Best of 2019: Books | reviews, news & interviews

Best of 2019: Books

Best of 2019: Books

Cover to cover, this year's top titles

In a year that saw some notable highs (Ilya Kaminsky's Deaf Republic) and some stonking lows (Jacob Rees-Mogg's much-derided The Victorians) our reviewers share their top picks – some of which we covered, others which we didn't.

How odd that, in an age of grotesquely inflated Netflix series, the very idea of a thousand-page novel should still sow wonderment – or panic. Happily, readers who dived into Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (Galley Beggar Press) enjoyed a banquet that may be wolfed or sipped at will, torn off in greedy chunks or gently nibbled day-by-day. The meandering single-sentence monologue of Ellmann’s Ohio housewife and baker – “a homemaker, and a piemaker” – spans the perfect tarte tatin recipe, the invisible dramas of maternity, and the fate of a ravaged planet; it links our everyday joys and fears to the “constant state of alarm” fostered by acts of violence and injustice, large and small. Ellmann’s intimate epic braids the local and the global not just with cascading verbal brilliance but a wit, charm and compassion that make our fretful baker one of modern fiction’s most compelling companions. “Nobody seems to notice, cooking or motherhood,” she frets. Ellmann richly honours both. Boyd Tonkin

How odd that, in an age of grotesquely inflated Netflix series, the very idea of a thousand-page novel should still sow wonderment – or panic. Happily, readers who dived into Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann (Galley Beggar Press) enjoyed a banquet that may be wolfed or sipped at will, torn off in greedy chunks or gently nibbled day-by-day. The meandering single-sentence monologue of Ellmann’s Ohio housewife and baker – “a homemaker, and a piemaker” – spans the perfect tarte tatin recipe, the invisible dramas of maternity, and the fate of a ravaged planet; it links our everyday joys and fears to the “constant state of alarm” fostered by acts of violence and injustice, large and small. Ellmann’s intimate epic braids the local and the global not just with cascading verbal brilliance but a wit, charm and compassion that make our fretful baker one of modern fiction’s most compelling companions. “Nobody seems to notice, cooking or motherhood,” she frets. Ellmann richly honours both. Boyd Tonkin

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez (Chatto & Windus) is the game changer of the year and should be mandatory reading for every adult of any gender. Criado Perez sets out to show how living in a world designed by men, for men, is harmful to women on all levels – from the psychological and economic to the legal and the medical. By disadvantaging half the world’s population, all of us are harmed. This calm, dispassionate, hilarious, entertaining, maddening, infuriating narrative is a highly readable manifesto for real change. Silk Roads, Peoples, Cultures, Landscapes edited by Susan Whitfield (Thames & Hudson) is a superbly illustrated volume written by 80 scholars who, in short essays, tell the millennia-long story of the historic trade routes that criss-cross half the world, from Asia to Europe. The huge variety of the travellers and the merchandise along these complex trajectories is handsomely laid out in this delightful, informative and continually surprising work. Marina Vaizey

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez (Chatto & Windus) is the game changer of the year and should be mandatory reading for every adult of any gender. Criado Perez sets out to show how living in a world designed by men, for men, is harmful to women on all levels – from the psychological and economic to the legal and the medical. By disadvantaging half the world’s population, all of us are harmed. This calm, dispassionate, hilarious, entertaining, maddening, infuriating narrative is a highly readable manifesto for real change. Silk Roads, Peoples, Cultures, Landscapes edited by Susan Whitfield (Thames & Hudson) is a superbly illustrated volume written by 80 scholars who, in short essays, tell the millennia-long story of the historic trade routes that criss-cross half the world, from Asia to Europe. The huge variety of the travellers and the merchandise along these complex trajectories is handsomely laid out in this delightful, informative and continually surprising work. Marina Vaizey

Show Them a Good Time (Bloomsbury), Nicole Flattery’s bitingly original collection of short stories, follows disaffected young women in “self-imposed exile, searching for meaning they might never find”. One protagonist returns to her hometown, “famous amongst people with car-sickness”, to work in a motorway service station under the suspicious gaze of “Management” which tries to thrust employees into the habits of organisation and “responsibility”. Another becomes fixated on the hump she is sure is growing beneath her shoulders after her father’s death. In "Track", the girlfriend of a famous comedian settles into the ritual of listening to a recording of his 12-year-old comedy routine, all the while attacking his persona anonymously online. Flattery is interested in futility, indirection and pretence and these stories build atmospheres of alienation and listlessness, themes she treats with an abrupt, deadpan humour. Nimbly weird, often ominous, and very, very funny, Show Them a Good Time offers precise insights into relationships, social performance and self-scrutiny, powerfully capturing the blankness of modern living. It marks a confident, compulsive debut. Jessica Payn

Show Them a Good Time (Bloomsbury), Nicole Flattery’s bitingly original collection of short stories, follows disaffected young women in “self-imposed exile, searching for meaning they might never find”. One protagonist returns to her hometown, “famous amongst people with car-sickness”, to work in a motorway service station under the suspicious gaze of “Management” which tries to thrust employees into the habits of organisation and “responsibility”. Another becomes fixated on the hump she is sure is growing beneath her shoulders after her father’s death. In "Track", the girlfriend of a famous comedian settles into the ritual of listening to a recording of his 12-year-old comedy routine, all the while attacking his persona anonymously online. Flattery is interested in futility, indirection and pretence and these stories build atmospheres of alienation and listlessness, themes she treats with an abrupt, deadpan humour. Nimbly weird, often ominous, and very, very funny, Show Them a Good Time offers precise insights into relationships, social performance and self-scrutiny, powerfully capturing the blankness of modern living. It marks a confident, compulsive debut. Jessica Payn

The Capital (MacLehose Press) is anything but your predictable EU satire. Austrian Robert Menasse is an imaginative novelist, not a polemicist (for that, read his fascinating non-fiction offshoot, Enraged Citizens, European Peace and Democratic Deficits, which praises the transparency of the Brussels set-up but laments the flaw of admitting nationalisms in the form of the Council). Like all good satires, it's deeply serious at heart. Mortality is a theme, and while the Berlaymont is central, there are also scenes in Vienna, Krakow and Auschwitz, as well as a polyphonic array of idealists and bureaucrats. It is tantalisingly open-ended. Translator Jamie Bulloch is crucial in making you feel that this is the work of a master of the Engish language – and long live MacLehose Press for continuing the essential work of bringing us the best of continental European literature in translation. George Szirtes' The Photographer at Sixteen was a smaller-scale gem - actually written in English - and I'm eager for Volume Three of the Estonian Wolf Hall, the long overdue translation of Jaan Kross's Between Three Plagues trilogy, due in 2020. David Nice

The Capital (MacLehose Press) is anything but your predictable EU satire. Austrian Robert Menasse is an imaginative novelist, not a polemicist (for that, read his fascinating non-fiction offshoot, Enraged Citizens, European Peace and Democratic Deficits, which praises the transparency of the Brussels set-up but laments the flaw of admitting nationalisms in the form of the Council). Like all good satires, it's deeply serious at heart. Mortality is a theme, and while the Berlaymont is central, there are also scenes in Vienna, Krakow and Auschwitz, as well as a polyphonic array of idealists and bureaucrats. It is tantalisingly open-ended. Translator Jamie Bulloch is crucial in making you feel that this is the work of a master of the Engish language – and long live MacLehose Press for continuing the essential work of bringing us the best of continental European literature in translation. George Szirtes' The Photographer at Sixteen was a smaller-scale gem - actually written in English - and I'm eager for Volume Three of the Estonian Wolf Hall, the long overdue translation of Jaan Kross's Between Three Plagues trilogy, due in 2020. David Nice

Maria Popova’s Figuring (Canongate) picked up on a contemporary interest in forgotten women, tracing a temporal line through their stories. With a root in astronomy and mathematics, Popova’s book was as descriptive as it was factual, lyrically following the lives of characters like Margaret Fuller, the pioneering feminist writer, who tragically drowned within sight of land, and Maria Mitchell, whose astronomical career began with the discovery of a comet, for which she was awarded a medal by the King of Denmark. Figuring focused not only on biographical detail but also the intricacies of the human heart and the struggle of being a woman in male-dominated areas. It was fascinating and compelling written, bringing the reader into the lives of its subjects, ending with a long description of Rachel Carson’s life that has only made me love her more. India Lewis

Maria Popova’s Figuring (Canongate) picked up on a contemporary interest in forgotten women, tracing a temporal line through their stories. With a root in astronomy and mathematics, Popova’s book was as descriptive as it was factual, lyrically following the lives of characters like Margaret Fuller, the pioneering feminist writer, who tragically drowned within sight of land, and Maria Mitchell, whose astronomical career began with the discovery of a comet, for which she was awarded a medal by the King of Denmark. Figuring focused not only on biographical detail but also the intricacies of the human heart and the struggle of being a woman in male-dominated areas. It was fascinating and compelling written, bringing the reader into the lives of its subjects, ending with a long description of Rachel Carson’s life that has only made me love her more. India Lewis

In an age when every famous-for-five-minutes so-called celebrity thinks theirs is a life fascinating enough to appear between hard covers, it’s refreshing that one of Britain’s truly talented musicians waits until he’s poised to retire before writing his memoirs. Publishers have for years been after Elton John, who presumably had better things to go than sit down and get his head round his journey down the yellow brick road from Pinner, but this year, working with Alexis Petridis, he produced Me (Macmillan) a dizzying, dazzling journey – potholes and all. Whether Me will age as well as David Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon remains to be seen but it is a great read, laugh-out-loud moments providing cheer in an existentially drear year. The voice is Elton’s, and many of the anecdotes are priceless: a coke-fuelled Elton mistaking a shambling Bob Dylan for the gardener and, learning of his mistake, attempts to get him out of “those terrible clothes” and into some of his own as George Harrison advises him to “go steady on the old marching powder”. He also reveals that Dylan was hopeless at Charades because he could never figure out how many syllables a word contained. There’s the falling out with Tina Turner – with whom he was considering a tour until she had the temerity to tell him his clothes and hair were all wrong (“too much Versace, and it makes you look fat”). And the final straw – telling him he didn’t know how to play “Proud Mary”. Me is full of thrills, spills and craziness. An essential book for the shelf. Liz Thomson

In an age when every famous-for-five-minutes so-called celebrity thinks theirs is a life fascinating enough to appear between hard covers, it’s refreshing that one of Britain’s truly talented musicians waits until he’s poised to retire before writing his memoirs. Publishers have for years been after Elton John, who presumably had better things to go than sit down and get his head round his journey down the yellow brick road from Pinner, but this year, working with Alexis Petridis, he produced Me (Macmillan) a dizzying, dazzling journey – potholes and all. Whether Me will age as well as David Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon remains to be seen but it is a great read, laugh-out-loud moments providing cheer in an existentially drear year. The voice is Elton’s, and many of the anecdotes are priceless: a coke-fuelled Elton mistaking a shambling Bob Dylan for the gardener and, learning of his mistake, attempts to get him out of “those terrible clothes” and into some of his own as George Harrison advises him to “go steady on the old marching powder”. He also reveals that Dylan was hopeless at Charades because he could never figure out how many syllables a word contained. There’s the falling out with Tina Turner – with whom he was considering a tour until she had the temerity to tell him his clothes and hair were all wrong (“too much Versace, and it makes you look fat”). And the final straw – telling him he didn’t know how to play “Proud Mary”. Me is full of thrills, spills and craziness. An essential book for the shelf. Liz Thomson

Zahra Hankir’s pioneering collection Our Women on the Ground (Harvill Secker) is required reading. With stories from Christine Amanpour, Chief International Anchor for CNN, to Ruqia Hussain, citizen journalist who reported from inside occupied Raqqa on Facebook, it disrupts traditional narratives surrounding conflict reporting and Arab women to perform an act of solidarity in which no single perspective is prioritised. An antidote to the endless stream of “clickbait” and “content”, this is journalism at its most honest and reflective – a multi-dimensional narrative about what it means to be a female journalist in the Arab world and in the West. Particular recognition must be afforded to Mariam Antar, who brilliantly translated three of the essays. With her help, Hankir shines a light on the strength of those who have reported on war and womanhood and invites us to “listen to what they have to say”. I urge you to accept her invitation. Sarah Collins

Zahra Hankir’s pioneering collection Our Women on the Ground (Harvill Secker) is required reading. With stories from Christine Amanpour, Chief International Anchor for CNN, to Ruqia Hussain, citizen journalist who reported from inside occupied Raqqa on Facebook, it disrupts traditional narratives surrounding conflict reporting and Arab women to perform an act of solidarity in which no single perspective is prioritised. An antidote to the endless stream of “clickbait” and “content”, this is journalism at its most honest and reflective – a multi-dimensional narrative about what it means to be a female journalist in the Arab world and in the West. Particular recognition must be afforded to Mariam Antar, who brilliantly translated three of the essays. With her help, Hankir shines a light on the strength of those who have reported on war and womanhood and invites us to “listen to what they have to say”. I urge you to accept her invitation. Sarah Collins

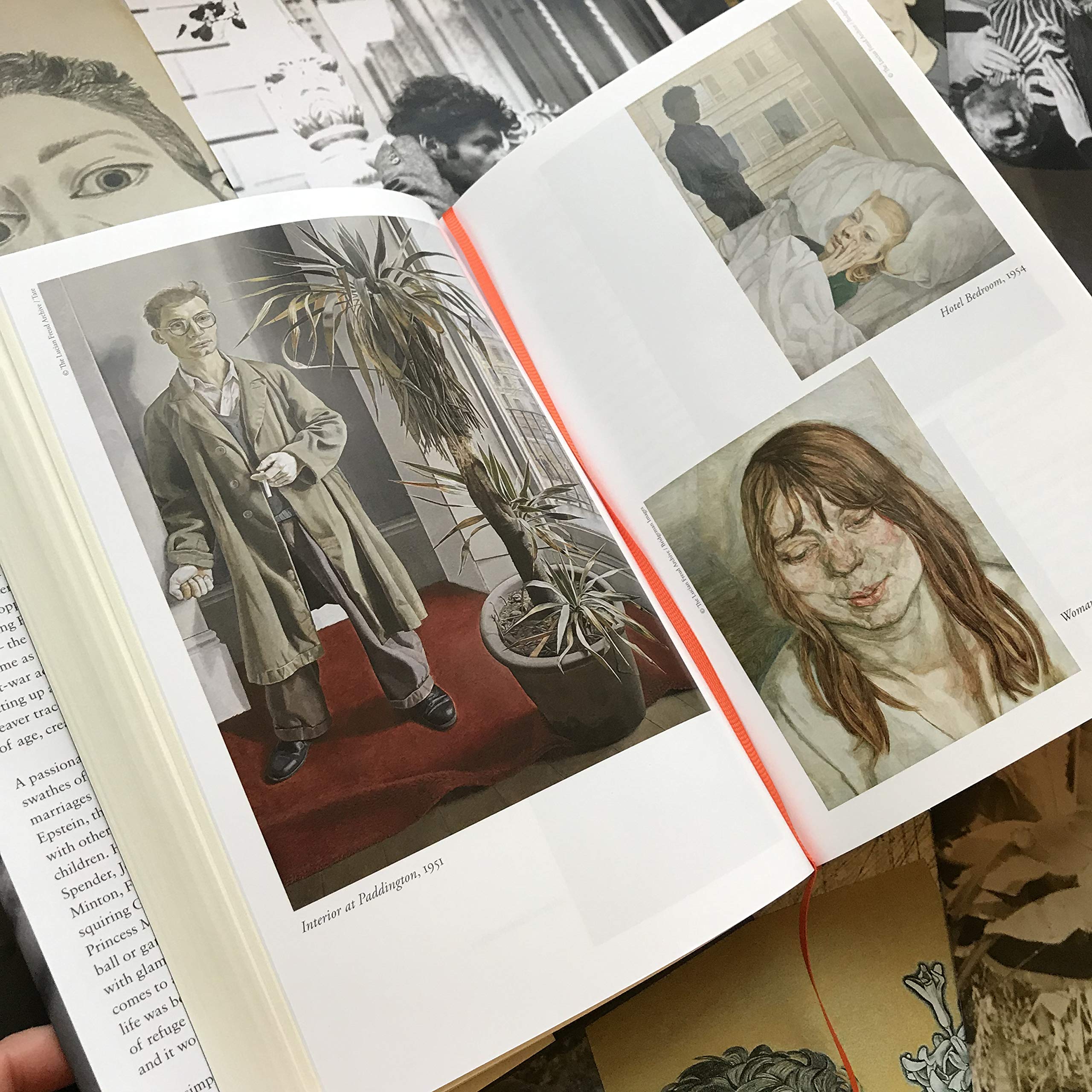

Two books offering different perspectives on Lucian Freud were my outstanding reads of 2019. The first volume of William Feaver's biography, The Lives of Lucian Freud (Bloomsbury) is as much about the friendship between author and subject as it is about Freud himself, and the dominance of Freud's voice, undiminished even from beyond the grave, is as convincing evidence as any of his bullying nature. Published almost concurrently, the Lucian Freud Herbarium (Prestel) is no less revealing, bringing together the artist's paintings and drawings of plants. Plants are often a prominent feature of Freud's portraits – who could forget the monstrously present yucca plant in "Interior in Paddington", 1951? But the most interesting works in this book are essentially studies, like the Still-life with Aloe, an oil painting from 1949. Here a herring lies next to an uprooted aloe vera plant: each tinged with green, the formal similarities between them are astonishing. And the herring is so much more dead than the plant, which raises itself slightly in a final bid for life. It's a painting that allows us insight into the quality and nature of Lucian Freud's looking, and through it to find pathos and subtlety in his portraits. Florence Hallett

Two books offering different perspectives on Lucian Freud were my outstanding reads of 2019. The first volume of William Feaver's biography, The Lives of Lucian Freud (Bloomsbury) is as much about the friendship between author and subject as it is about Freud himself, and the dominance of Freud's voice, undiminished even from beyond the grave, is as convincing evidence as any of his bullying nature. Published almost concurrently, the Lucian Freud Herbarium (Prestel) is no less revealing, bringing together the artist's paintings and drawings of plants. Plants are often a prominent feature of Freud's portraits – who could forget the monstrously present yucca plant in "Interior in Paddington", 1951? But the most interesting works in this book are essentially studies, like the Still-life with Aloe, an oil painting from 1949. Here a herring lies next to an uprooted aloe vera plant: each tinged with green, the formal similarities between them are astonishing. And the herring is so much more dead than the plant, which raises itself slightly in a final bid for life. It's a painting that allows us insight into the quality and nature of Lucian Freud's looking, and through it to find pathos and subtlety in his portraits. Florence Hallett

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment