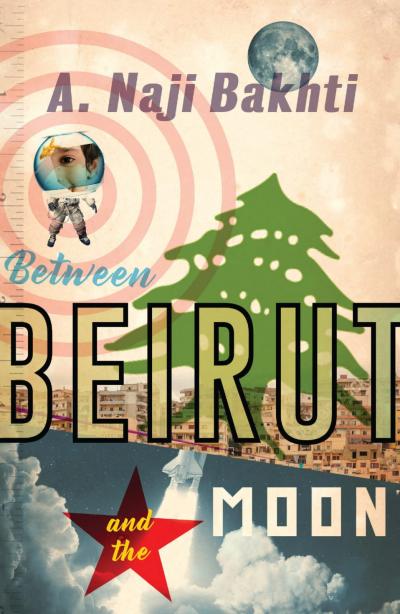

A Naji Bakti: Between Beirut and the Moon review - a seriously comical coming of age | reviews, news & interviews

A. Naji Bakti: Between Beirut and the Moon review - a seriously comical coming of age

A. Naji Bakti: Between Beirut and the Moon review - a seriously comical coming of age

Often hilarious search for identity in Lebanon's complex capital

What stands between Beirut and the moon? Between Lebanon’s capital and the limitless possibility beyond? It is a question as complex and immense as the nation itself. In the wake of the devastating explosion on 4 August, as well as longstanding government corruption and an unprecedented economic crash, it feels, now more than ever, as though the answer is: everything.

The beauty of A. Naji Bakhti’s Between Beirut and the Moon is that it refuses to take the easy route. It embraces the city’s paradoxes and complexities, acknowledges its defects and limitations, and celebrates its freedoms and joys. Our narrator Adam’s life is undoubtedly shaped by the hardships of social and political instability, but his is also an often hilarious journey through coming of age in Lebanon’s vibrant, historic and much-loved capital. Between Beirut and the Moon is as much about drinking Almaza beer on the beach, and navigating the universal stumbling blocks of adolescence, as it is about sheltering from Israeli bombs in the family bathroom.

Adam dreams of going to the moon. We discover this on the book’s first page. Only a page later, we feel the first swift sting of his quashed dreams in his father’s ridicule: “Don’t be ridiculous […] who ever heard of an Arab on the moon?”. And while in principle, this might seem harsh, callous and even offensive, it becomes clear as the story progresses that there is an uncomfortable truth to Mr Najjar’s words. Adam’s Lebanon will not make him an astronaut.

In interviews, A. Naji Bakhti has spoken about “The idea that there is always a better Lebanon somewhere, that we’re all aching to see and hoping to reach”. This intangible dream drives each of the characters in the story in a different way: it feeds Adam’s father’s hungry appetite for Lebanese literature, and his search to pin down Lebanon’s expansive culture and history. It fuels the rhetoric of Basil, Adam’s best-friend-turned-recruit to the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, who sees his role in the SSNP as an investment in the future of the nation and his generation. Perhaps this “better Lebanon” is a country where a young boy like Adam would not just dream of being an astronaut: it’s a country where he could actually be one. Or maybe even one where he would never have felt the tug of such extreme escapism. As the book progresses, Adam’s attentions turn further away from the moon, and increasingly towards his friends’ and peers’ gradual emigration – each one a tacit question posed against his own decision to remain.

Still, Between Beirut and the Moon is not all struggle, and its real strength lies in Bakhti’s skill for comedy. Adam’s family home is held up by hoarded books: teetering piles which stand vertiginously amongst furniture and people. The books are so ubiquitous, and their volume so great, that they become confused with the actual structure of the apartment; they mock the solid walls and floors with a slapstick precarity. Adam’s family wage a constant battle against impending doom under a poorly balanced pile of books: in the post-civil war Beirut of this family home, it is books, not bombs, which pose a daily threat to Adam’s physical health.

Bakhti has also mastered the art of quippy conversation on the page. There’s the asinine one-upmanship of Adam and his jibing teenage cohort. Even better, Adam’s parents’ exacerbation at having to deal with the stupidity of their teenage offspring. In one particularly foolish escapade, Adam fakes sex with a girl from school in the toilets of a public bar. His mortified parents discuss his idiocy with pointed mockery of their culprit child. His mother begins:

“He nearly got his genitals chopped off.”

“It’s all part of his grand plan. Somehow this is all part of the road to becoming an astronaut. Isn’t it, son? That’s why he punches people, lashes his sister with my belt, and has sex in public toilets,” […]

“Pretend-sex,” I said.

“Jesus-Mohammed-Christ, I wouldn’t boast about that if I were you…”

The passage is just one of many in which I found myself laughing out loud, aided inevitably by Mr Najjar’s favourite perfectly balanced blaspheme: Jesus-Mohammed-Christ.

It’s a telling outburst. Adam, who is born to a Christian mother and a Muslim father, straddles multiple identities, landing somewhere and nowhere in the midst of them. Bakhti repeatedly addresses this sense of splitness through comedy. At school, Adam’s friend Mohammad devises a prank, asking his friends to pick: “Christian or Muslim?”. When someone answers “Christian” they get a slap – their Christian beliefs forbid them from slapping back. Adam, even before clocking the trick, realises that he doesn’t know how to answer.

What’s more, he’s unsure that he agrees with the very premise of the game:

It was true that my mother had never made to slap me […] but it was also true that the sole of her shoe had narrowly missed the tip of my nose and the top of my head on countless occasions. […] My mother may have been Christian but her shoe, almost definitely, was not Christian.

These comical narrative insights are indicative of Adam’s serious search to understand how he fits into the tick-box logic of religious identity. In the end, Adam arbitrarily picks Muslim: he prefers the Arabic word for Muslim to that for Christian.

Bakhti’s Between Beirut and the Moon tells of a search for identity in the mire of adolescence, religious factionism and post-war ambition. The comic is serious, and the serious is comic. Overall, it is a thoroughly entertaining, enjoyable and fresh read.

- Between Beirut and the Moon by A. Naji Bakhti (Influx Press, £9.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment