Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, National Gallery review - a powerful punch in the gut | reviews, news & interviews

Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, National Gallery review - a powerful punch in the gut

Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, National Gallery review - a powerful punch in the gut

The complexity of human relationships laid bare in centenary show of the artist who always disturbs

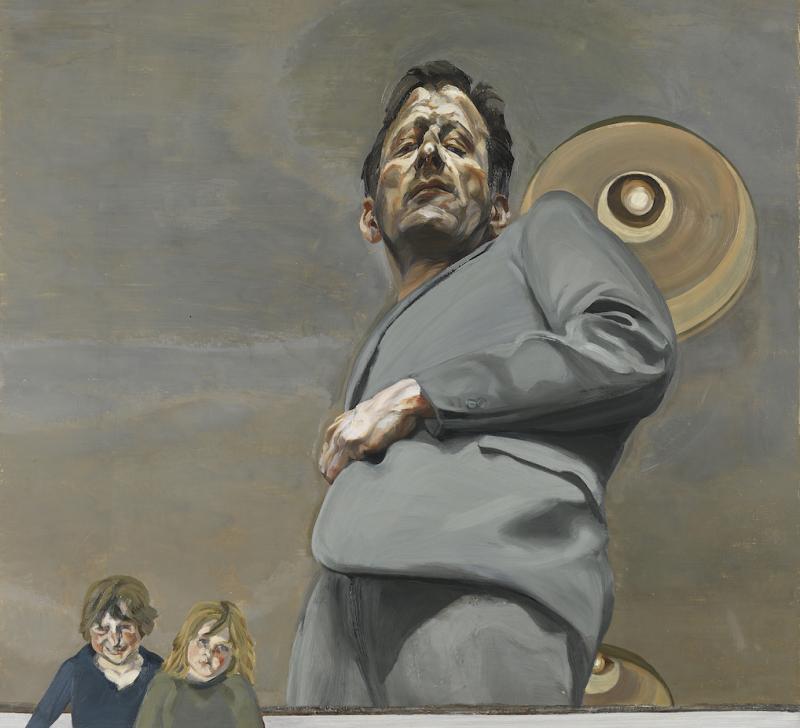

There stands Lucian Freud in Reflection with Two Children (Self-portrait), 1965 (main picture) towering over you, peering mercilessly down. Is that a look of scorn on his face or merely one of detachment? His two kids seem to be squirming and giggling beneath their father’s unblinking stare. Who wouldn’t be, especially when the huge lamps hanging overhead are reminiscent of an interrogation chamber? All the better to see you with, my dear.

Portraits, or rather paintings of people, were Lucian Freud’s speciality. He spent 70 years relentlessly scrutinising his own and his sitter’s faces and bodies and recording what he saw in paintings whose visceral power is like a punch in the gut.

Celebrating the centenary of Freud’s birth, the National Gallery’s retrospective confirms him to be a colossus of 20th century art. The artist had a close association with the gallery and one purpose of this exhibition is to show his work in the context of the great portraits of the past, to which he often looked for inspiration and ideas.

Celebrating the centenary of Freud’s birth, the National Gallery’s retrospective confirms him to be a colossus of 20th century art. The artist had a close association with the gallery and one purpose of this exhibition is to show his work in the context of the great portraits of the past, to which he often looked for inspiration and ideas.

But there’s a significant difference between his relationship with his sitters and that of old masters like Titian, Holbein or Van Dyck. Freud’s approach is without deference; he never attempts to flatter or aggrandise. The clearest example is his portrait of the late Queen from 2001. Not only is the monarch tiny, but Freud is looking down at her; and despite having a crown perched on her head, there is nothing majestic about her image. On the contrary, she looks slightly ridiculous. For all the dignity he bestows on her, this queen could be a turnip or a cabbage!

Nearly all his encounters in the studio seem full of tension; there’s a power struggle going on. Beneath his gaze, his sitters appear uniquely vulnerable – stripped bare often both literally and metaphorically. In Double Portrait 1986 (pictured above right), the sitter covers her eyes and tries to sleep, as though to shield herself from prying eyes. Even though she is dressed, staring at her still feels like an act of trespass, a gross intrusion of privacy. Gazing at the dog lying beside her, on the other hand, creates no such embarrassment; the animal displays no discomfort at being observed. Perhaps lacking the self-awareness that can plague us, he is completely at ease.

Nearly all his encounters in the studio seem full of tension; there’s a power struggle going on. Beneath his gaze, his sitters appear uniquely vulnerable – stripped bare often both literally and metaphorically. In Double Portrait 1986 (pictured above right), the sitter covers her eyes and tries to sleep, as though to shield herself from prying eyes. Even though she is dressed, staring at her still feels like an act of trespass, a gross intrusion of privacy. Gazing at the dog lying beside her, on the other hand, creates no such embarrassment; the animal displays no discomfort at being observed. Perhaps lacking the self-awareness that can plague us, he is completely at ease.

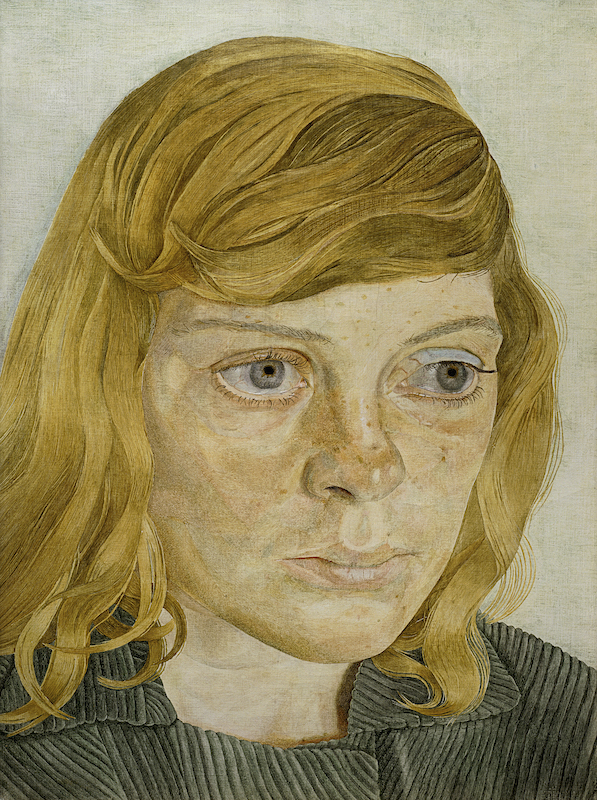

Freud’s early paintings are exquisite in their limpid clarity; built up in translucent layers through which the eye can penetrate, they make you feel as if you can get under the sitter’s skin. A tender portrait of his new wife, the author Lady Caroline Blackwood, Girl in a Green Dress, 1954 (pictured above left) creates a mood of nervous introspection. We are too close for comfort and, while Caroline’s right eye looks steadily ahead, the other glances sideways as if seeking some means of escape.

Painted in chilly shades of grey, his portrait of the artist John Minton, 1952 suggests extreme unease. The tilt of the head, the bony angularity of the features and the anxiety in his eyes suggest that the sitter is almost suicidal.

Freud was born in Berlin in 1922, grandson to the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. The family fled the Nazis and came to Britain in 1933. Freud vehemently rejected the idea of having any links with Germany, but these early paintings share the almost surreal intensity of work by Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) artists like Christian Schaad and Otto Dix and their encapsulation of collective fear and disquiet.

In 1954 Freud began painting standing up and gradually changed his technique. In place of delicate washes of subtle colour, he began lathering on the paint, often building up the surface until it becomes encrusted with dabs of oil. Close to, the canvases are clogged and inert, but stand back and, miraculously, they cohere into three-dimensional depictions.

In 1954 Freud began painting standing up and gradually changed his technique. In place of delicate washes of subtle colour, he began lathering on the paint, often building up the surface until it becomes encrusted with dabs of oil. Close to, the canvases are clogged and inert, but stand back and, miraculously, they cohere into three-dimensional depictions.

I’ve always disliked the opacity of these clotted surfaces, which can make his sitter’s flesh look scabby and leprous; but one of the joys of seeing the paintings in such large rooms is that you have the space to realise how powerful they are from a distance.

There’s nothing comfortable about any of these encounters, though. It’s as if Freud wants you to question who has the right to look at whom. Who is in control and how much does looking tell you, anyway? In Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, 1996 (pictured above right) he contrasts the mountainous flesh of the slumbering Sue Tilley with the agile bodies of hunting lions, woven into the rug behind her. Even though she must have given consent, the juxtaposition feels insulting and exploitative – a deliberate provocation.

And he likes to complicate the relationship between artist and sitter in unexpected ways. As though to make things seem unstable, in Two Men, 1988 he tilts up the picture plane to the point where the couple on the bed look as if they are sliding down a lift shaft. Look again at Reflection with Two Children (Self-portrait) (main picture) and you realise the kids are not standing beside the artist but are in front of a large self-portrait; the artist is not staring at us, but peering down at his own reflection. He is both in the picture and outside it at the same time.

Reflections crop up repeatedly; Freud is often to be seen painting himself in a mirror. Reflection also means taking stock, of course, and Freud uses the word to equate painting with introspection – with assessing the self. And when he strips naked to portray his scrawny, 71-year-old body (pictured left) with the same dispassion as he views everyone else, one can forgive his eagle-eyed analysis. Far from being an act of humility, though, the painting is a vanitas in that it refers to Michelangelo’s depiction of St Bartholomew on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The saint was flayed alive and, in one hand, he holds the offending knife (Freud brandishes a palette knife) and, in the other, his flayed skin onto which Michelangelo has painted a self-portrait. Freud is comparing himself, unashamedly, with the Renaissance master.

Reflections crop up repeatedly; Freud is often to be seen painting himself in a mirror. Reflection also means taking stock, of course, and Freud uses the word to equate painting with introspection – with assessing the self. And when he strips naked to portray his scrawny, 71-year-old body (pictured left) with the same dispassion as he views everyone else, one can forgive his eagle-eyed analysis. Far from being an act of humility, though, the painting is a vanitas in that it refers to Michelangelo’s depiction of St Bartholomew on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. The saint was flayed alive and, in one hand, he holds the offending knife (Freud brandishes a palette knife) and, in the other, his flayed skin onto which Michelangelo has painted a self-portrait. Freud is comparing himself, unashamedly, with the Renaissance master.

When he curated an Artist’s Eye exhibition at the National Gallery in 1987, he wrote: "What do I ask of a painting? I ask it to astonish, disturb, seduce, convince." No matter what you think of his chutzpah, you have to agree that he achieved all of those objectives. I always long for an exhibition that will open my eyes to something I’d not understood or not known before. And this is it. Seeing so much of his work together, reveals Freud as a far more complex and interesting artist than I had suspected. And since it forms part of a quest to interrogate the complexity of human relationships, I can forgive the arrogance of his vision and marvel at the brutal power of his pictures.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment