Nina-Sophia Miralles: Glossy - debut author takes on Vogue and the Condé Nasties | reviews, news & interviews

Nina-Sophia Miralles: Glossy - debut author takes on Vogue and the Condé Nasties

Nina-Sophia Miralles: Glossy - debut author takes on Vogue and the Condé Nasties

Can Vogue survive? Its fascinating history may provide an answer

“Bringing out a luxury magazine in a blitzkrieg is rather like dressing for dinner in the jungle,” wrote Audrey Withers, editor of British Vogue, in December 1940. No slacking was allowed, even in the midst of an air raid.

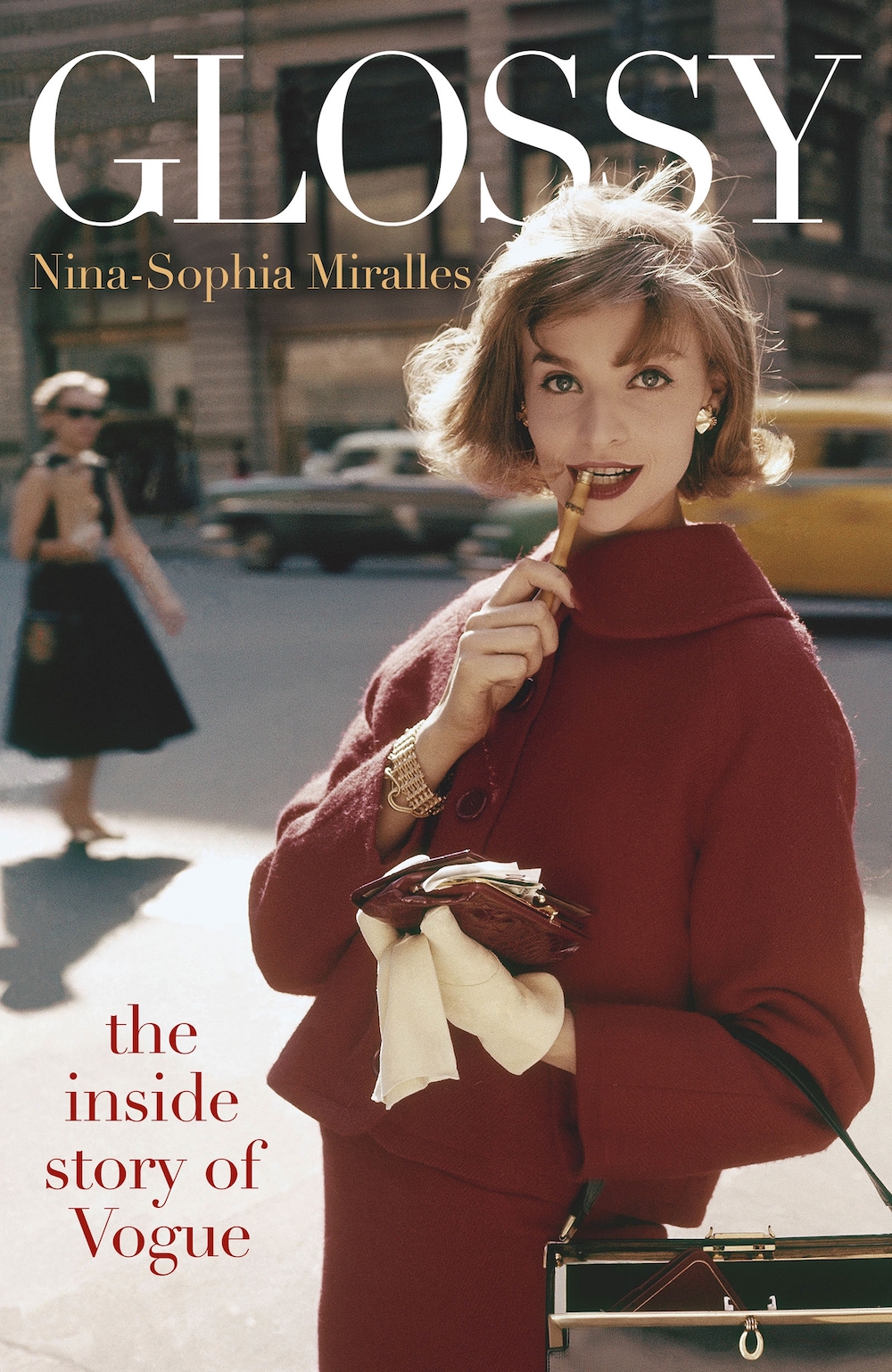

In Glossy: the Inside Story of Vogue, debut author Nina-Sophia Miralles takes on a formidable project: documenting the history of Vogue – she concentrates on the US, British and French magazines – from the first American issue (17 December 1892, 10 cents, a romantic illustration of a deb on the cover) under the ownership of Arthur Turnure to its present incarnations under editors Anna Wintour, Edward Enninful and Emmanuelle Alt.

Much of the book is riveting – there’s a fascinating picture of Dody Todd and Madge McHarg, a lesbian couple whose four-year stint as editor and fashion editor of British Vogue (Brogue) in the Twenties produced "an avant-garde masterpiece" before the disapproving Americans wielded the axe, and of the wartime years in Paris when editor Michel de Brunhoff saved Vogue from German encroachment – but oddly there’s no index and the endnotes are rather skimpy. And she sometimes comes out with startlingly wide-eyed millennial pronouncements. When explaining how the general strike of 1926 caused the media to fall silent because papers couldn't be published or distributed, she reminds us that, "In the days before the internet this left people completely disconnected." And in the early Sixties, "It was a hectic job being the editor before the internet."

But she races through the decades and the editors with impressive gusto. And as she says, “Vogue is not a subject people discuss freely – whether they are involved in Condé Nast or not.” Whether it can really be called an inside story is arguable. Not surprisingly, pictures are thin on the ground (rights and permissions would have been monumentally tricky to negotiate) and in-person interviews with Vogue insiders are few and far between.

Colombe Pringle is a notable exception. Editor of Vogue Paris from 1987 to 1994 (the only Vogue out of its 27 editions known by city rather than country, seeing itself self-centredly as the capital of fashion and the home of haute couture), she broke new ground by putting Barbara Hendricks, an African American opera singer, on the cover of the Christmas issue in 1987, figuring that "an accomplished and powerful black personality could serve as a sort of loophole to the unwritten ban on black cover stars". She also nabbed Nelson Mandela as guest editor in 1993. Designer brands were not appreciative and advertisers threatened to pull out. "I was very stubborn, " she tells Miralles. "You have to be." Soon after, Pringle was ousted.

This takes us back to another shameful episode involving Vogue Paris and the men in suits. When editor Edmonde Charles-Roux, a woman who saw fashion as an agent of social change rather than an art form, wanted to put African-American model Donyale Luna on the cover in 1966, the New York proprietors, Sam and Si Newhouse, were horrified and sent editorial director Alexander Liberman, who was a close friend of Charles-Roux when he lived in Paris, to talk her out of it.

“She refused to budge and so she was fired, a decision she unceremoniously heard only when she went to the accounts department to pick up her pay check and was informed it would be her final one.” Rather typical. Diana Vreeland was fired, also in a muffled manner, in 1971. “We’ve all known many White Russians, and we’ve known a few Red Russians. But Alex, you’re the only yellow Russian I’ve ever known,” she told Liberman.

The legendary Liberman was the art director – and artist – who discovered Irving Penn (he started out as Liberman’s assistant before he encouraged Penn to become a photographer). He assigned Lee Miller to cover Buchenwald concentration camp and commissioned many Cecil Beaton covers, featuring models in London bomb-sites. As editorial director he wielded vast power over Si Newhouse and was the dominant voice of Condé Nast from 1964 to 1994, when James Truman took over from him.

The legendary Liberman was the art director – and artist – who discovered Irving Penn (he started out as Liberman’s assistant before he encouraged Penn to become a photographer). He assigned Lee Miller to cover Buchenwald concentration camp and commissioned many Cecil Beaton covers, featuring models in London bomb-sites. As editorial director he wielded vast power over Si Newhouse and was the dominant voice of Condé Nast from 1964 to 1994, when James Truman took over from him.

To Grace Mirabella, editor of American Vogue from 1971 to 1988, Liberman was less than supportive. “Vogue readers are more interested in fashion than breast cancer,” he told her. “I’ve been a woman longer than you, and they’re interested in both,” she replied. When she pitched a piece on women’s evolving place in society, his response was: "You don’t need to do another story about working women. Women are cheap labour and always will be." True to form, when Anna Wintour finally achieved her goal of becoming editor of Vogue in 1988, the ousted Mirabella heard about it from her husband who’d just seen the news on TV.

Which brings us to those profligate years of the 1990s, when the Newhouse fortune was estimated at around $12 billion. Si Newhouse (Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown called him Emperor Augustus) was “the overlord, benefactor, the final word”. He would arrive in the office before dawn and walk around in his socks so no one could hear him. Editors could expect six-figure salaries as well as trips on Concorde, beauty treatments, clothing allowances of about $50,000 and feng-shui masters who re-arranged office furniture. The bottom line ruled. Adverts became advertorials and product placement sneaked into editorials.

Tina Brown and Wintour were constantly pitted against each other in the press. “But while Brown seemed like the clear front runner at Condé Nast, riding on the enormous success of Vanity Fair, she could not court Newhouse and Liberman with as much dexterity as Wintour could.”

And there she still is. In her fourth decade as editor-in-chief, the indomitable Anna Wintour is the second longest-serving editor after Edna Woolman Chase, who reigned at American Vogue from 1914 to 1952, while Alexandra Shulman, editor from 1992 to 2017, had the longest tenure of any in the London office.

Vogue, along with other fashion glossies, was slow to embrace the digital age. "A lack of understanding led to a half-baked product" and "numerous technical glitches made the user experience frustrating and unfriendly". Can it survive? The print business model has been decimated. Charges of racism and sexual misconduct in the fashion industry haven't helped. Hubbing, where editorial staff are cut back drastically and content is shared between publications, is now the norm. Fashion glossies – the ones that still survive in print form – look ever more interchangeable, and consequently there's a new audience for high-quality, independent – and expensive – niche magazines.

Condé Nast’s CEO Roger Lynch, ex-head of music-streaming service Pandora, is “the first appointment of an outsider in Condé Nast’s hundred-plus years. Lynch’s lack of publishing experience didn’t matter: his brief was to create a twenty-first century media company.” In this brave new world, Anna Wintour runs a membership programme charging $100,000 a year for access and invites to special events, while the Go Ask Anna video series allows real people (how unseemly) to "ask Anna Wintour how she really feels" about such matters as sneakers, hairstyles and Rihanna.

But Vogue may still be the last glossy standing. Edward Enninful, the first black, openly gay, male editor-in-chief, who took over from Shulman in 2017, has changed the conversation, though a somewhat sceptical Miralles is scathing about the Meghan Markle guest-editorship and says that Enninful "represents the new mainstream, a world where everything, especially fashion, has become highly politicised". She points out that he seems to prefer veteran photographers for his covers and that the only newcomer has been Nadine Ijewere, the first woman of colour to shoot a Vogue cover.

Vogue is a luxury, but that’s its strength. And its archive remains a priceless, peerless asset. Emmanuelle Alt wants her employees to understand this heritage. “I want the people around me to understand how lucky they are. You arrive every day and it's historic. There is no other magazine that can present that.” And in her thoroughly researched Glossy, Miralles has presented some of the evidence.

- Glossy: the Inside Story of Vogue by Nina-Sophia Miralles (Quercus, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment