10 Questions for novelist Mieko Kawakami | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for novelist Mieko Kawakami

10 Questions for novelist Mieko Kawakami

Assaying 'Heaven' - the Japanese writer on childhood, vulnerability, and violence as a complement to beauty

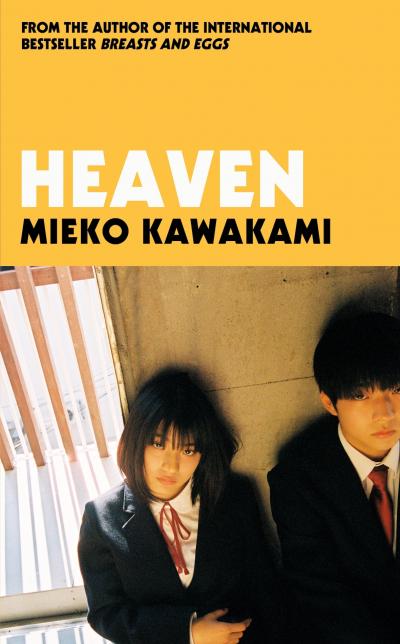

Mieko Kawakami sits firmly amongst the Japanese literati for her sharp and pensive depictions of life in contemporary Japan. Since the translation of Breasts and Eggs (2020), she has also become somewhat of an indie fiction icon in the UK, with her books receiving praise from Naoise Dolan, An Yu and Olivia Sudjic.

Taking inspiration from Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Kawakami calls into question the survival of the meek in a society that favours the strong, and underlines the disturbing callousness of youth. The violence of the novel sits starkly against its moments of unwavering kinship to evoke the fear, fragility and enduring hope of adolescence.

Originally published in 2009, the novel established Kawakami as a literary powerhouse in her native Japan. Heaven is grittier and more succinct than her other translated works, featuring moments of vivid physical and emotional cruelty. Yet the book retains Kawakami’s quietly contemplative style. I sat down with the author and her translator to talk about Heaven and her growing global popularity.

IZZY SMITH: In Heaven, the two young characters suffer greatly at the hands of their peers. You explore similar struggles in Breast and Eggs with the character of Midoriko there who chooses to be mute rather than express her distress. What draws you to writing about the pain and confusion of young people, in particular?

MIEKO KAWAKAMI: When it comes to the period of life that is childhood, there are certain universal conditions. There is a kind of oppression that is shared by everybody. This is something that we have all been through. And so I think that, there is a light trauma that everybody has at the foundation of childhood, that cannot be separated from who we are now. So if we write about youth, we are also writing about the whole of life. I think that our childhood or teenage years – that time is the essence of the sadness and suffering of life. That's the reason that I write. That is what I hope to express.

You’ve now had several books translated into English, and translated fiction is becoming increasingly popular for readers in the UK. How do you feel about your writing being translated into such a different language?

You’ve now had several books translated into English, and translated fiction is becoming increasingly popular for readers in the UK. How do you feel about your writing being translated into such a different language?

In Japan, reading literature through translation is very common. I personally have read many books in translation. But when it was suddenly my words being translated and read in another language, I was quite surprised by many parts of that process: I found that Japanese and English are completely different languages, so the product is also something completely different, too. But there is the same message. The same story is being conveyed.

If we take Finnegan's Wake by James Joyce, for example, that’s something I can only read in Japanese translation. There's a lot of quite strange and difficult expressions in a work like that. The book contains so many words that are unfamiliar or were invented by him entirely. For me, the translation is like no other Japanese novel. So, of course, there is no way of ascertaining those emotions directly, but what is important in translation is that it captures those dreams, those prayers, and the desires of the characters.

I've never lived outside of Japan. I was born and raised here in Japan, but through this process of my own work being translated, it reminded me indirectly that I speak a minority language.

Writing about outcast characters is a common thread in your writing. In Heaven, your protagonist is subject to violent bullying for his lazy eye, at the hands of other unforgiving teens. Why do you think you are drawn to marginalised voices such as his?

Whether it's in Heaven, or in my other works, I don't necessarily approach writing the characters as wanting to give a voice to someone who's in the minority. Instead, when I'm looking at writing that individual person, these moments of suffering come naturally as part of life, and their marginalisation becomes part of them as well. I think we have a tendency to categorise people as strong or weak, but I think that weakness is really what's at the core of, or a fundamental part of humanity.

Everybody is born as a powerless infant, and then they pass away in a similar position of vulnerability. So, writing about people in these weaker positions means portraying both a former and a future self. When I set out to write my novels, this becomes part of the characters and who they are.

In Heaven, you describe Kojima, the young girl who is bullied alongside your protagonist, as having “a voice like a 6B pencil”. The book is scattered with these metaphors that really evoke the innocence of our teenage years. How did you set out to capture the tone of youth so vividly?

When I began writing, I started with poetry. I think that writing poetry gives movement to what's beautiful in the world and allows a writer to portray that in different hues. When I set out to write Heaven I really thought about the senses, particularly vision. I wanted to write about how what we see when we’re young is always changing and how this allows us to constantly enter and re-encounter new worlds. I enjoy thinking about how to express that overwhelming beauty that is inside humans. I think that's really what poetry sets us up to do. Now, when I write prose, that's something that's always present and something that was particularly important when writing the characters in Heaven.

The violence in the novel is brutal and unnerving. Do you find that the beauty of life is only most vivid when held up against such violence?

With things like pain and relief, or “good” and “bad”, I think we're always taught to look at these as opposites. In order to pursue happiness, I think there needs to be a sacrifice. This means embracing both the good and the bad. I do think that pain or sadness especially instills a kind of wisdom in life. I think through my own experience of these kinds of negative and positive circumstances, they bounce off each other and work almost like an app where they’re amplifying and increasing each other. However, at the same time, violence itself exists as violence. And the same can also be said for beauty existing independently.

There was real anticipation for Heaven reaching UK bookstores. How does it feel to be a revered name in literary circles, not just in Japan but worldwide?

I was really surprised to see it was at the top of weekly favourites in UK bookshops. I think I have my publicist to thank! Also, we are now so connected online, I get young people sending me different things on social media and connecting with the books. As a writer living in these particular times, I think it really makes me feel a connection with my readership.

Novels and literature have a varied importance or priority in different people's lives. I’m someone who came from the street, so for me, novels aren’t a luxury or a hobby. I learnt that reading and writing is such an important part of life, and an escape. I think that's probably shared by many of my readers. I really hope that my words and my books can reach these kinds of readers who are going through difficult challenges. I really hope that one day they’ll be able to say, “I used to read those books so much, but I don't need them anymore.”

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment