Lee Krasner: Living Colour, Barbican review - jaw-droppingly good | reviews, news & interviews

Lee Krasner: Living Colour, Barbican review - jaw-droppingly good

Lee Krasner: Living Colour, Barbican review - jaw-droppingly good

Eclipsed by her famous husband, a painter finally gets her due

If you know of any chauvinists who dare to maintain that women can’t paint, take them to this astounding retrospective. Lee Krasner faced patronising dismissal at practically every turn in her career yet she persisted and went on to produce some of the most magnificent paintings of the late 20th century.

Despite her brilliance, she is still known to most people as the wife of Jackson Pollock, whom she married in 1945, so it comes as no surprise to discover how hard it was for her to pursue her own path amid the male egos that dominated the New York art scene at the time. Among the abstract expressionists of her generation, the prevailing stereotype was of the anguished genius heroically struggling to pour out his soul onto canvas, and women simply didn’t fit the bill.

She knew she wanted to be an artist from the age of 14 and attended Washington High, the only school in New York offering art classes for girls. Her determination got her into the National Academy of Design in 1928, but won her no favours. “This student is always a bother… insists upon having her own way,” reads her report. She, in turn, condemned the school for its “sterile atmosphere…of congealed mediocrity.”

In life drawings classes she produced amazingly vigorous renditions of muscle and bone inspired by Michelangelo. Then she studied with Hans Hoffmann, who’d worked alongside Picasso and introduced his students to analytical cubism. Not only did he correct their drawings, but also tore them up and reassembled them. Krasner overlaid the model’s fleshy curves with a scaffolding of dynamic lines that implies both movement and structure.

In life drawings classes she produced amazingly vigorous renditions of muscle and bone inspired by Michelangelo. Then she studied with Hans Hoffmann, who’d worked alongside Picasso and introduced his students to analytical cubism. Not only did he correct their drawings, but also tore them up and reassembled them. Krasner overlaid the model’s fleshy curves with a scaffolding of dynamic lines that implies both movement and structure.

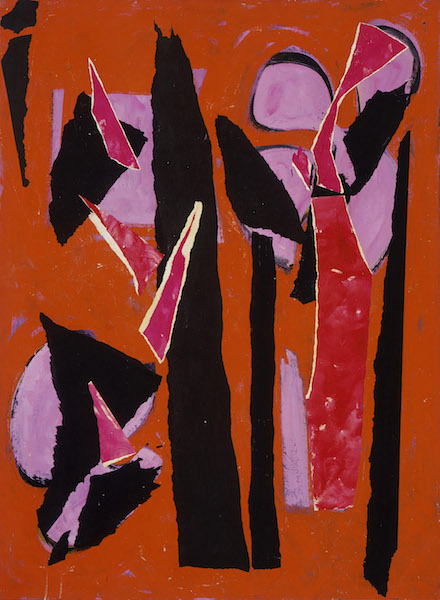

Hoffmann’s teaching had a lasting impact; it encouraged her ruthlessly to delete, reshape or even cut up and re-use things whenever she felt stuck. In 1951 she had an exhibition where nothing sold and this triggered an impasse. To get started again she covered her studio walls with drawings, only to tear them up in disgust. But the destruction prompted a series of collages made from the unsold canvases, cut into shards and reassembled into large, dynamic compositions (pictured above right: Desert Moon 1955).

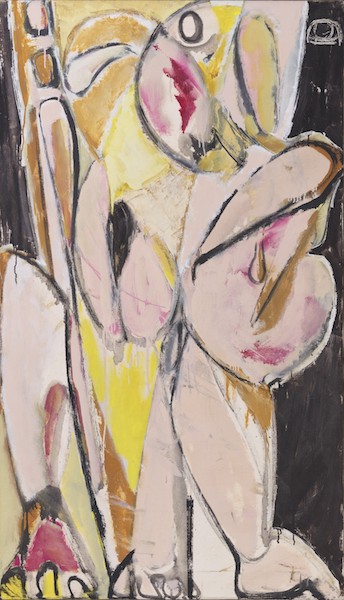

At another crucial moment – the summer of 1956 when Pollock was drinking heavily and having an affair – the fragmented, fleshy forms of her cubist drawings unexpectedly reappear in a series of paintings. Prophecy 1956 (pictured left) is imbued with a sense of panic and impotence; a distressed face overhangs contorted limbs awkwardly crammed into a narrow space. Krasner left the painting on her easel when she escaped to Paris, only to receive the news of Pollock’s fatal car crash.

At another crucial moment – the summer of 1956 when Pollock was drinking heavily and having an affair – the fragmented, fleshy forms of her cubist drawings unexpectedly reappear in a series of paintings. Prophecy 1956 (pictured left) is imbued with a sense of panic and impotence; a distressed face overhangs contorted limbs awkwardly crammed into a narrow space. Krasner left the painting on her easel when she escaped to Paris, only to receive the news of Pollock’s fatal car crash.

How to survive the tragedy? Her determination and resolve won through. She moved from her cramped upstairs studio into the barn where Pollock had produced his famous drip paintings and it proved to be another release. Suffering terrible insomnia, she worked at night, turning her anxiety into images charged with nervous energy. Polar Stampede, 1960 (pictured below) is a giant flurry of sepia arcs that elbow their way into view amid creamy splatters that hold the restless hordes in check. The canvas fills your field of vision and engulfs you in its explosive, edgy, desperate and euphoric energy. The effect is like being trapped amid a flock of birds flapping their wings in panic against a pane of glass.

Titles like Assault on the Solar Plexus, a defiant dance of weeping forms, indicate her emotional pain. Working kept her going, though. “Painting is like asking ‘Do I want to live?’,” she said. “My answer is ‘yes’, and I paint.” She was 47 and her most productive years were still to come.

As she recovered from her grief, the melancholy tones of the Night Journeys, as the nocturnal paintings are called, bloom into vibrant colour. Another Storm, 1963 feels calmer and more stable; sepia is replaced by alizarin crimson that lends this vast web of dynamic gestures the warmth and density of flesh so it pulsates with red-blooded vitality. The brushmarks are like ancient runes writ large by a giant hand. During the 1960s, her gestures get looser, freer, more exuberant and more calligraphic. The bulbous curves of buttocks, cheeks and thighs are still visible, but now they are dancing.

Then, in the early 1970s, comes another rebirth – to the hard-edge abstraction associated with the next generation – except that Krasner had already explored similar territory in her collage paintings of the 1950s and her colours are far more subtle and unexpected than anything attempted by Ellsworth Kelly or Kenneth Noland. Art critic Robert Hughes wrote that the crimsons, emerald greens and greys of Palingenesis, 1971 (main picture) “rap hotly on the eyeball at 50 paces”.

The Barbican’s retrospective is the first exhibition here of Lee Krasner’s work since Brian Robertson showed her at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1965. Palingenesis is Greek for rebirth and this inspiring show reveals Krasner’s amazing ability to reinvent herself and produce major works at every step of the way. Her paintings are a beautiful, dynamic, exhilarating hymn to the indomitable power of the human spirit. May she never again be eclipsed by Jackson Pollock.

The Barbican’s retrospective is the first exhibition here of Lee Krasner’s work since Brian Robertson showed her at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1965. Palingenesis is Greek for rebirth and this inspiring show reveals Krasner’s amazing ability to reinvent herself and produce major works at every step of the way. Her paintings are a beautiful, dynamic, exhilarating hymn to the indomitable power of the human spirit. May she never again be eclipsed by Jackson Pollock.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment