. I say oddly, because MacGregor is not known for emotional content, and in this work, made in 2008, half of the people we see on stage are walking holograms with circles for heads (pictured above). On a virtual walkway over the real dancer's heads march a mesmerising trail of luminous pin figures, courtesy of the artist Julian Opie. Some carry shopping or a briefcase, but they are faceless, oblivious, relentless. Below them, flesh-and-blood figures engage in tense couplings. Partners divide and form new pairs, each demanding an attention you can't give it as they grapple in a line at the front of the stage. The defining moment comes as one girl, left alone, kneels distressed centre-stage as a rush-hour load of real-life people surge past her. On and on they come – it seems as if we’re seeing the entire Royal Ballet tramp past – as Max Richter's score for string quintet and distant shortwave radio crackle rises to its melancholy climax. It’s a potent image of the individual vs. a mass of indifference. All the more credit to this fine revival for its entirely new cast of young dancers. Symphony in C, danced to the crystalline classicism of the teenage Bizet, brings the evening's focus on youth to a dazzling close. Is it fanciful to detect a sharpening of the company's classical sinews after the recent run of La Bayadere? There’s no stylistic workout more gruelling. Whatever, the corps look thoroughly at home in Balanchine’s gleaming symmetries, not to mention the unforgiving white tutus, and the soloists appear to be having a ball. Could a smile be any wider than Vadim Muntagirov’s, or landings cleaner? Could any ballerina be more regal in adage than Marianela Nunez? I’m willing to bet not. Those strange narcoleptic moments as she falls backward repeatedly into her partner’s arms – a reference to The Sleeping Beauty, I’m sure – had the whole house holding its breath, swooning with her.

Symphony in C, danced to the crystalline classicism of the teenage Bizet, brings the evening's focus on youth to a dazzling close. Is it fanciful to detect a sharpening of the company's classical sinews after the recent run of La Bayadere? There’s no stylistic workout more gruelling. Whatever, the corps look thoroughly at home in Balanchine’s gleaming symmetries, not to mention the unforgiving white tutus, and the soloists appear to be having a ball. Could a smile be any wider than Vadim Muntagirov’s, or landings cleaner? Could any ballerina be more regal in adage than Marianela Nunez? I’m willing to bet not. Those strange narcoleptic moments as she falls backward repeatedly into her partner’s arms – a reference to The Sleeping Beauty, I’m sure – had the whole house holding its breath, swooning with her.

Given the overall compositional fizz (allegro, adagio, allegro, allegro), and Balanchine’s fiendish cleverness in bringing all the teeming elements together in the final moments, few ballets send an audience home so happy.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment