Kolesnikov, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Snape Maltings review – volcanic Britten and Vaughan Williams | reviews, news & interviews

Kolesnikov, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Snape Maltings review – volcanic Britten and Vaughan Williams

Kolesnikov, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Snape Maltings review – volcanic Britten and Vaughan Williams

Coruscating pianist and super-orchestra in abundant masterworks

They’re singing songs of praise in Aldeburgh today – namely Britten’s magical unaccompanied choral setting of Auden’s Hymn to St Cecilia on the composer’s birthday and the annual celebration of music’s martyred patron. And what a right to celebration Britten Pears Arts will have earned after a weekend of concerts from bold John Wilson’s latest super-orchestra, an army of technicolor generals.

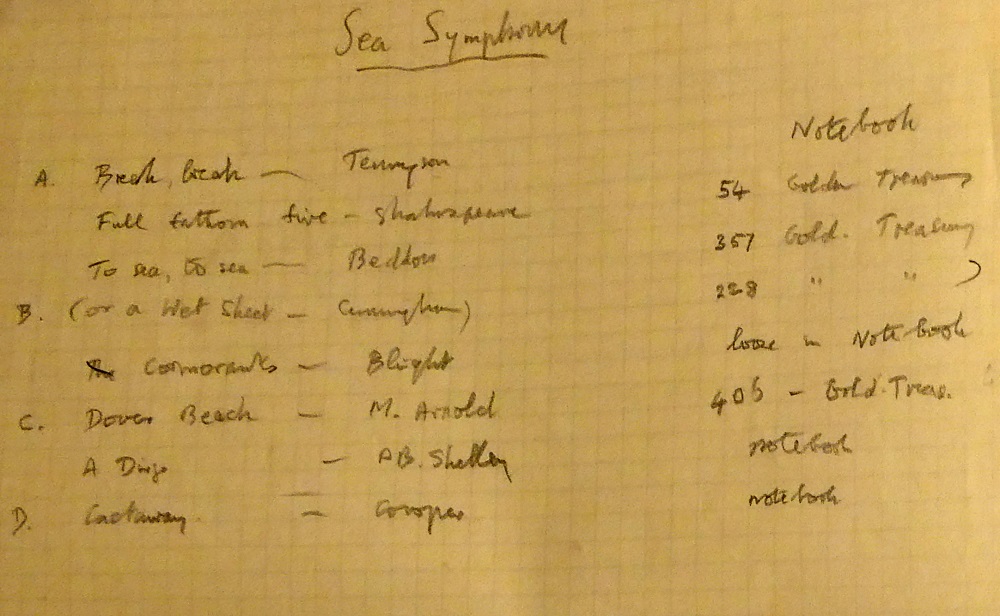

I heard the first, and possibly for me the best of 2021 (though it's not all over yet), on Saturday evening, after a return to the Red House where in 1983 we Hesse Students, jolly labour for the Aldeburgh Festival in return for concert tickets, were invited by Pears for a rather starry garden party. I’d seen the spacious library several times over the subsequent years, but not inside the house, where more top-notch paintings grace the walls, the relatively recently restored composing room or the 2013 archive building, where original letters and manuscripts pertaining to the weekend’s events were laid out for close inspection. Among them were John Ireland’s measured praise in a Royal College of Music report for the 17-year-old composition student he didn’t really understand – "industry" is underlined as the principle virtue, and "considerable grasp of technique" is highlighted – and a list of poems selected, at the end of Britten’s life, for a projected Sea Symphony (pictured below). While Vaughan Williams in his masterpiece of 1903-9 stuck to one poet, Walt Whitman, Britten was to have followed the Spring Symphony polyphony.

That was Kolesnikov’s prerogative, too, and there came a point in the opening Toccata of the Britten Piano Concerto where you felt the excitement could go through the roof, threatening to snap off. It held, and the 24-year-old composer goes further, broader and deeper than the character-titles of his movements imply – or at least it seemed so in this performance, easily the most enthralling I’ve heard of the work, So much more, then, than what it feels like in the first two movements – Prokofiev’s Sixth Piano Concerto – or the finale’s opening homage to Shostakovich’s First Symphony. Kolesnikov rode the storm, toyed with the waltz, reached out for the supernatural in the spookiest moments of the Impromptu, raised the roof in double octaves. The sense of inspiration in the moment continued with perhaps the most radical of Chopin’s Mazurkas as encore, Op 17 No 4 in A minor, its mid-air start still trailing extroversion before Kolesnikov took us into the heart of the mystery.  Kolesnikov’s praise for the orchestra seemed heartfelt, and rightly so; one unforgettable moment in the concerto was an uncanny snarl from the trombones, led by the peerless Helen Vollam. Collectively, though, the brass had most chance to shine in the romping fanfares and the ghosts of ages past of Vaughan Williams’s symphony, ringing London as an image of the world, even perhaps the universe. The hurly-burly of folksy melodies tumbled out not so much in riotous street life as in pyroclastic flows.

Kolesnikov’s praise for the orchestra seemed heartfelt, and rightly so; one unforgettable moment in the concerto was an uncanny snarl from the trombones, led by the peerless Helen Vollam. Collectively, though, the brass had most chance to shine in the romping fanfares and the ghosts of ages past of Vaughan Williams’s symphony, ringing London as an image of the world, even perhaps the universe. The hurly-burly of folksy melodies tumbled out not so much in riotous street life as in pyroclastic flows.

Here, at last, we got extended introspective poetry, rounded in miraculous solos from first viola Scott Dickinson and cor anglas player Peter Facer. VW’s divided mists of strings, too, played their part: is there anything more simple in its inspiration than the pulsing triplets on a single chord answered by two notes on the first horn in the bewitching slow movement? The finale brought an apocalypse to cap even this electrifying take on the concerto, and then the still small voice of hope that London, and all else, will endure. I bet the second concert, on Sunday afternoon, was spellbinding, too; but always best to go out on a total high.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Add comment