Blu-ray: Champion | reviews, news & interviews

Blu-ray: Champion

Blu-ray: Champion

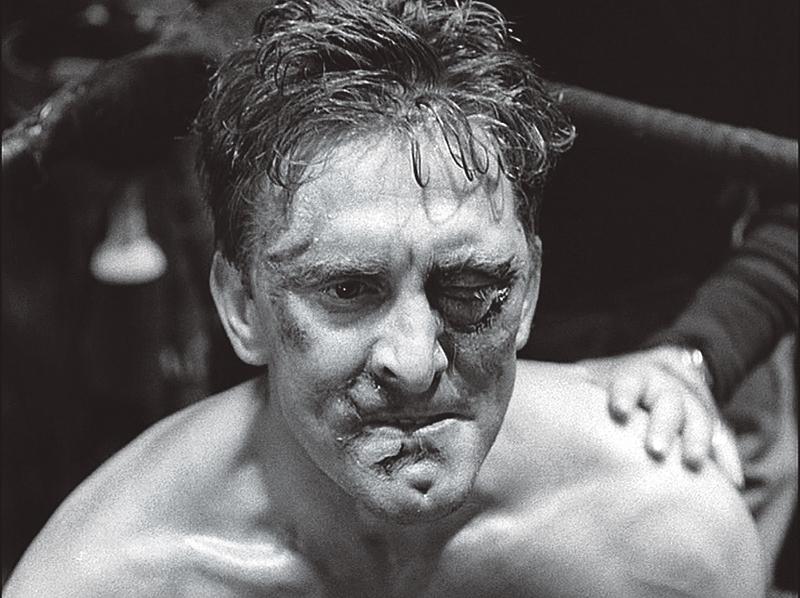

The bruising film noir that put Kirk Douglas's name in lights

Champion (1949), one of many boxing films of the 1930s and 1940s, made a sculpture – and a star – of Kirk Douglas. In one of the few non-fight scenes, Douglas, as middleweight Midge Kelly, agrees to pose for an artist (Lola Albright), but quickly gets bored.

A bruiser in and out of the ring, he’s got his eye on the artist. So he drops his robe, crushes his clay likeness, and moves in, even though she’s his manager’s wife. Midge is always on the make. What he wants, he takes. Women, trainers, managers. And he bails on them like a snake sheds its skin.

“I’m not gonna be a ‘Hey, you’ all my life,” he tells his first girlfriend (Ruth Roman), whom he dumps when she becomes an encumbrance. “I want to hear people call me Mister. I want to make something of myself.” So Champion lacks nuance. With a few notable exceptions (Body and Soul, Raging Bull, Journeyman), boxing films usually do.

In 1949, boxing’s popularity was second only to baseball. Maybe that’s why director Mark Robson seized upon this project, as did Douglas (Robson had edited Cat People and The Leopard Man for Val Lewton, but was out of work for three years before Champion.) He made up for lost time here. This movie moves fast: characters are caught in a swift current running downhill, even if they don’t know it. (Carl Foreman’s screenplay was based on a story by Ring Lardner; Lardner’s Midge is even more of a heel than in the movie.)

In 1949, boxing’s popularity was second only to baseball. Maybe that’s why director Mark Robson seized upon this project, as did Douglas (Robson had edited Cat People and The Leopard Man for Val Lewton, but was out of work for three years before Champion.) He made up for lost time here. This movie moves fast: characters are caught in a swift current running downhill, even if they don’t know it. (Carl Foreman’s screenplay was based on a story by Ring Lardner; Lardner’s Midge is even more of a heel than in the movie.)

Improbably, Champion’s hero wanders into the fight game. Thrown onto an undercard to pay a debt, Midge – whose mouth is as hard as his head – wins against an experienced athlete. Then Midge and younger brother Connie (Arthur Kennedy, excellent) hitchhike to Los Angeles, and both fall for Roman's naïve teenage waitress. But she goes for Midge, despite his red-flag confession that as a child he used to “dream of getting rich someday – rich enough to hire detectives, find my father, and then I was gonna beat his head off. You know, kid stuff.”

In one astounding shot, cinematographer Franz Planer pans from Roman and Douglas’s dangerous embrace, across a bed, to reveal her father, holding a gun on them and forcing them to marry. Midge makes a dash for the ring, for respect, for money. For a while, he gets by on pure rage.

Though Douglas sparred with real boxers and looks the part, Midge’s fight strategy is equal parts snarling, nostril-flaring, charging straight at his opponents; he’s lucky not to get killed early on. (He gets style points for shouting out his telephone number at another boxer’s girlfriend in the middle of a bout.)

Champion’s training montage does show how seriously Douglas, a former college wrestler, took his preparation for the role. According to film noir scholar Jason A Ney, it was producer Stanley Kramer, not Robson, who directed this sequence. (Ney’s thorough commentary on the Blu-ray would have worked far better if it included the option to play English subtitles for the deaf or hard of hearing at the same time.) The most Lewtonesque touch comes late in the film when Midge runs afoul of gamblers. As the racketeers stalk him and his manager beneath a cavernous city arena, Robson and Planer create a mood of sustained menace that echoes the best of Lewton's thrillers.

Champion suffers by comparison with more artistically complex fight films, but it racks up the points, and Paul Stewart gives a particularly savvy performance as Tommy Haley, Kelly’s first supporter. “You hit a man in the head hard enough and long enough, or just once, you can either scramble his brains or maybe kill him,” Haley warns Midge, neatly summing up the movie’s plot. “And for what. To fill a hall? To win bets for somebody you don’t even know? What does it prove? Is that a way to make a living?”

No other filmed sport poses the question "What is the fighting essence of a man (or woman)?" in such a small arena, and so powerfully, as boxing. And the problem with boxing is the extreme risk it involves. Joyce Carol Oates calls boxing “America’s tragic theater." Literature professor Normand Berlin suggests that we think of boxing as theatre stripped down to its essentials: actors, spectators, but no script, no text. “The agon [conflict between characters] is fascinating to watch, pure theater,” he wrote.

Yet there’s always a subtext, a shadow script. Odds are written and stacked against anyone who stays in the ring too long, as the better boxing movies – including Champion – would have it. For casualties of the sport, the shadows on their brain scans are real.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

Add comment