Keiichiro Hirano: A Man review - the best kind of thriller | reviews, news & interviews

Keiichiro Hirano: A Man review - the best kind of thriller

Keiichiro Hirano: A Man review - the best kind of thriller

A conventional mystery plot unfolds into a profoundly reflective novel

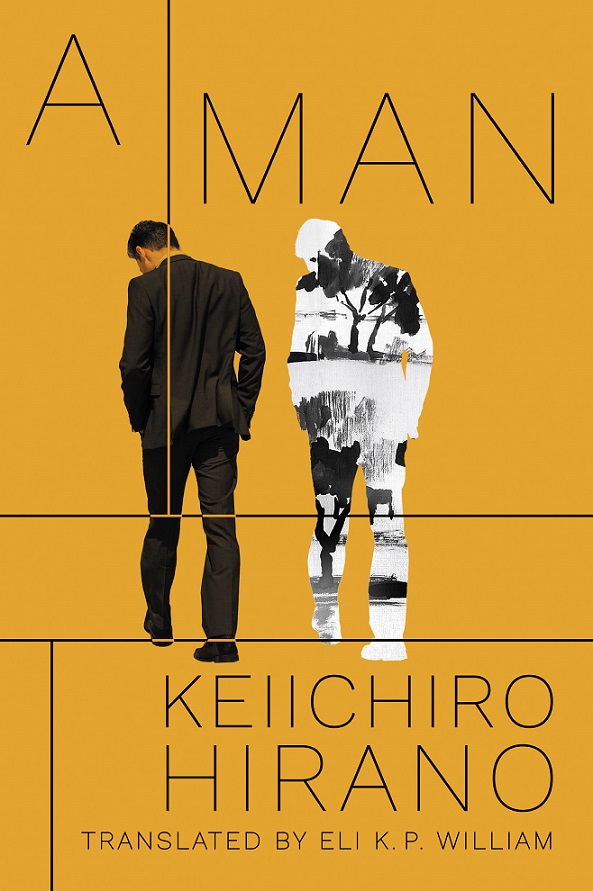

Keiichiro Hirano’s A Man has all the trappings of a gripping detective story: a bereaved wife, a dead man whose name belongs to someone else, mysterious coded letters, a lawyer intent on uncovering the truth.

A Man centres on the journey of Akira Kido, a middle-aged lawyer, to discover the identity of a man who, until his death, had been posing as a certain Daisuké Taniguchi. Kido searches, too, for the real Daisuké, but the more his investigations progress, the more he begins to reflect on his own frustrated life. This plot of double identities seems partly to draw inspiration from Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’s famous 1926 novella, The Story of Tomoda and Matsunaga, which explores in dramatic fashion the total reinvention of the individual. Yet, where Tanizaki uses the double life to picture the curious relationship between Japan and the West, Hirano finds an opportunity to look inward and interrogate the very workings of the self. With themes of racism and political controversy, and the spectre of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake looming large, A Man is a stubbornly modern, naturalistic exploration of the double identity theme and the philosophical musings it provokes.

Hirano uses the meticulous investigations of the lawyer Kido to throw into relief the insistent messiness of identity, both from a legal and philosophical perspective. The more the mystery reveals about the backstories of Daisuké and the man posing as Daisuké, the more blurred truth and deception become, until Kido can no longer be certain of the validity of either. The central message that our protagonist gleans, and that the author seems intent on conveying, is that just as much meaning can be extracted from a life founded upon lies as one that is completely "real". Deceit becomes attractive, even erotically charged at times, to the extent that the truth – which represents the ostensible goal of the mystery plot – no longer enjoys the nobility assigned to it by (among other things) the law. Where such novels often necessarily suffer something of an anti-climax at their revelatory dénouement, Hirano attests that the key mysteries of identity, truth and deceit remain unsolved.

Hirano uses the meticulous investigations of the lawyer Kido to throw into relief the insistent messiness of identity, both from a legal and philosophical perspective. The more the mystery reveals about the backstories of Daisuké and the man posing as Daisuké, the more blurred truth and deception become, until Kido can no longer be certain of the validity of either. The central message that our protagonist gleans, and that the author seems intent on conveying, is that just as much meaning can be extracted from a life founded upon lies as one that is completely "real". Deceit becomes attractive, even erotically charged at times, to the extent that the truth – which represents the ostensible goal of the mystery plot – no longer enjoys the nobility assigned to it by (among other things) the law. Where such novels often necessarily suffer something of an anti-climax at their revelatory dénouement, Hirano attests that the key mysteries of identity, truth and deceit remain unsolved.

The author deftly elevates these questions to the level of literary creation. In the care it takes to muddy the waters of identity, A Man simultaneously reflects on the practice of writing novels, asking whether the reinvention of individual identity is any less evocative than the noble "deceit" of fiction writing. What difference does it really make if a story is a fiction instead of the truth? Such a question is inherently linked with the Great East Japan Earthquake and its literary responses which, nine years on, are still in a state of flux. Hirano’s sustained blurring of truth and lies on both a personal and literary level is evidence that, as Haruki Murakami observes of literature’s treatment of the events in 2011, "the distinction hardly matters in the face of such a reality".

In light of the multi-layered nature of A Man, Eli K.P. William’s translation fails at times to capture the distinct feel of Hirano’s writing. This is, after all, a novel that draws on the specific cultural history of Japan and Japanese identity; the occasional presence of a highly westernised, colloquial vocabulary jars therefore with some of the most important concepts. For the most part, however, Hirano’s most poignant assertion is faithfully rendered. Fiction, A Man seems to argue, is a valuable source of solace despite – or, conversely, on account of – its status as a lie.

- A Man by Keiichiro Hirano trans. Eli K.P. William (Amazon Crossing, £8.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Add comment