Mieko Kawakami: Breasts and Eggs review - a book of two halves | reviews, news & interviews

Mieko Kawakami: Breasts and Eggs review - a book of two halves

Mieko Kawakami: Breasts and Eggs review - a book of two halves

Claustrophobia, queasiness, and self-discovery in the female body

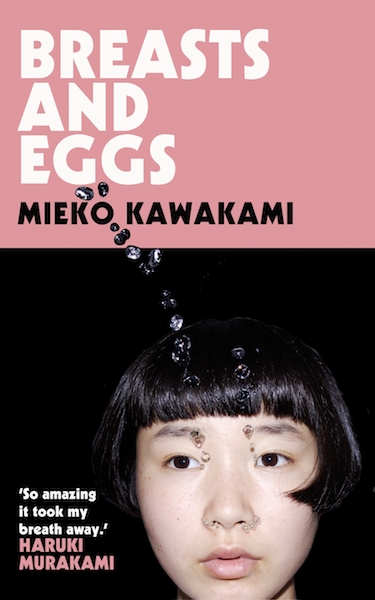

Mieko Kawakami’s Breasts and Eggs is a true novel of two halves and is (excuse the pun) a bit of a curate’s egg. Kawakami’s bio at the beginning of the text explains that the novel was expanded from an earlier novella, made clear by a separation into books one and two. The first book centres on the visit of the narrator’s sister and niece to her house in Tokyo, and the second brings the narrator, Natsume, into the centre of a story about her desire to conceive a child at forty.

The unifying factor between the two stories is not only the narrator but also a visceral body horror. The characters who pass through the text are often queasily and claustrophobically trapped within their own physicality. Natsume’s sister, Makiko, has visited Tokyo in order to have a breast enlargement, an uncomfortable parallel with their mother, who died of breast cancer at a similar age. Makiko’s obsession with her breasts is contrasted strongly with her almost incorporeal sister and her silent daughter, whose diary entries express her discomfort with puberty and womanhood. The feeling of claustrophobia is enhanced by the repetitiveness of the text itself, with obvious and close contrasts throughout. Someone describes the Russian doll of a book that Natsume herself has written at one point in a very apt way, both as rebirth but also something more trapping: “The world changes, the language changes, but they’re the same people, with the same souls. It keeps repeating forever…””.

The body in Breasts and Eggs is almost exclusively female. Most of the narratives are told by women, and all but one of the main characters is female. In the first half of the text, men are only there to be run away from, and in the second half, men only seem to exist as a means by which to provide sperm, but in an almost exclusively non-sexual context. When sex comes into it, it is almost horrific. It is a focus which gives the book as a whole its strength, allowing women to talk amongst themselves, navigating the policing of the female body by men and society as a whole in a space apart.

The body in Breasts and Eggs is almost exclusively female. Most of the narratives are told by women, and all but one of the main characters is female. In the first half of the text, men are only there to be run away from, and in the second half, men only seem to exist as a means by which to provide sperm, but in an almost exclusively non-sexual context. When sex comes into it, it is almost horrific. It is a focus which gives the book as a whole its strength, allowing women to talk amongst themselves, navigating the policing of the female body by men and society as a whole in a space apart.

When a man does enter Natsume’s world, he is the source of great questioning and worry, but he also has a contingency that allows for his story to enter the narrative but not become the focus. As one of the characters points out in the wry way that characters in Breasts and Eggs often express themselves, “'how could a man and a woman ever see eye to eye? It’s structurally impossible'”. It is a woman who forces Natsume into a sort of birth, a rupture to the relative tranquillity of her adult life. They have a deep and difficult conversation about children, after which Natsume feels that “it was like my skull cracked open. Something was gnawing at my insides”. Her resulting illness is the catalyst for the events that lead to an actual experience of childbirth. A man might have been involved, but only briefly. The novel gives birth, but never loses its sense of being the story of a woman’s body. The dislocations and dissociations along the way are sometimes jarring and feel like they don’t wholly work, but the unifying factor of the female body saves a book that feels as necessary as it is at times awkward.

- Breasts and Eggs by Mieko Kawakami (Pan Macmillan, £14.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Comments

Why on earth the English