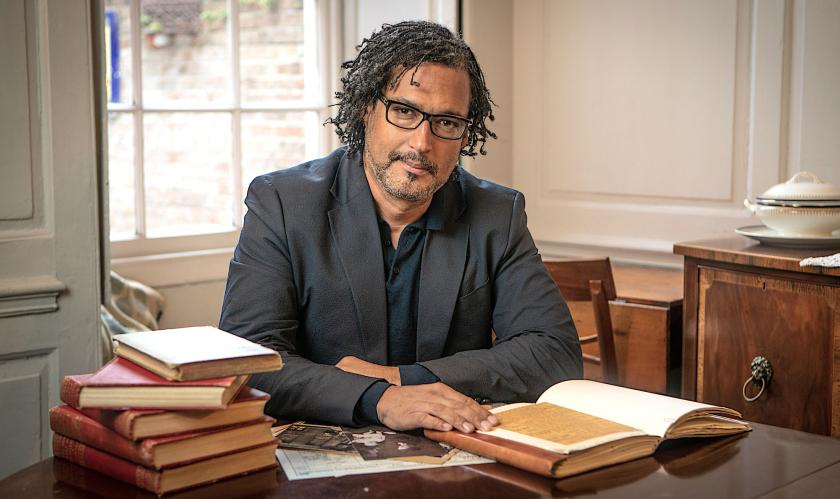

David Olusoga’s A House Through Time concept (BBC Two) has proved a popular hit, using a specific property as a keyhole through which to observe historical and social changes. After previously picking sites in Liverpool and Newcastle, this time he’s chosen Bristol, the city where he has lived for over 20 years.

Among Olusoga’s particular interests as a historian are the British empire, race and slavery, so it was no great surprise to find him homing on on Bristol’s links with the slave trade. His chosen house was built in 1718 by Captain Edmund Saunders, who trafficked slaves from Guinea on Africa’s west coast to the Caribbean. Hence the building’s address in Guinea Street.

Dripping with his ill-gotten wealth, Saunders built three houses and lived in Number 11, though 10 is the only one still standing, and this was occupied by another slaving captain, Joseph Smith. The diligent historian’s trawl through the Slave Voyages database found a reference to Smith buying 276 “human beings” in Nigeria for transatlantic shipment, a fragment of an eventful career in which his ship the Hambleton was captured and plundered twice by the same pirates. Encountering one of the pirates back in Bristol, Smith turned him in to the authorities (which Olusoga seemed to think was rather churlish of him), though an 11th-hour pardon spared him a hanging.

The house was a smart choice. Another highlight of its career was a spell of occupation by the political writer Dr John Shebbeare, who had the distinction of being satirised in a Hogarth drawing (this promoted Olusoga to pop in on Ian Hislop at Private Eye for a digression on political satire). The discovery of documents from the 1750s recording how a Jamaican man named Thomas ran away from the house gave Olusoga the chance to expatiate on the then-current fashion for keeping black servants “as fashion accessories”. Thomas’s owner was sugar trader Joseph Holbrook, whose wealth, we were sombrely reminded, was built “on the backs of enslaved Africans”.

After Holbrook’s death, anti-slavery campaigner John Wesley built a new Methodist chapel in Guinea Street. Olusoga surmised that Holbrook’s widow Hester must therefore have been forced to confront her morally-tainted fortune, though any evidence of this was not forthcoming. He’s a fine presenter with a gift for treating history with an accessible touch, but let’s hope Bristol’s sinister slaving past isn’t going to overshadow this entire series.

Add comment