The Goldberg Variations, De Keersmaeker, Kolesnikov, Sadler's Wells review - keyboard harmony and atonal dance | reviews, news & interviews

The Goldberg Variations, De Keersmaeker, Kolesnikov, Sadler's Wells review - keyboard harmony and atonal dance

The Goldberg Variations, De Keersmaeker, Kolesnikov, Sadler's Wells review - keyboard harmony and atonal dance

Two major artists collaborate, leaving some unanswered questions

Jean-Guihen Queyras and five dancers of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s Rosas company in the Bach Cello Suites was a thing of constantly evolving wonder. So too is Pavel Kolesnikov’s ongoing dialogue with Bach’s Goldberg Variations, different every time he plays them. Would De Keersmaeker alone be able to hold her own dancing to this inventory of technical rigour and human emotions?

For the first, muted-silver hour, it was hard to say, given the difficulty of interpreting much in the dancer’s vocabulary and tallying it with what we were hearing in Kolesnikov’s myriad worlds. The sensation was more akin to another set of variations. Schoenberg's, where although serial rigour is applied, the feeling in performance is more one of atonal "anything goes", since given the use of 12 notes, anything can be related to anything else.  De Keersmaeker is an artist who knows how to be still and attentive, so I was expecting something along the lines of Balanchine’s choreography to Stravinsky’s Duo Concertante, where the dancers listen to violin and piano in the first movement. But the movement here is at first De Keersmaeker’s, simply continuing when Kolesnikov began the Aria, somehow the very essence of objective beauty in music.

De Keersmaeker is an artist who knows how to be still and attentive, so I was expecting something along the lines of Balanchine’s choreography to Stravinsky’s Duo Concertante, where the dancers listen to violin and piano in the first movement. But the movement here is at first De Keersmaeker’s, simply continuing when Kolesnikov began the Aria, somehow the very essence of objective beauty in music.

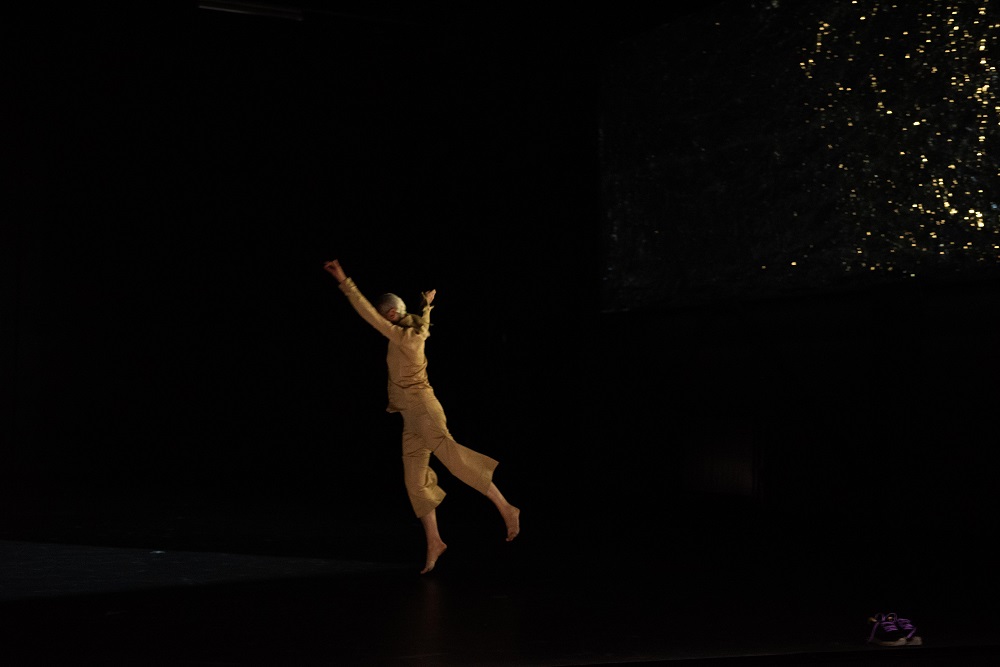

It would be simplistic to say that those movements veer between the fluid and the jerky; there’s a great deal of variety, and no repeats in the music have the same reflected dance (Kolesnikov is still at liberty to be free with them, too). Strictly no humour in the dance when there’s plenty on Bach's part, though there’s an aggressing bumping of her collaborator off the piano which gets a surprised laugh, and much later the wit is in a music-less front-of-stage interlude. Much is counter-intuitive; De Keersmaeker’s first lying-down is to the moto perpetuo of Variation 5, though others make more sense tied to the stretches where the pianist, bare-footed for this sequence, uses the sustaining pedal, and the first big minor-key variation, 15 is the one where she moves under the piano and takes hold of it in more explicit anguish.  That’s an end to the darkness, at least until the next most sorrowful stretch; after too long a break, where we’re held in our seats for about 10 minutes, De Keersmaeker emerges rejuvenated and recostumed (pictured above), like Kolesnikov, to take greater command for the next stretch; gold rather than silver now dominates. Then there’s the biggest shock of the evening, a coup that relies more on vision and the work of set and lighting designer Minna Tiikkainen than dance as Kolesnikov probes the depths of Variation 25. Fade to black, a rare sensation in the theatre; the last time I experienced it was right at the start of the Zurich Opera Wagner Rheingold, when as here even the players had no lights on the music stands. Only connect, because the big lump of gold stage left glows as the pianist miraculously holds his poise in the dark.

That’s an end to the darkness, at least until the next most sorrowful stretch; after too long a break, where we’re held in our seats for about 10 minutes, De Keersmaeker emerges rejuvenated and recostumed (pictured above), like Kolesnikov, to take greater command for the next stretch; gold rather than silver now dominates. Then there’s the biggest shock of the evening, a coup that relies more on vision and the work of set and lighting designer Minna Tiikkainen than dance as Kolesnikov probes the depths of Variation 25. Fade to black, a rare sensation in the theatre; the last time I experienced it was right at the start of the Zurich Opera Wagner Rheingold, when as here even the players had no lights on the music stands. Only connect, because the big lump of gold stage left glows as the pianist miraculously holds his poise in the dark.

For the final sequence, De Keersmaeker reappears in salmon pink top and sequinned shorts: a hint of flash in the costume, but not in the dance, which remains reserved in comparison to the music – no choreographic trumpets to the celebratory high noon of Variation 29, and what I assume to be Kolesnikov’s most radical accommodation with his dancer, a very slow, heaven-reaching fade through Variation 30 back to the Aria, De Keersmaeker finally aspiring. You don’t have to understand everything in her armoury for this singular interpretation to wonder at the integrity. Yet I did miss the joy in Bach’s music, abundant in Kolesnikov’s phenomenal playing but arguably muted to his collaborator’s needs.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment