“People collect diamonds because they sparkle; or they sit on a bench in Cornwall and look out to sea”. At the Hayward Gallery for the opening of her retrospective, Bridget Riley speaks of such uncomplicated pleasures with evident delight. To experience Riley’s works is to be exposed afresh to the thrill of seeing, the sensations induced by her optically challenging fields of lines, curves, spots and waves an unapologetic, bodily reminder that perception is a mechanism over which we have no control, a process that is mysterious and powerful, and fundamental to being alive.

They may look like optical tricks, but Riley’s paintings owe more to the observation of light catching the motion of water, or dappled sun playing through leaves, than to science. Ranks of painted stripes shimmer as the colours merge and separate; geometric patterns in black and white dance and quiver, sometimes so violently that the picture surface seems to buckle, or even to dissolve.

Displayed on the walls of the Hayward’s upper gallery, along with examples of work from Riley’s student days, are the meticulously detailed preparatory works relating to some of these pieces. Designs are laid out on graph paper, the colours painted on, or applied with glue from wads of precut, coloured paper in a fashion reminiscent of Matisse’s cut-outs. Observations and changes are marked in pencil, the final composition arrived at through a gradual process of looking and doing, looking and doing again.

Displayed on the walls of the Hayward’s upper gallery, along with examples of work from Riley’s student days, are the meticulously detailed preparatory works relating to some of these pieces. Designs are laid out on graph paper, the colours painted on, or applied with glue from wads of precut, coloured paper in a fashion reminiscent of Matisse’s cut-outs. Observations and changes are marked in pencil, the final composition arrived at through a gradual process of looking and doing, looking and doing again.

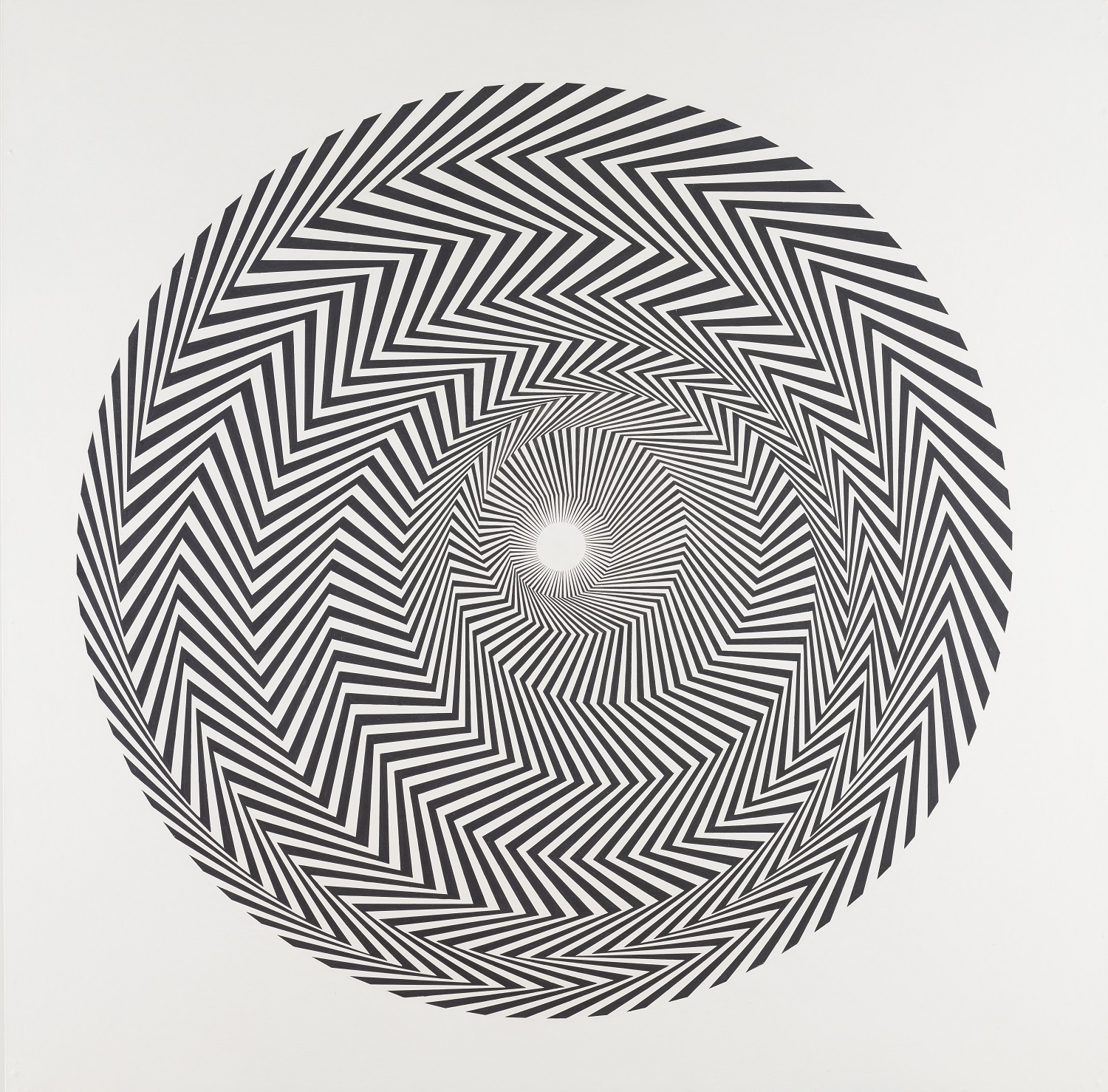

Riley’s approach embraces method and disorder in equal measure, and nowhere is this more evident than in the black-and-white paintings that brought her to prominence in the early 1960s. Here she isolates form – as a geometric shape, or as a line – and tests it, amplifying it through repetition and distortion to, as she describes it, “put it through its paces.”

Repetition for Riley is not a means to certainty, still less a shorthand for solidity. Instead, it induces collapse or release through the steady building of tension. In Blaze 1, 1962 (Pictured above right), zigzagged lines radiate out from a central point. Slight changes in angle and frequency destabilise an otherwise regular pattern, producing a dizzying vortex that dissolves as it gathers pace.

In Movement in Squares, 1961 (Main picture), the apparently unshakeable stability of a chequerboard is disrupted, the squares gradually narrowing until at one point – the breaking point – they seem to disappear, sucked into a vacuum beyond. Timing is essential to the impact of this moment, and the anxiety it induces is only heightened by its transience – almost as soon as it is sucked into its inexplicable chasm, the chequerboard starts to right itself, settling once more to a rhythm.

It’s the result of a profoundly intuitive, artistic judgement, that allows us to reconcile this monochrome, geometric world with lived experience, mediated through the senses. In fact, Movement in Squares can start to look like a very painterly painting, engaged with traditional artistic concerns of space, light and movement. Here, as in many of the black-and-white paintings, the sensation of movement both generates and is achieved by the illusion of pictorial depth and the action of light. The chequerboard seems to disappear around a curve, and though this is achieved solely through the narrowing dimensions of the squares, we bring to it our own knowledge of the way in which light behaves.

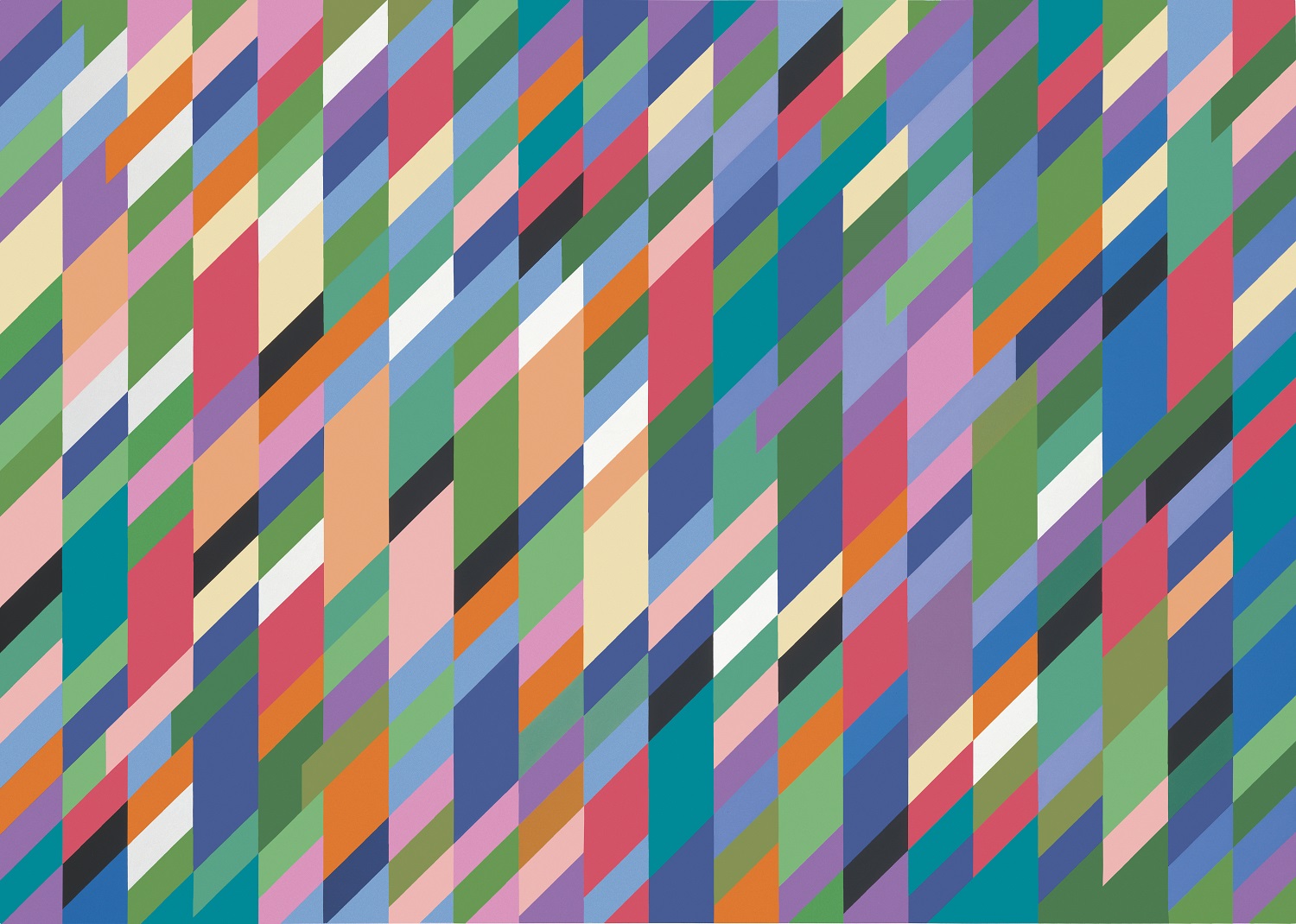

Riley began to introduce colour to her work in the late 1960s, a development that produced subtler paintings, less obviously reliant on visual shocks than those made in black and white (Pictured above: High Sky, 1991). In the stripe paintings of the late Sixties, we can see not only her interest in colour as a carrier of light but her active and highly intelligent engagement with the art of the past.

Riley began to introduce colour to her work in the late 1960s, a development that produced subtler paintings, less obviously reliant on visual shocks than those made in black and white (Pictured above: High Sky, 1991). In the stripe paintings of the late Sixties, we can see not only her interest in colour as a carrier of light but her active and highly intelligent engagement with the art of the past.

The work of Georges Seurat (1859-1891), whose A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte – 1884 attempted to introduce to painting the systematic application of optical theory, has been a lifelong source of inspiration for Bridget Riley, and the stripe paintings in particular can be seen as a development of his ideas. Free from the burden of representation, Riley’s paintings are no less engaged with the experience of the visible world: on the contrary, by isolating colour and removing from it the task of describing form, her analysis gains focus and intensity.

For Riley, the stripe is the equivalent of Seurat’s dot or dash, the long edges providing a site for the action of light. In Rise 1, 1968, evenly spaced lines of red, blue, green and white begin to do what you feel Seurat knew they might, the colours merging and even separating, so that yellow starts to shine through, like the memory of sunlight creeping through a blind.

- Bridget Riley at the Hayward Gallery until 26 January 2020

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment