Ian Holm, British film's best supporting actor | reviews, news & interviews

Ian Holm, British film's best supporting actor

Ian Holm, British film's best supporting actor

From King Lear to Bilbo Baggins - remembering the great film actor who vanquished stage fright

Ian Holm was once in his local cinema on High Street Kensington, enquiring at the ticket office about concessions for people who appeared in the film they wished to see. The unlucky vendor failed to make the connection between the short customer with full beard and the clean-shaven priest in the sci-fi caper showing on Screen Four upstairs. He had to make an internal call to the manager. "There's someone here who says he's in The Fifth Element. Wants a discount." "Oh yeah.

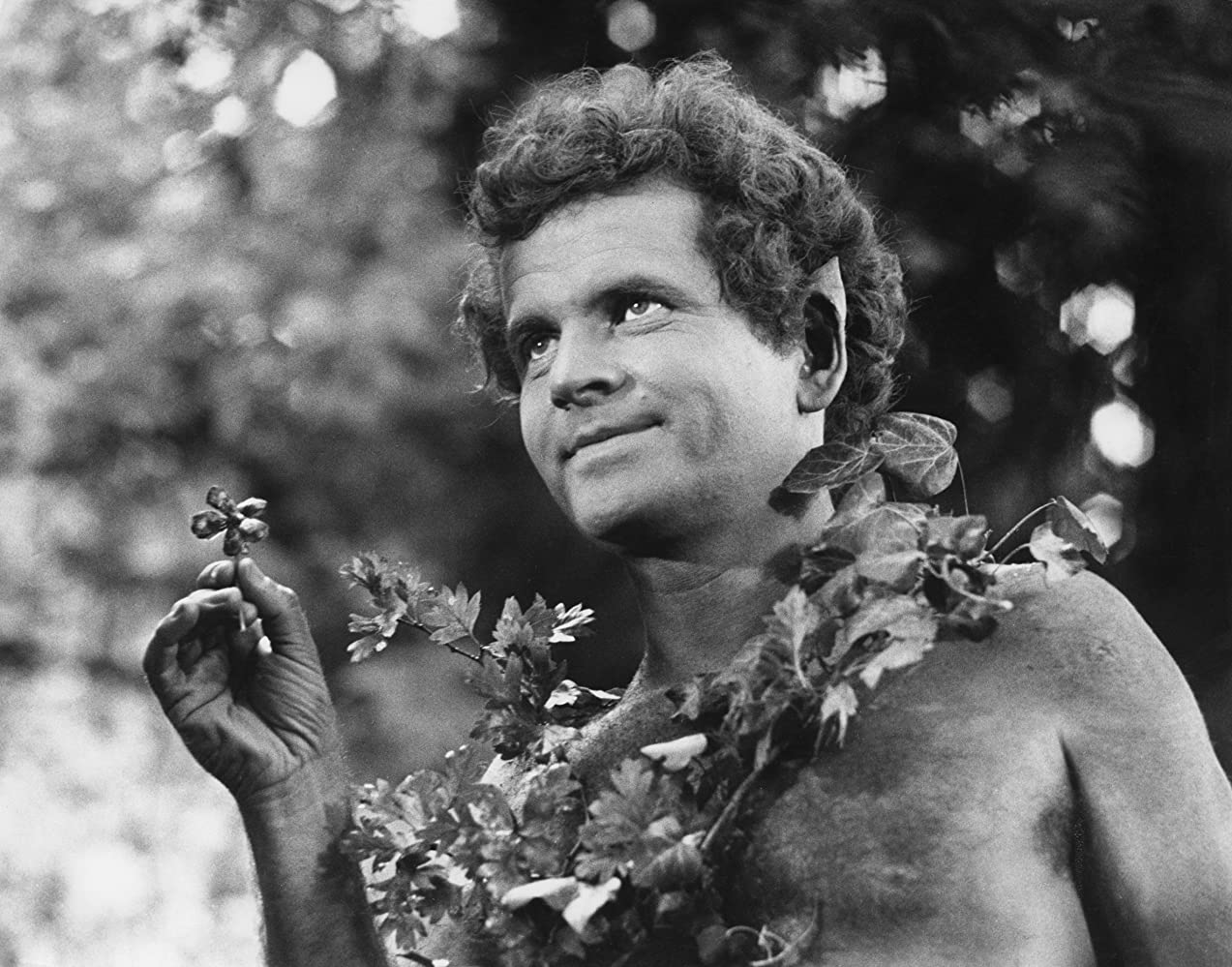

Holm, who has died at the age of 88, became a prolific screen actor partly because he was prepared to appear in films he didn’t expect to like. "If you've got more than one scene,” he explained, “unless the film is absolute rubbish you would be hard put as a good actor not to be able to do something with it. And that's always what I look for. Can I do something with this seemingly very ordinary-looking part? And if I think I can, if it's got a scene... As Jimmy Stewart said, movies are about moments, and that is so right. If you've got a scene with one moment, that's great, you work towards that." There were a handful of momentless movies which sit four-square and ineradicable on his CV. Peter Hall's A Midsummer Night's Dream (pictured above) was "a total disaster. For some reasons he didn't want to worry about continuity. Which tended to make it rather difficult." Wilbur Smith's Boer War blockbuster Shout at the Devil "came at a time in my life when it was a very good plan to be 8,000 miles away. It was a domestic situation." (Second marriage, end of.) But he volunteered March or Die with Gene Hackman as the absolute pits: "That was an appalling experience."

There were a handful of momentless movies which sit four-square and ineradicable on his CV. Peter Hall's A Midsummer Night's Dream (pictured above) was "a total disaster. For some reasons he didn't want to worry about continuity. Which tended to make it rather difficult." Wilbur Smith's Boer War blockbuster Shout at the Devil "came at a time in my life when it was a very good plan to be 8,000 miles away. It was a domestic situation." (Second marriage, end of.) But he volunteered March or Die with Gene Hackman as the absolute pits: "That was an appalling experience."

Ian Holm was fairly constantly employed as a screen actor since he was plucked from the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1967 to appear with Dirk Bogarde and Alan Bates in John Frankenheimer's The Fixer. But the most famous thing about him was the stage fright that pounced in 1976. He returned to theatre opposite his third wife Penelope Wilton in Harold Pinter's Moonlight in 1992 and has vanquished the demons triumphantly in Richard Eyre's studio production of King Lear in the National's Cottesloe Theatre. While he compensated for his absence from the theatre with ubiquity on screen, he rarely appeared at the top of a movie bill. He was always a movie's tasty side order, rather than the main dish, "also starring" in Alien, Dance with a Stranger, Chariots of Fire (his wily coach Sam Mussabini won an Oscar nomination), The Madness of King George, Greystoke, Big Night, Night Falls on Manhattan, A Life Less Ordinary and, most visibly of all, as Bilbo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings (pictured above). These were all Holm-sized roles, small but notable, like Holm himself.

While he compensated for his absence from the theatre with ubiquity on screen, he rarely appeared at the top of a movie bill. He was always a movie's tasty side order, rather than the main dish, "also starring" in Alien, Dance with a Stranger, Chariots of Fire (his wily coach Sam Mussabini won an Oscar nomination), The Madness of King George, Greystoke, Big Night, Night Falls on Manhattan, A Life Less Ordinary and, most visibly of all, as Bilbo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings (pictured above). These were all Holm-sized roles, small but notable, like Holm himself.

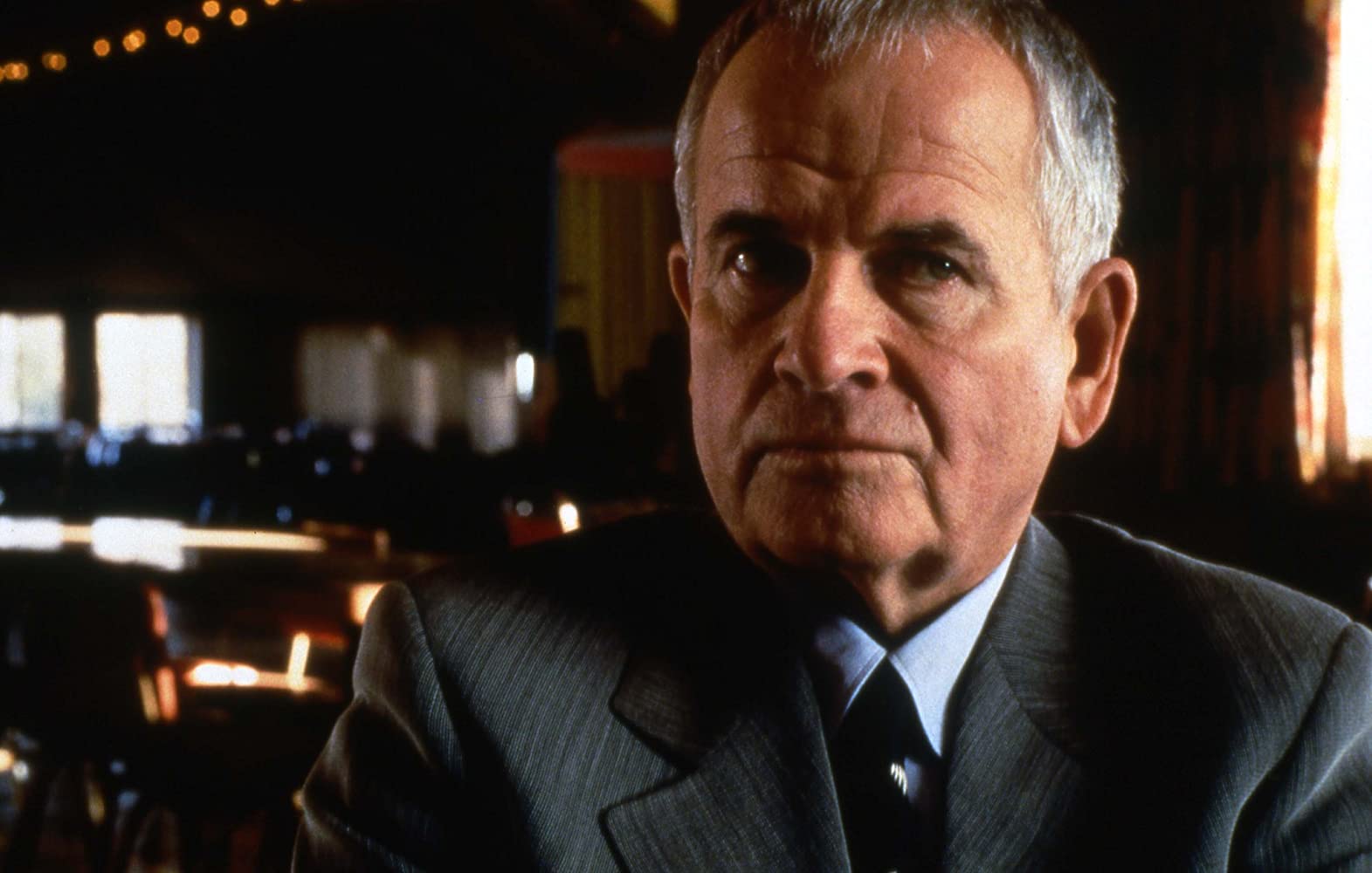

He wasn’t asked to carry a movie until Atom Egoyan's The Sweet Hereafter (pictured below), adapted from the novel by Russell Banks, about a filibustering attorney who descends on a remote Canadian community to seek justice for the parents of the local children killed in a school bus accident. The role was tailor-made for Holm's ineffably doomy face. In an immensely subtle performance, every wrinkle that time had chiselled into his physiognomy was made to pull its weight, every trademark twitch and muscular tic to speak of his immense burden of sadness.

Holm worried that his face was in fact too expressive. "With directors I know and love I just say, 'Please, please, please watch the tics.' Through nerves or whatever my face becomes very pliable. As you get older you start to cover up vocal instability or whatever with much more facial reaction. And also an innate desire to portray original thought." It was an attribute that sat well with the listening roles he found himself playing. Unlike many actors, he had a virtuosity that was as apparent when someone else was talking. He got technical help in this area from Lee Marvin, which was why he had fondish memories of Shout at the Devil. "He was one of the greatest pros I've ever worked with. On my first day, nervous and shaking and sad to be away from home, I had this silly scene putting up this flag. Marvin had his close-up and then it was my close-up and everybody left except Marvin, who said `I'll give you a hinge line here.' I said, `Sorry?' He said, `You don't know what the fuck a hinge line is, do you? I'll play a scene for you off camera and that should give you something to react to.' Amazing, and he did. I thought that was extraordinarily generous."

He got technical help in this area from Lee Marvin, which was why he had fondish memories of Shout at the Devil. "He was one of the greatest pros I've ever worked with. On my first day, nervous and shaking and sad to be away from home, I had this silly scene putting up this flag. Marvin had his close-up and then it was my close-up and everybody left except Marvin, who said `I'll give you a hinge line here.' I said, `Sorry?' He said, `You don't know what the fuck a hinge line is, do you? I'll play a scene for you off camera and that should give you something to react to.' Amazing, and he did. I thought that was extraordinarily generous."

Holm trained his features to accept the lens's proximity. His best moment in Big Night was not when he was filling the screen with pneumatic Italian bonhomie, but in his last scene, when he stood accused of ruining his neighbouring restaurateurs. With no pay-off line, he bowed out with a beautifully judged shrug of the mouth. Kenneth Branagh said in his autobiography that Holm is "very much of the anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-less-of school of acting." "Which I've always regarded as a compliment," he said.

His father worked in a psychiatric hospital in West Ham. When Hom was still a boy they moved to Devon, then on to moribund post-war Worthing. "The only film I remember vividly was my father taking me to see the original Les Misérables with Charles Laughton. I can remember seeing that in about 1938." Holm was subsequently Ariel to Laughton's Prospero in Stratford. He spent formative years on his own going to the Dome in Worthing. But after RADA, then the RSC, he didn't cross the rubicon into film until he was 35, past the age for juvenile leads.

He took to the immersive demands of film acting and managed a commanding array of accents. His Irish cop from Queens in Sidney Lumet's Night Falls on Manhattan was a particularly detailed study of gum-chewing vowel-mangling. After shooting a big court scene "a lot of the locals who were extras said, `That is a flawless accent. We would really think that you came from Queens.'" But his commitment to verisimilitude had its limits. He was invited out on police patrol with the cops by the actor playing his partner. "You have to sign a form saying `If you get shot, it's not our fault.' He said, 'You wanna go out, Ian?' I said, `I don't think it's really my scene.'”

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment