Light of Passage, Royal Ballet review - a new full-evening work by Crystal Pite is eloquent and moving | reviews, news & interviews

Light of Passage, Royal Ballet review - a new full-evening work by Crystal Pite is eloquent and moving

Light of Passage, Royal Ballet review - a new full-evening work by Crystal Pite is eloquent and moving

Proof, once again, that ballet has the muscle to tackle big topics

Marshalling a mass of bodies around a stage is what all choreographers do. But nobody does it quite like Crystal Pite, the Canadian whose half-hour piece "Flight Pattern" – a comment on the global refugee crisis – was a hit for the Royal Ballet five years ago, earning an Olivier Award.

She now returns with a full-evening extension of that material, adding two new sections that address equally big subjects, not least the rights of children to life and safety. This, along with a final section dealing with what Pite calls “the ultimate border crossing”, makes sense of the work’s over-arching title, Light of Passage, though its suggestion of a verbal pun is, I feel, slightly misplaced. This is serious, thought-provoking work that dares you to suppose that ballet could ever be anything less than serious. Yet it also delivers eyefuls of glorious synchronised movement that leave you simultaneously wrung out and uplifted.

Henryk Górecki’s three-part Symphony of Sorrowful Songs supplies the emotional canvas. Written in 1977 for large orchestra and solo soprano, it sets three texts on the theme of death, addressed either from mother to child, or from child to mother. The short middle movement – a sombre lullaby that rocks softly and mesmerically between repeated chords – became the stuff of recording legend in the early Nineties when, as a result of being played incessantly on Classic FM, it reached No.6 on the UK album chart, briefly outselling Paul McCartney and REM. There’s surely a marketing opportunity here for the Royal Opera House. A ticket deal with commercial radio could be just what’s needed to broaden its audience.

My guess is that the dancers love being a part of Pite’s meticulously wrought patterns as much as we take satisfaction in watching them. The most potent motifs are the simplest, magnified large – 36 heads in tight serried rows dipping and turning just so, 36 bodies swaying or stooping in tight unison, suggesting trudging lines of dispossessed people. When Flight Pattern premiered in 2017, it seemed to be about the asylum seekers who were gathering in knots of misery on many of the coasts of Europe. In 2022 it summons thoughts of Ukrainians fleeing their homes. Pite’s genius is not only in making images that are universal, but in making tragic images devoid of mawkishness. Only once does the piece focus on the plight of a couple, picked out from the faceless crowd. Kristen McNally (pictured above) keens over the dead baby – a crumpled coat – in her arms, while Marcelino Sambé kicks off into paroxysms of airborne rage at the injustice of it. Later, Pite shows how a single image can be made to work overtime as McNally becomes the receiver of so many dumped coats that she collapses under the weight of them. Now we not only think of the deaths of children, but also of the clothing collections at Nazi workcamps. The greatest art is rarely tethered to a time or place.

My guess is that the dancers love being a part of Pite’s meticulously wrought patterns as much as we take satisfaction in watching them. The most potent motifs are the simplest, magnified large – 36 heads in tight serried rows dipping and turning just so, 36 bodies swaying or stooping in tight unison, suggesting trudging lines of dispossessed people. When Flight Pattern premiered in 2017, it seemed to be about the asylum seekers who were gathering in knots of misery on many of the coasts of Europe. In 2022 it summons thoughts of Ukrainians fleeing their homes. Pite’s genius is not only in making images that are universal, but in making tragic images devoid of mawkishness. Only once does the piece focus on the plight of a couple, picked out from the faceless crowd. Kristen McNally (pictured above) keens over the dead baby – a crumpled coat – in her arms, while Marcelino Sambé kicks off into paroxysms of airborne rage at the injustice of it. Later, Pite shows how a single image can be made to work overtime as McNally becomes the receiver of so many dumped coats that she collapses under the weight of them. Now we not only think of the deaths of children, but also of the clothing collections at Nazi workcamps. The greatest art is rarely tethered to a time or place.

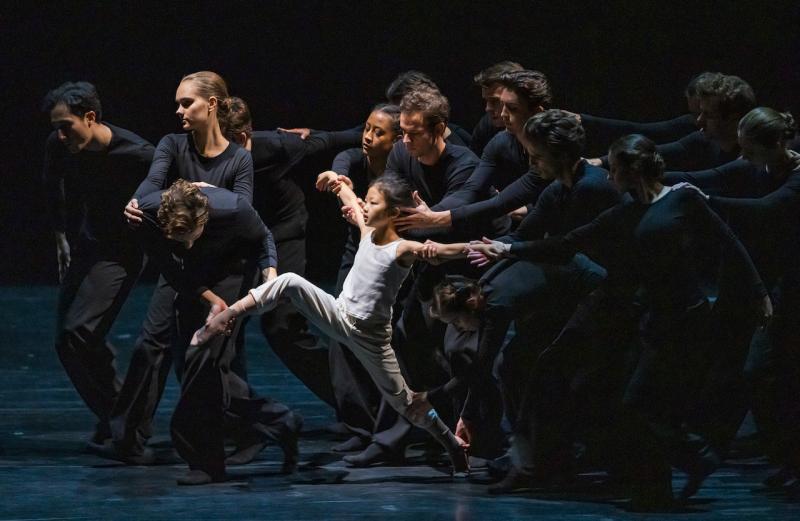

Pite brightens the tone for the second movement, Covenant. Her source for the choreography is striking: the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, in a version written for children to read. Article 31,“You have a right to play”, is an obvious one to dance, but Article 7, “You have the right to have a name” is more challenging. Pite’s introduction to the stage of six dancing children – angelically clad in white, to be guided and enabled (pictured top) by the black-clad corps – is inspired. Of many lovely moments, the most touching is when the adults form long corridors along which each child can run – unmolested, confident and free.

The 20-minute final section, Passage, imagines the end of life, introducing two seniors from Sadler’s Wells’ Company of Elders to enact some tender scenes of leave-taking. The full corps, now in ivory trouser suits (pictured above), flow around them, couples now and again breaking out into intimate duets. A same-sex duo, Luca Acris and Benjamin Ella, remind us that dying doesn’t only happen to the old. But the crowning glory is a long balletic segment in which, as the music’s ostinato plods towards its quiet climax, the 36 dancers move in waves of perfect unison, silkily turning and scooping the air as if stirring double cream. Too bad the ecstasy gives out a few minutes short of the ending, but there’s too much to love about this work to quibble.

The 20-minute final section, Passage, imagines the end of life, introducing two seniors from Sadler’s Wells’ Company of Elders to enact some tender scenes of leave-taking. The full corps, now in ivory trouser suits (pictured above), flow around them, couples now and again breaking out into intimate duets. A same-sex duo, Luca Acris and Benjamin Ella, remind us that dying doesn’t only happen to the old. But the crowning glory is a long balletic segment in which, as the music’s ostinato plods towards its quiet climax, the 36 dancers move in waves of perfect unison, silkily turning and scooping the air as if stirring double cream. Too bad the ecstasy gives out a few minutes short of the ending, but there’s too much to love about this work to quibble.

Górecki’s music is given admirable restraint by the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House under conductor Zoi Tsokanou – a fitting choice, being the first woman to head up a major orchestra in her native Greece, a country which has had more than its share of migrant grief. As the solo soprano, Francesca Cheijina finds just the right note of instrumental plangency, sounding for all the world like part of the orchestra.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment