Caroline Moorehead: A House in the Mountains review – the women's war against Fascism | reviews, news & interviews

Caroline Moorehead: A House in the Mountains review – the women's war against Fascism

Caroline Moorehead: A House in the Mountains review – the women's war against Fascism

Uplifting, and horrifying, stories of the Italian Resistance and its heroines

In September 1944, a heavily pregnant Resistance activist in the north of German-occupied Italy was arrested on a visit to Milan. Lisetta Giua, a law student and fiancée of the Jewish anti-Fascist chief Vittorio Foa, worked as one of hundreds of women staffette: vital underground operatives whose roles might stretch from courier and spy to liaison officer and saboteur.

Then, in “an extraordinary stroke of luck”, the German Wehrmacht decided that Koch’s shameless, SS-protected monsters were attracting too much attention, and closed them down. Koch himself knew that the days of Mussolini’s German-dominated “Salò Republic” in northern Italy were numbered. The invading Allies moved up from the South while the region's partisan guerrillas grew bolder, and more effective, every day. Koch tried to broker a deal with the partisans: help him escape to Switzerland and the tortured militants of the Villa Triste could go free. The Resistance leader who had to tell Koch that “With hyenas, we do not deal” was – Vittorio Foa himself. Distraught, in despair, Foa visited an old friend. They listened to Beethoven’s “Eroica” symphony in silence. But the survivors of the Villa Triste were transferred to an ordinary jail. Lisetta learned there from a sympathetic gynaecologist how to feign complications of her pregnancy. When she moved to a maternity home, under less secure guard, another Resistance heroine named Gigliola Spinelli, “a bold planner of improbable stunts”, turned up disguised as a nurse. Along with four armed partisans, she spirited Lisetta back to Turin.

Mother and baby both survived, and thrived. After a long career in left-wing journalism and politics, Lisetta died in 2005 (she appears, by the way, in Family Lexicon, the classic autobiographical novel by her Turin friend Natalia Ginzburg). Her story might make a book of its own. So might the experiences of a score of other extraordinary women – or rather, ordinary women who rose to their extraordinary times – whom we meet in A House in the Mountains. As biographer and historian, Caroline Moorehead has repeatedly recounted the lives of women and men who found the will, the skill and above all the bravery to oppose conformity, persecution and violence in defence of justice and freedom. Her recent books – A Train in Winter, Village of Secrets, A Bold and Dangerous Family – have not only told utterly gripping stories of the steadfast few who refused to obey Nazi and Fascist tyranny. She asks how, and where, some people find the courage to resist.

A House in the Mountains adds to this remarkable sequence in its crowded fresco of stories about prominent women of the Italian Resistance, mostly in and around Turin. The bulk of Moorehead’s narrative covers the brief, messy and intense 20 months between the armistice of September 1943, when Italy accepted Allied peace terms only for much of the country to be brutally occupied by their German former co-belligerents, and the end of the European war in May 1945. In Turin itself, and in the Alpine valleys and mountains to the west, networks of idealistic anti-Fascist friends quickly became partisan fighters. Moorehead stresses the Piedmont area’s historic “spirit of independence and rebellion”. Many of her protagonists came either from Protestant families – the persecuted Waldensians had their heartland in these isolated valleys – or from Jewish backgrounds. Primo Levi, a much-loved member of these circles and a Resistance worker before his deportation to Auschwitz, makes regular appearances. The friends' politics ranged from liberalism to Communism, although mutual respect and affection overrode ideology. Ada Gobetti acts as Moorehead’s linchpin for her many-faceted tale – a key Resistance leader, journalist and translator, and widow of the murdered anti-Fascist thinker Piero Gobetti. Her chalet in the mountains outside Turin became a hub of dissident thinking and strategy. Ada (pictured above after the liberation of Turin) wrote that “I don’t have political ideas, only moral certainties.”

A House in the Mountains adds to this remarkable sequence in its crowded fresco of stories about prominent women of the Italian Resistance, mostly in and around Turin. The bulk of Moorehead’s narrative covers the brief, messy and intense 20 months between the armistice of September 1943, when Italy accepted Allied peace terms only for much of the country to be brutally occupied by their German former co-belligerents, and the end of the European war in May 1945. In Turin itself, and in the Alpine valleys and mountains to the west, networks of idealistic anti-Fascist friends quickly became partisan fighters. Moorehead stresses the Piedmont area’s historic “spirit of independence and rebellion”. Many of her protagonists came either from Protestant families – the persecuted Waldensians had their heartland in these isolated valleys – or from Jewish backgrounds. Primo Levi, a much-loved member of these circles and a Resistance worker before his deportation to Auschwitz, makes regular appearances. The friends' politics ranged from liberalism to Communism, although mutual respect and affection overrode ideology. Ada Gobetti acts as Moorehead’s linchpin for her many-faceted tale – a key Resistance leader, journalist and translator, and widow of the murdered anti-Fascist thinker Piero Gobetti. Her chalet in the mountains outside Turin became a hub of dissident thinking and strategy. Ada (pictured above after the liberation of Turin) wrote that “I don’t have political ideas, only moral certainties.”

The adventures, and ordeals, of three other women apart from Ada anchor the narrative: medical student Silvia Pons; junior lawyer Bianca Guidetta Serra; literature graduate Frida Malan. All in some way inherited, or acquired, Protestant, Jewish or other non-conformist family legacies. Their contacts and affiliations stretched from the philosopher Benedetto Croce, and the intellectual aristocracy of anti-Fascist Italy, to the Communist trade unionists of the FIAT car plants and other factories in Turin and the valleys. Working underground, forever at risk of capture, torture and execution (a fate that befell countless other fighters who stride across Moorehead’s pages), these women helped the Resistance of 1943-45 find shelter and support across Piedmont.

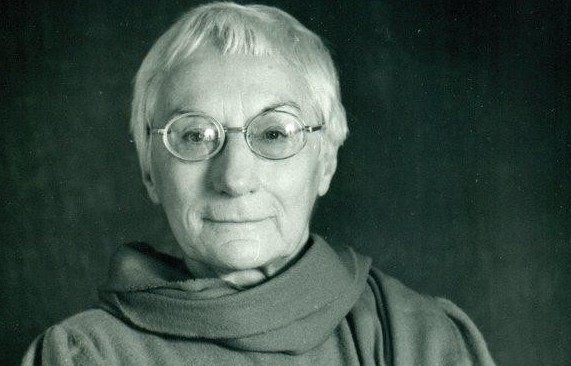

In turn, their Resistance activism gave them a home and a role undreamed of before. Mussolini’s “steady disenfranchisement of Italian women” had wiped out the frail advances of the early 20th century. Church and state enforced women's lowly status as obedient housewives and mothers. But as young women flocked to the partisans as staffette – which could mean almost anything except front-line combat, and even that became women’s work as liberation neared – for the first time they “could imagine having opinions and voicing them”. More than that: they took on leadership positions as trainers, propagandists, commanders and commissars. This was a war “nested in kitchens”, as one warrior wrote. The anti-Fascist uprising spawned an internal revolution of gender emancipation. Women’s Resistance cells, known as the GDD, mushroomed as if in response to a “ferocious hunger for knowledge and responsibility”. Bianca (pictured below in later life), in common with many of her comrades, equated “the fight for the liberation of Italy, and the fight for the liberation of women”.

Crammed with dramatic and often horrifying incident, A House in the Mountains tells this story – of the awakening of a “mass social conscience” among partisan-allied women – alongside the overall narrative of bitter combat against the Germans and local Fascists. Meanwhile, the slow Allied advance through Italy brought in its wake confused diplomatic and military manoeuvres that Moorehead has to unravel. It makes for a fiendishly complex landscape; a “labyrinth of conflicting parties, bands, groups, allegiances and rivalries”. Yet, for all these taxing convolutions, the breath-stopping bravery of her four protagonists and their comrades, women and men alike, keeps the reader utterly immersed. Gentle idealists like Emanuele Artom – another Turin Jewish partisan – had not only to learn to kill in combat, but to order the execution of traitors. Emanuele, like many of the spirits snuffed out in the course of this story, died after severe torture. Not only the field combatants leave an unforgettable impression. Quiet heroism comes from figures such as the invincible nun Suor Giuseppina, in change of the women’s section in Turin prison. Her “mixture of charm and steeliness” disarmed and deflected Nazi brutality time and time again.

Crammed with dramatic and often horrifying incident, A House in the Mountains tells this story – of the awakening of a “mass social conscience” among partisan-allied women – alongside the overall narrative of bitter combat against the Germans and local Fascists. Meanwhile, the slow Allied advance through Italy brought in its wake confused diplomatic and military manoeuvres that Moorehead has to unravel. It makes for a fiendishly complex landscape; a “labyrinth of conflicting parties, bands, groups, allegiances and rivalries”. Yet, for all these taxing convolutions, the breath-stopping bravery of her four protagonists and their comrades, women and men alike, keeps the reader utterly immersed. Gentle idealists like Emanuele Artom – another Turin Jewish partisan – had not only to learn to kill in combat, but to order the execution of traitors. Emanuele, like many of the spirits snuffed out in the course of this story, died after severe torture. Not only the field combatants leave an unforgettable impression. Quiet heroism comes from figures such as the invincible nun Suor Giuseppina, in change of the women’s section in Turin prison. Her “mixture of charm and steeliness” disarmed and deflected Nazi brutality time and time again.

After a punishing winter, “medieval in its horrors”, the partisans gained the upper hand and prepared for the insurrection of 26 April 1945. Although supported by (sometimes half-hearted) Allied air-drops and by (often patronising) British and US liaison officers, the Resistance of Turin and Piedmont achieved victory on their own – and with women at the heart of the campaign. A female-led general strike in Turin on 18 April left the Germans looking “like beaten dogs” (although they then shot 36 women strikers). After Resistance units came down from the mountains to seize the city, Ada herself became the vice-mayor – a breakthrough in itself for Italian public life.

High-minded partisans agonised over the spasm of bloody reprisals that followed the liberation, with around 2500 extra-judicial killings of Nazis and Fascists in Piedmont. Should events such as the summary execution of Mussolini himself and his mistress be seen as “Mexican-style butchery”, as partisan-turned-prime minister Ferruccio Parri thought, or “a necessary gesture of reckoning”? After the brief vendetta, however, not only did many elements of old-fashioned normality resume as the Allies sought to strangle Communist influence. From the Church to FIAT, the old powers carried on as before, their collusion with Fascists and Germans conveniently forgotten. The Communist Party itself, “more Catholic than the Catholics” in its views on family life, endorsed much of the status quo. Women were expected to get back into the home and to stifle their pleas for liberty. Post-war Italy felt, to one Resistance figure, “feeble, slack and full of fear”. One woman wrote of being “sent home like chickens to the coop to lay our eggs in solitude and silence”. Another remembered that, after the Resistance, “We thought we would find a new world. We didn’t.”

High-minded partisans agonised over the spasm of bloody reprisals that followed the liberation, with around 2500 extra-judicial killings of Nazis and Fascists in Piedmont. Should events such as the summary execution of Mussolini himself and his mistress be seen as “Mexican-style butchery”, as partisan-turned-prime minister Ferruccio Parri thought, or “a necessary gesture of reckoning”? After the brief vendetta, however, not only did many elements of old-fashioned normality resume as the Allies sought to strangle Communist influence. From the Church to FIAT, the old powers carried on as before, their collusion with Fascists and Germans conveniently forgotten. The Communist Party itself, “more Catholic than the Catholics” in its views on family life, endorsed much of the status quo. Women were expected to get back into the home and to stifle their pleas for liberty. Post-war Italy felt, to one Resistance figure, “feeble, slack and full of fear”. One woman wrote of being “sent home like chickens to the coop to lay our eggs in solitude and silence”. Another remembered that, after the Resistance, “We thought we would find a new world. We didn’t.”

Moorehead’s quartet of heroines all lived; indeed, the radical lawyer Bianca Guidetti Serra only died – aged 95 – in 2014. They left the diaries, the letters, the documents and the family memories that have allowed her to tell their eye-opening and spirit-lifting stories so powerfully. If many of their hopes for postwar liberation were dashed, they and others would later resume the fight. In any case, the memory of the Resistance as “a time of heady equality” never deserted them. Even if, as Ada wrote, “we knew that our lives would never be that exciting again”.

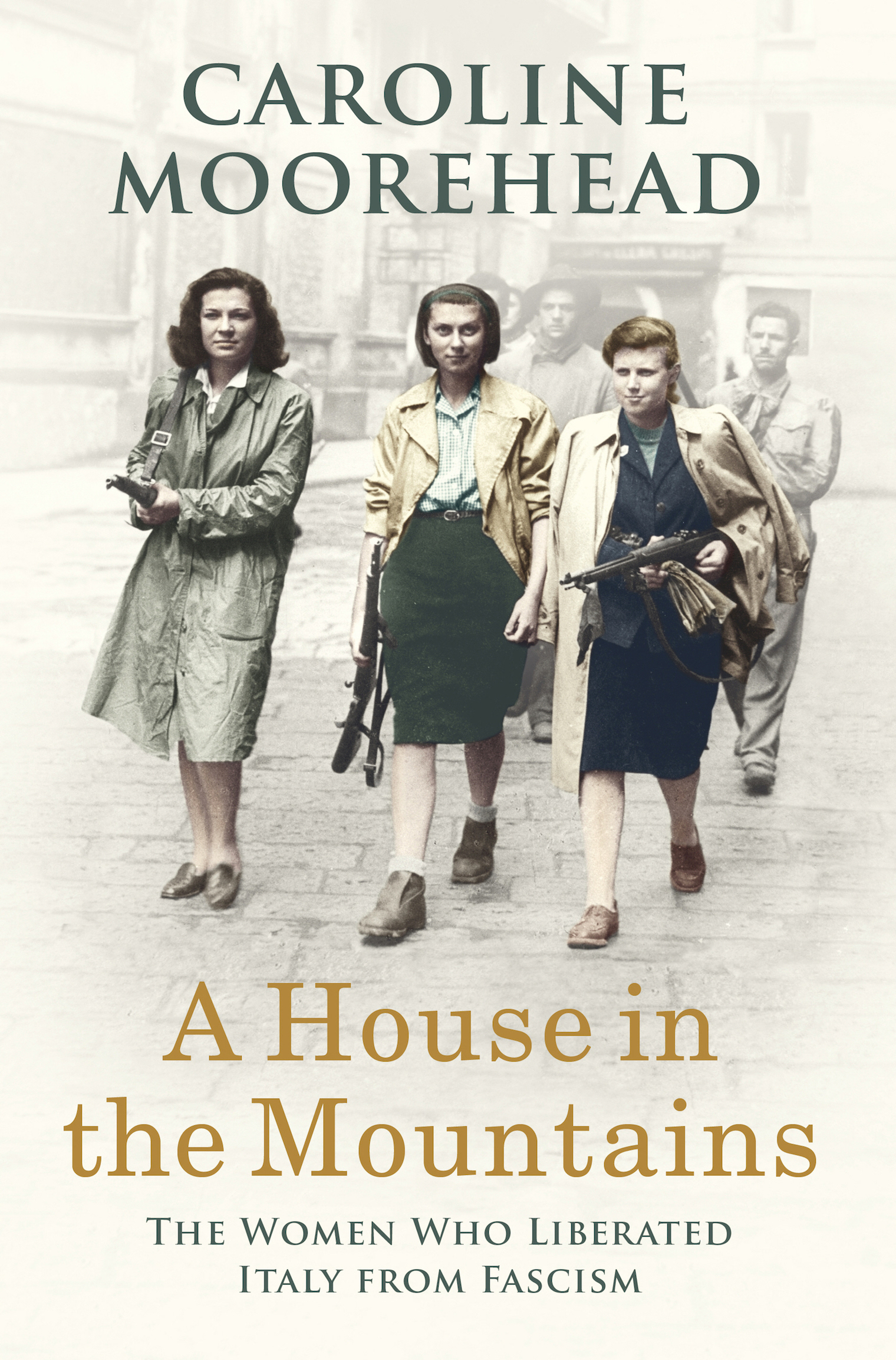

A House in the Mountains: the Women who Liberated Italy from Fascism by Caroline Moorehead (Chatto & Windus, £20)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Comments

I wrote a biography of Ada