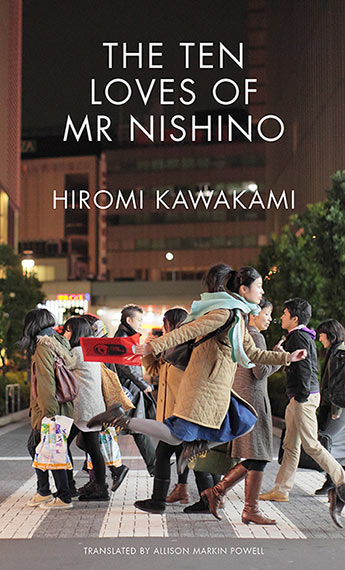

Hiromi Kawakami: The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino review - Don Juan as a salaryman | reviews, news & interviews

Hiromi Kawakami: The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino review - Don Juan as a salaryman

Hiromi Kawakami: The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino review - Don Juan as a salaryman

A besuited seducer seen through his lovers' eyes

My first, beguiling taste of Hiromi Kawakami’s fiction came when, in 2014, I and my fellow-judges shortlisted Strange Weather in Tokyo for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. That delicate, unsettling tale of a romance between a younger woman and an older man had lost its original title (The Briefcase) for something more obviously offbeat. Allison Markin Powell’s finely-phrased translation appeared a dozen years after the Japanese original.

True, Kawakami arguably shares some traits with the tiny cluster of contemporary female novelists from Japan allowed to cross the bridge into English – even though few readers would confuse her with the more overt absurdism of Banana Yoshimoto, or the richly Gothic twists and shocks of Yōko Ogawa. I suspect, though, that the resemblance owes more to a shared tradition of poetry and prose alike than to joint membership of some Pacific school of kooks. Certainly, The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino makes use a distinctively Japanese scaffolding, as its ten interlinked stories build into this multi-faceted mosaic of a novel.

Yukihiko Nishino, whom we glimpse in different settings with a variety of partners at successive stages of his life, is a sort of salaryman Don Juan. “Kind and courteous”, attentive to women and (above all) interested in their lives, he drifts from one affair to another, often running his liaisons in parallel. Although he pursues relationships, not just "conquests", his “deep-rooted tendency for cheating” inevitably results in one break-up after another. This “alluring company man” still feels that “I have never, to this day, loved a woman, in the true sense of the word”.

Crucially, Kawakami puts not our opaque charmer at the centre of her story, but ten women who fall for him. From the schoolgirl with a crush who observes Nishino from afar through student girlfriends to the middle-aged housewife who meets him at an “Energy-Saving Cooking Club” (he has joined, supposedly, to help sell his firm’s ecological cookware), we see the great seducer solely through his lovers’ eyes. They discern not some irresistible titan of passion, either heroic or demonic, but an ordinary guy, attractive and agreeable enough, but curiously hollow and (once gone) forgettable. One of these first-person narrators finds that he reminds her of her unreadable cat Maow, with “something feral, and yet delicate, in his expression”.

As a study in Don Juanism, Kawakami’s polygonal portrait looks a lot more convincing than most of the overblown literature on this theme in Western fiction, philosophy and psychology. For sure, she does drop hints of early troubles. We see the young-teenage Yukihiko suckling his elder sister’s lactating breast after she has lost a baby; later, we learn that she has committed suicide. Yet any trauma that lingers takes the form not of cruelty, violence of even blatant narcissism but, at most, a kind of congenital invisibility. It’s the obverse of the “slippery, elusive perfection” that gives him such lovely manners when hunting fresh prey: “Calling on the phone at the desired time. Calling at the right frequency. Using the desired words of praise. Offering the desired kindness.”

Nishino fails to save or ruin, even to change, these women’s lives, let alone his own. Rather, his – usually brief – passage through their apartments and routines allows Kawakami to sketch the ages of womanhood in the subtlest of inks. The seducer answers different needs at different times: for attention, romance, adventure, thrills, companionship – or just good-enough sex. For a period, he assuages the loneliness that stalks these outwardly content and comfortable lives. He knows how to act as the blank paper on which his lovers pen their wants. “Pure curiosity” rather than overwhelming passion leads some to take him to their bed.

Kawakami keeps the tone feather-light, iridescent, shimmering; the imagery of butterflies, dragonflies and fireflies fills these pages. Alison Markin Powell again responds with English brush-strokes of an equal swiftness and finesse. Although one woman alludes to John Fowles’s The Collector, Nishino’s story lacks both the chilling creepiness, and the tragic dimension, of that novel of erotic obsession.

Kawakami keeps the tone feather-light, iridescent, shimmering; the imagery of butterflies, dragonflies and fireflies fills these pages. Alison Markin Powell again responds with English brush-strokes of an equal swiftness and finesse. Although one woman alludes to John Fowles’s The Collector, Nishino’s story lacks both the chilling creepiness, and the tragic dimension, of that novel of erotic obsession.

Time passes; desire congeals into memory. Nishino’s ten loves glancingly report on his humdrum movement across the decades through our “relentless” universe of chance and fate. Recollections of Nishino – fond, annoyed, perplexed – knit themselves into the ever-changing fabric of busy, ordinary lives. One student girlfriend, who later rekindles their affair, decides that she loved Yukihiko in the same way as she loved her cat, or “the smell of sunshine on clean laundry”. As a corrective for the monstrous or majestic Don Juans of the West, we could do a lot worse than Kawakami’s modest, melancholy sensuality. The very word “love”, meanwhile, sounds to another woman like dusty curios bought at an antique shop: “Mementos from long ago piled in a jumble. Sort of nostalgic, and sad.”

- The Ten Loves of Mr Nishino by Hiromi Kawakami, translated by Allison Markin Powell (Granta, £12.99)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment