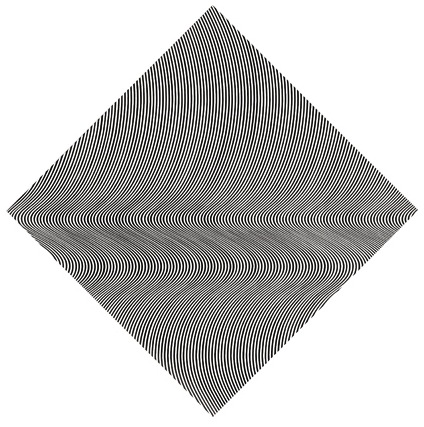

If they remember the 1960s at all, the ageing population of Bexhill-on-Sea will remember Bridget Riley for her black and white experiments in perception. The iconic results of this line of enquiry can still result in a “happening” for the eyeballs. And that’s exactly what you get from the earliest paintings in this show: uniform stripes of black and white that won’t for a moment stay still.

Crest, 1964 (pictured below right), is particularly dazzling, with a pair of whiplash curves that speed up before your eyes and ripple back and forth at a bewildering pace. Crest leaps out of its chronological context and unhinges your reception of the rest of this show before you’ve even really begun. It reminds you that Riley hit upon an art historical motif as familiar as Dalí’s melting watches or Mondrian’s squared primary colours.

All of which is a bit of an issue for De La Warr Pavilion, which offers a core sample of Riley’s career from the point of view of the curve. Her unruly works from the Sixties compel the gaze and perform a trick which still stuns the senses, and leave you ill-prepared for the later subtleties of this artist’s enduring career. The 21st-century Riley, for example, remains a magician, but she lately offers calm and sensual (rather than hallucinatory) pleasures.

In the 1970s she tones down the violence and warms up her paintings with coloured waves, which twist and shimmy up and down your field of view. The aim now is to evoke rhythms rather than to terrorise. Colours prove gentler than black and white could ever be; and so Andante 1 (pictured below left), for example, undulates two or three inches off the linen ground with muted shades of mauve, peach, lime and turquoise: a restrained palette for a restrained work.

In the 1970s she tones down the violence and warms up her paintings with coloured waves, which twist and shimmy up and down your field of view. The aim now is to evoke rhythms rather than to terrorise. Colours prove gentler than black and white could ever be; and so Andante 1 (pictured below left), for example, undulates two or three inches off the linen ground with muted shades of mauve, peach, lime and turquoise: a restrained palette for a restrained work.

But that is the end of the overt trickery. Between 1980 and 1997 Riley abandoned the curve or, as she puts it in the catalogue, the curve was “banished”. There is a 17-year hiatus in her output of the form which proves the second great challenge for this thematic show. But the De La Warr Pavilion has managed to build a bridge using a display of studies spanning the full chronology of such works. And here the graph paper, the coded initials, the tracing paper, and the collage all leave you with the impression of an avid problem-solver and a masterful technician.

When Riley re-emerges towards the millennium with planes of colour, it is a triumphant return. The palette is bolder, the rhythms bolder and the relation to art history much clearer. Riley has been studying Matisse, Cézanne and Seurat, to name but a few painters. And here the curve comes full circle, since early experience in life drawing has given her work a sense of figuration and dance; later paintings may be abstract but, as the artist will tell you, evoke dynamic human poses, with art historical labels.

Indeed when Riley begins to speak of contrapposto and la figura serpentina, as she has done for this and other shows, she calls to mind another artist-engineer of the curve. And that unlikely figure is US sculptor Richard Serra, whose own touchstones are torque and ellipse. While different on first and even second glance, both artists now work on a monumental scale and with a set of spatial and material challenges which set them off in lonely pursuit of perfection.

Indeed when Riley begins to speak of contrapposto and la figura serpentina, as she has done for this and other shows, she calls to mind another artist-engineer of the curve. And that unlikely figure is US sculptor Richard Serra, whose own touchstones are torque and ellipse. While different on first and even second glance, both artists now work on a monumental scale and with a set of spatial and material challenges which set them off in lonely pursuit of perfection.

And so the later work here is characterised by contrasting pairs of colours and steady pulses of horizontal movement broken by vertical staves. There is still illusion at work; contrast brings different colours to the foreground at different moments, while pushing others back. And Riley is still a painter who, despite eschewing perspective, works superbly in three dimensions. In that respect at least, her carefully made pictures are not so different from sculpture.

It won’t drive you cross-eyed, but her most exciting composition here is a mural entitled Rajasthan (main picture). This 2012 work is a flickering frieze of orange, red, green and grey into which the white wall of the gallery is making disruptive incursions. By pushing beyond the confines of the picture plane, Riley continues to push the boundaries of painting. The 84-year-old’s stamina is as spectacular as her work.

With that two-decade period of abstinence, Bridget Riley: The Curve Paintings was always going to be tricky and indeed this is an uneven show. If they were not painted by the same person her vision-jamming black and white pieces and her serene later works would have no place in the same space. Not even the elegant architectural sweep of the De La Warr Pavilion manages to bring all the works here into line. But look from the gallery to the sea and you’ll find a blue horizon wide enough to encompass any number of painterly innovations. It is perhaps against this curve of expectation that Riley persists in testing herself.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment