The domestic realm has moved to the forefront of our lives in recent times. It’s been doing service as our place of work and our place of entertainment. Eating in has replaced eating out. Our hopes and dreams have been largely limited to what’s attainable within our four walls.

It’s probably fair to say that Ben Nicholson was a big fan of the domestic realm long before circumstances required the rest of us to re-think our relationship with it. When all the cups of tea and coffee one makes come out of one’s own kitchen and not the office canteen or a branch of Pret, we may find ourselves thinking anew about the objects that are the physical essence of daily living.

To that extent it was prescient of the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester to conceive of the exhibition of work by Nicholson now there, which runs until 24 October. Postponed no fewer than four times, Ben Nicholson: From the Studio – curated by Pallant House’s head of exhibitions Louise Weller – is a positive riot of mugs, jugs and glassware. It focuses on the importance of still life and the studio within Nicholson’s art, and goodness knows life has been pretty still for a long time now.

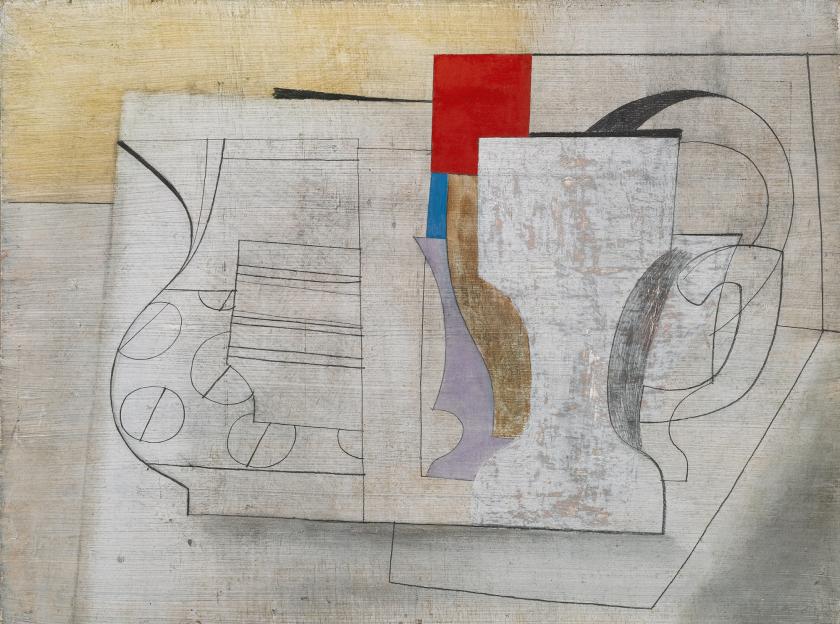

Nicholson was born in 1890, 18 years after Piet Mondrian, nine after Pablo Picasso and eight after Georges Braque. Of all Nicholson’s near contemporaries, it’s those three whose influence he felt the keenest, and he can be credited with playing a key role in introducing cubism to British art (main picture:Still Life, June 16 1947). But this lovely exhibition is a reminder that in terms of mood and emotion, Nicholson was very much his own artist. Feeling both British and European, there is a mutedness to his work but also a wonderful feel for colour and perspective.

The exhibition comprises more than 40 paintings, carved reliefs and works on paper alongside some of the still-life objects that inspired them. Foremost among the latter is an ample, horizontally striped ceramic jug, which we first encounter in a striking oil painting from early in Nicholson’s career – 1914 (the striped jug) – which is a homage, it would seem, to his artist father William.

An example of purely representational art, in spirit Victorian, with the jug dazzlingly lit, the work stands in stark contrast to the abstraction that Nicholson was soon to embrace and which remained his chosen style throughout his career.

It’s not hard to interpret the choice as a conscious effort to establish an artistic identity that broke from his father’s but at the same time those horizontal stripes seem to enter Nicholson’s soul. They recur right through to work he was producing towards the end of his life in the 1970s.

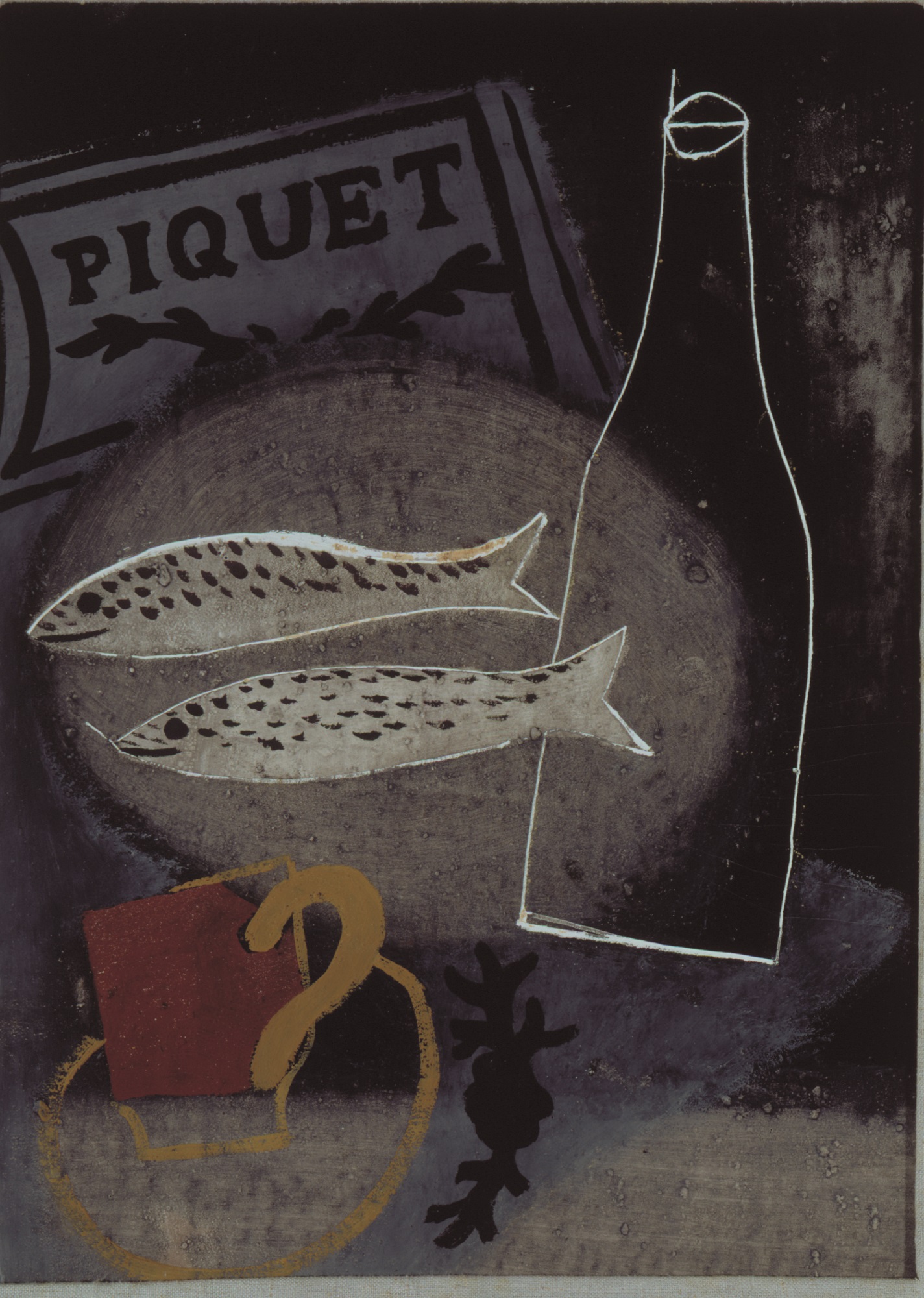

That the jug itself is on display – along with numerous other objects Nicholson liked to paint – is one of the exhibition’s great strengths. These quite mundane items of mostly kitchenware – but also a set of spanners, a table and draughtsman’s tools – allow us to experience Nicholson’s world and see these objects as he saw them, as a vehicle for expressing some profound ideas and feelings. There is both an intensity and a musicality to his arrangements, notably in 1933 (Piquet) (pictured above right), which depicts two fish served on a dish, a bottle and cup.

That work dates from the time of his marriage to Barbara Hepworth when they were part of a group of artists that in the 1930s helped give the Hampstead area of north London the reputation it enjoys to this day. In 1939 they went on to establish themselves as St Ives’s golden couple, and when they did so Nicholson’s pictures changed in one sense but not in another.

While his eye was naturally drawn to the sea, to the sky, to clifftops, to rooftops, to fishing boats, he somehow turned this subject matter into still lifes, flattening perspectives in the manner of Alfred Wallis. The delight that Nicholson takes in the shapes that St Ives offers is palpable.

Hepworth was the second of Nicholson’s three wives. He had previously been married to Winifred (nee Roberts), who was also an artist. One can speculate on whether both these marriages fell victim to mutual competitiveness, and it seemed that Nicholson might have chosen better when he married the photographer Felicitas Vogler, with whom there was no possibility of any direct rivalry. But that marriage also ended in divorce.

I’m not sure the exhibition fully succeeds in its stated aim of exploring the impact of the personal and artistic relationships Nicholson established during his life, perhaps because ultimately a successful long-term relationship eluded him.

Nicholson himself remains an elusive figure. A non-participant in the First World War on the grounds of his asthma, he seems less shaped by social forces and wider events than many of the other greats of 20th century art. As his life unfolds, his work grows paler and whiter, reduced to line rather than volume. His pictures become almost ghosts of themselves. This exhibition does a very fine job of charting that progression.

- Ben Nicholson: From the Studio at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester until 24 October

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment