10 Questions for Poet and Critic Rebecca Tamás | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Poet and Critic Rebecca Tamás

10 Questions for Poet and Critic Rebecca Tamás

On 'Strangers' and the urgent interconnectedness of the human and non-human

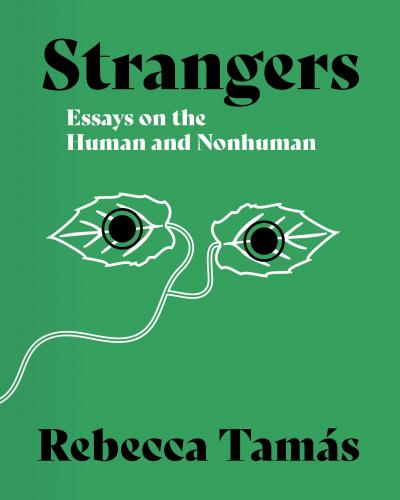

Strangers: Essays on the Human and Nonhuman is a powerful invitation to rethink, to doubt and to engage. Beginning among the Diggers’ tilled earth in 1649 and the eco-socialist "watermelon" juices that soil still stirs, the book makes an urgent argument for recognising our uneasy intimacy with the nonhuman.

JESSICA PAYN: The essays in the collection follow an ecological logic: they are at once deeply intimate with yet discrete from one another, so that the parts become greater than the whole. I’m interested in how the project grew. "On Grief" and "On Watermelon" were both previously published. When and why were the other essays written? At what point did you decide to bring these writings together?

REBECCA TAMAS: All of these essays were written before any one of them was published. The project definitely grew holistically; I wrote them knowing I wanted them to interrelate and respond to each other. To me these essays are different limbs of the same creature, different responses to the same questions – questions of environmental equality, ecological thought and nonhuman intimacy. I turned to prose when I felt that poetry couldn’t, in this instance, offer the kind of directly addressed relationship I wanted with the reader about these themes.

JP. Strangeness is hugely important to the book: an outsiderness which is actually both within and without, and which becomes more mysterious the more it is known. Underpinned by an understanding of being as fundamentally relational, the strange acknowledges boundaries as radically open and porous. You write in the collection of the difference between knowing “factually, that human beings depend wholly on an interconnected web of human and nonhuman actors and things” and living this truth. How do you inhabit this very different mode? How do you live with strangeness?

JP. Strangeness is hugely important to the book: an outsiderness which is actually both within and without, and which becomes more mysterious the more it is known. Underpinned by an understanding of being as fundamentally relational, the strange acknowledges boundaries as radically open and porous. You write in the collection of the difference between knowing “factually, that human beings depend wholly on an interconnected web of human and nonhuman actors and things” and living this truth. How do you inhabit this very different mode? How do you live with strangeness?

RT. I think part of what is crucial to me in accessing this mode, in living with strangeness, is finding ways to constantly remind oneself that this is the true mode of existence. So that could be thinking about the gut bacteria that have a huge relationship to our health; it could be considering where our food comes from and how it was grown; it could be learning about how the insects crawling in the mud support the biodiversity that allows the environments we love to exist. Whatever we can do to always draw our own attention back to the web of human and nonhuman life is, I think, important in recognising our porous boundaries and our intimacy with strangeness. But everything within Western capitalism wants us to ignore or repress this, which is why it is a repeated practice rather than a single thought act. We need to keep taking ourselves back to the strangeness in which we exist, and that movement back to the strange is one that doesn’t end.

JP. There’s a wonderful exploration of Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta’s films and photographs in the essay "On Greenness" – how her “earth art” captures a fierce and sensuous becomingness with the nonhuman. At the end you write, “Her art shows us that the ‘natural world’ does not wait outside of us, but moves through the door of our being, connecting and reforming what we are, its sticky difference impossible to excise.” Could you talk about the inverted commas around "natural world", the discomfort with that phrasing?

RT. My issue with phrases like "the natural world" and "nature", and the reason I put inverted commas around them, is the way they suggest a clear demarcation between what is natural and what is human. It’s important to my environmental politics to remember that humans are animals; that we are part of nature; and that separating us from that fact is one of the structural actions capitalism takes to cut us off from the interconnected web of being that we exist in. So I use "the nonhuman", which isn’t a perfect phrase, but it’s one that has more truth to me – it simply means that which isn’t human, rather than suggesting that there is any profound rupture between what is natural and what is of us.

JP. What does the weird mean to you? I’m asking this in the context of the weird being connected with, but different to, strangeness. Both deal in unfamiliarity and discomfort: the gap between what is known or expected, and what is. But where strangeness is etymologically bound up with land and place (from the French étranger), the weird is related to magical thinking and fate (Macbeth’s Weïrd Sisters). How would you say ecological thinking and the occult are related?

RT. To me, to think ecologically means to be able to think somewhat outside of, or beyond, rigid rationality. By that I mean no rejection of science or knowledge, but it seems to be that to genuinely connect with the radical difference of the nonhuman means entering the kind of "Negative Capability" Keats described – a recognition that whatever knowledge you build about the nonhuman, it will never be total. That difference, that weirdness, will always be there, and you can never break through it – but you have to love it, relate to it, respect and let it live anyway. That is the true weirdness of ecological thought – the intimacy with, the reliance on, the closeness to, what is not you and can never be you. This, to me, links to the way in which the occult also explores non-rational spaces – spaces of emotion, mysticism, bodily change and weird power. These spaces are often degraded and denigrated, but they can be very potent locations for personal and spiritual growth and change. The occult is a space of "Negative Capability", where we are open to whatever kind of knowledge comes our way, an openness we must mimic in our relations to the nonhuman – avoiding deciding what we will learn before we’ve learnt it. Ecological thinking and the occult are both forms of thought that learn, that know, through doubt, through reaching towards what we can never fully contain.

JP. "On Pain" keenly explores “the suffering of exploited [women/animal] bodies under patriarchal capitalism” through a reading of Ariana Reines’ poetry collection The Cow. You write that her work “shows us what the real cost of body-as-meat is”. As your discussion shows, "meat" is an untidy category; it spans that which is fleshy, desired, denied agency and exploited. When do bodies become meat?

RT. To me, bodies become meat when they are devalued – considered only for the pleasure or satisfaction of others, rather than for their own agency. I don’t think that "meat" is a helpful category for the animals we eat either – they should remain pigs, sheep, cows when we eat them, not "meat" and not "pork". To know that they had a life of their own is an act of respect and of recognition: there is more out there than just us. What we desire with meat is pleasure without recognition of the consequences. When human flesh, often female identified, becomes meat, it becomes that which exists not for itself, which is there to be used, consumed, enjoyed. The agency of the human being, their original life force and mind, is silenced and transformed into a product. That is when a body is turned into meat.

JP. The plural is an insistent mode of address throughout these essays, particularly at their close: "we", "our", and "us" are used carefully such that they invoke collective human experience confronting the nonhuman “that rubs up against and inside us”. What do you think of Timothy Morton’s observation that pronouns are complex in an ecological age – “how many beings do we gather together and are they all human?” Do you think acknowledging this is a part of what an etiquette or "hospitality" towards nonhumans might look like?

RT. I certainly agree with Morton on that, and I think that trying to find ways to represent the difference of human and nonhumans in our language is a crucial step of hospitality. I don’t think I’ve solved this yet in my own writing. Should beings which move between "sexes" as some plants or bacteria do have their own pronouns, yet to be spoken by us? Should we be the ones to invent them? Is it better to use "our" pronouns, to remind ourselves that any naming we do of the nonhuman is contingent? I don’t yet have answers to these questions, but I think the idea of attempting to be hospitable in our language of nonhuman beings and worlds is crucially important – it is an important challenge for all of us.

JP. In the concluding essay, "On Mystery", you draw attention to “unspeakable meaning”: mystery as the failure of language. Elsewhere, you have described poetry as “language that can hold knowledge and unknowing in balance, that can use language to go outside of the meanings language allows.” If the essay form is less suited to this (less open, less ambiguous), what potentials does it also offer?

JP. In the concluding essay, "On Mystery", you draw attention to “unspeakable meaning”: mystery as the failure of language. Elsewhere, you have described poetry as “language that can hold knowledge and unknowing in balance, that can use language to go outside of the meanings language allows.” If the essay form is less suited to this (less open, less ambiguous), what potentials does it also offer?

RT. I think that poetic language is better suited to ambiguous, open meanings – which is why I love it and will always write it. I did try and bring some of that poetic sensibility into these essays, and that was part of my attempt to innovate the form, crack it open and play with its potential. Despite that, it is inevitably more "direct" in its arguments, and that felt crucial for the points I wanted to make. Partly I wanted to synthesise so much of the phenomenal ecocritical academic writing I’ve interacted with, and open it to a more personal, emotional and accessible reading. Prose felt more suited to saying what I knew I wanted to say, rather than finding out what I wanted to say. Poetry is better for the latter.

JP. The pandemic has meant a radical redefining of our relationship with, and closeness to, human others. In the sticky mesh of ecology, this also means changes for our relations with nonhuman beings and things. In your own experience, how have increased isolation and social distancing put pressure on your interactions with the nonhuman?

RT. It’s definitely made those interactions more urgent – the gratitude I feel for the birds on my birdfeeder simply existing, living, beyond our specific crisis, is intense. It’s also made me even more aware of how much those interactions are crucial to my own wellbeing – the intimacy that I had with spring, in lockdown, when I had time to watch each minute change of bud and grass, was incredibly restorative at a painful time. On the other hand, it’s also underscored how dangerous our relationship is with the environment, and how troubled. Almost everyone in the UK seemed to be taking more of an interest in the nonhuman world during the pandemic, and yet this country is a massive polluter. A majority of voters voted for a party with little of value to say on climate change. So there’s a pressure in that cognitive dissonance, that desire to sentimentalise "nature" without defending it.

JP. A short question to finish – are you working on anything now?

RT. I have begun to work on poetry again after a long break, and I’m picking up (again!) on ecological ideas. The work seems to be taking shape as a poetry/lyric essay hybrid, but we will see where it takes me!

- Strangers: Essays on the Human and Nonhuman by Rebecca Tamás (Makina Books, £12.99)

- Read more book reviews and features on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment