Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - lightning speed brushwork by an Impressionist maestro | reviews, news & interviews

Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - lightning speed brushwork by an Impressionist maestro

Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - lightning speed brushwork by an Impressionist maestro

An Impressionist painter's view from inside the boudoir

When Berthe Morisot organised the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, along with Monet, Degas, Renoir and co, she’d already exhibited at the Paris Salon for a decade – since she was 23. That’s not bad for someone refused entry to art school because she was a woman!

Luckily, Berthe and her sister Edma had parents wealthy enough to employ artists like the renowned landscape painter Camille Corot to give them private lessons. They even had their own studio and, judging by the landscape included in the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s (DPG) show, Edma was rather good; but as was expected of an upper class woman, she stopped painting when she got married.

Luckily for us, Berthe persisted even after marrying Edouard Manet’s brother, Eugene, and she became spectacularly good. Corot encouraged her to work en plein air, but for a woman to paint outdoors was considered scandalous; so to avoid prying eyes, she went out at the crack of dawn. Perhaps because she had to work as fast as possible, her watercolours of fields, rivers and woodlands are executed in speedy dabs, dots and flickers of watercolour that convey the scene with incredible vitality. This is Impressionism at its very, atmospheric best. But the DPG exhibition doesn’t include any of these marvels; instead it concentrates on Morisot’s admiration for 18th century artists like Boucher, Fragonard and Watteau, whose paintings she copied in the Louvre, and English equivalents such as Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds whose work she saw on her honeymoon here. Critics often compared her lightness of touch and feathery brush marks with Fragonard’s. Paul Girard, for instance, referred to her work as “the 18th century modernised” and Renoir described her as “the last elegant and feminine artist since Fragonard”.

But the DPG exhibition doesn’t include any of these marvels; instead it concentrates on Morisot’s admiration for 18th century artists like Boucher, Fragonard and Watteau, whose paintings she copied in the Louvre, and English equivalents such as Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds whose work she saw on her honeymoon here. Critics often compared her lightness of touch and feathery brush marks with Fragonard’s. Paul Girard, for instance, referred to her work as “the 18th century modernised” and Renoir described her as “the last elegant and feminine artist since Fragonard”.

The curators have mainly selected portraits and domestic scenes that support the idea of her as a throwback and have hung them alongside 18th century counterparts. So Morisot’s Winter (1880) of a woman in a fur muff and hat hangs beside George Romney’s 1781 painting of the actress Mrs Mary Robinson in similar attire. Boucher’s Young Woman Sleeping is hung near Morisot’s Resting (1892) (pictured above), as though his brainless cuties had influenced her quietly introspective women. If I were to compare the gentle intimacy of Morisot’s oddly beautiful painting with the work of another artist it would be Edouard Vuillard, who was 27 years her junior.

Rather than confirming her place in art history, these juxtapositions give the impression that Morisot’s work can’t stand alone, but needs to be bolstered by the addition of male forerunners. Given that she was unbelievably prolific – she produced some 860 paintings before her untimely death at the age of 56 – this implication is frankly preposterous.

Thinking of her as the reincarnation of male antecedents might have made her prodigious talent less threatening to her contemporaries; now the time has come, though, to look at her work in the context of its own time and to appreciate just how radical was her vision.

Thinking of her as the reincarnation of male antecedents might have made her prodigious talent less threatening to her contemporaries; now the time has come, though, to look at her work in the context of its own time and to appreciate just how radical was her vision.

Given the social constraints imposed on her, not surprisingly, she worked mainly indoors, painting family and friends as well as professional models. Apart from her husband, all her sitters were women and children. She often posed for Edouard Manet but, tellingly, he didn’t return the favour. She didn’t have a studio – which could have been too strong a declaration of ambition – but painted in the living room and bedroom.

Imagine the inconvenience of the arrangement, of having to clear up all the time; if you’ve ever tried painting in oils you’ll know what a smelly, slow and messy business it is. But she persevered and developed the ability to work fast. To speed up the process, she made innumerable preparatory drawings and sketches before beginning an actual painting. She also developed lightning speed brush work with which she conjured light, atmosphere and movement as well as the human presence.

The whole surface of Woman at Her Toilette, 1880 (main picture) is alive with silvery grey flicks of the brush that indicate a mirror, floral wallpaper, toiletries and a delicate gown flecked with white highlights. At the centre of this visual maelstrom sits a woman; the curve that sweeps one’s eye from her shoulder and across her back to the arm reaching up to untie her hair seems scarcely to be drawn, yet it articulates the three-dimensional space of the room. Details like the woman’s shiny earring and black velvet ribbon anchor the composition and provide a resting place for the eye. This stunning painting is a masterclass in how to transcribe a transitory moment onto canvas and make it look effortless.

Morisot invites us into the private domain of women, a realm which intrigued Degas and Toulouse Lautrec as well as Fragonard and Boucher; but there’s no hint of the voyeurism or naughty knickers titillation indulged in by the men. Morisot’s women occupy a different universe from Boucher’s sexy playmates. Rather than flirtatious little kittens, they are individuals with rich inner worlds, and they are minding their own business – reading, painting, playing the piano, watering plants, chatting, getting dressed or getting ready for bed. If they acknowledge the viewer at all, it’s with calm indifference rather than seductive glances.

Morisot invites us into the private domain of women, a realm which intrigued Degas and Toulouse Lautrec as well as Fragonard and Boucher; but there’s no hint of the voyeurism or naughty knickers titillation indulged in by the men. Morisot’s women occupy a different universe from Boucher’s sexy playmates. Rather than flirtatious little kittens, they are individuals with rich inner worlds, and they are minding their own business – reading, painting, playing the piano, watering plants, chatting, getting dressed or getting ready for bed. If they acknowledge the viewer at all, it’s with calm indifference rather than seductive glances.

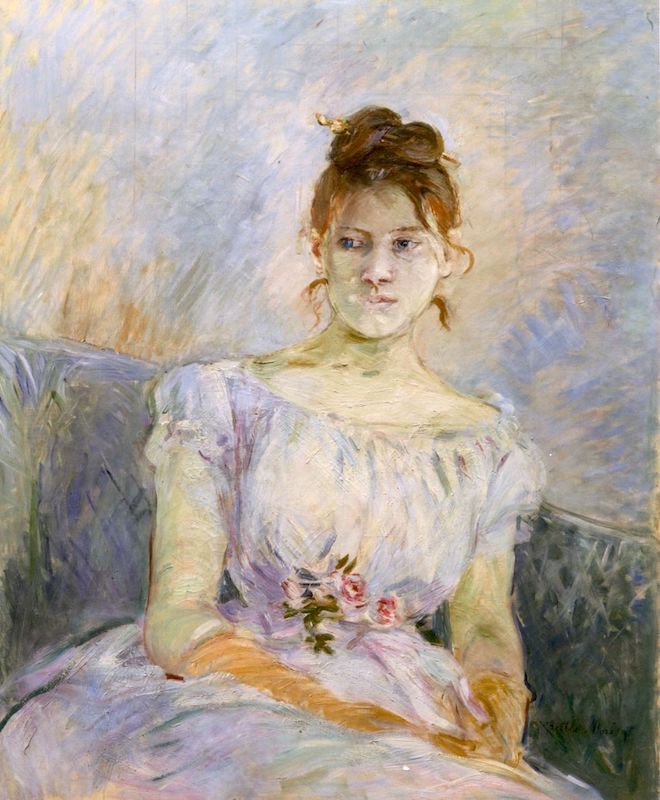

Take her 1887 portrait of Paule Gobillard, for instance (pictured above right). The young woman may be wearing a ballgown, but she looks decidedly disenchanted by the prospect of yet another party. All attention is focused on her head and, by implication, the thoughts pulsing through her brain. This reluctant débutante was Morisot’s niece and another picture shows her busily painting. Morisot taught and encouraged her niece and I can’t help seeing this portrait as the depiction of an upper-class girl trapped within a social milieu that severely restricts her options.

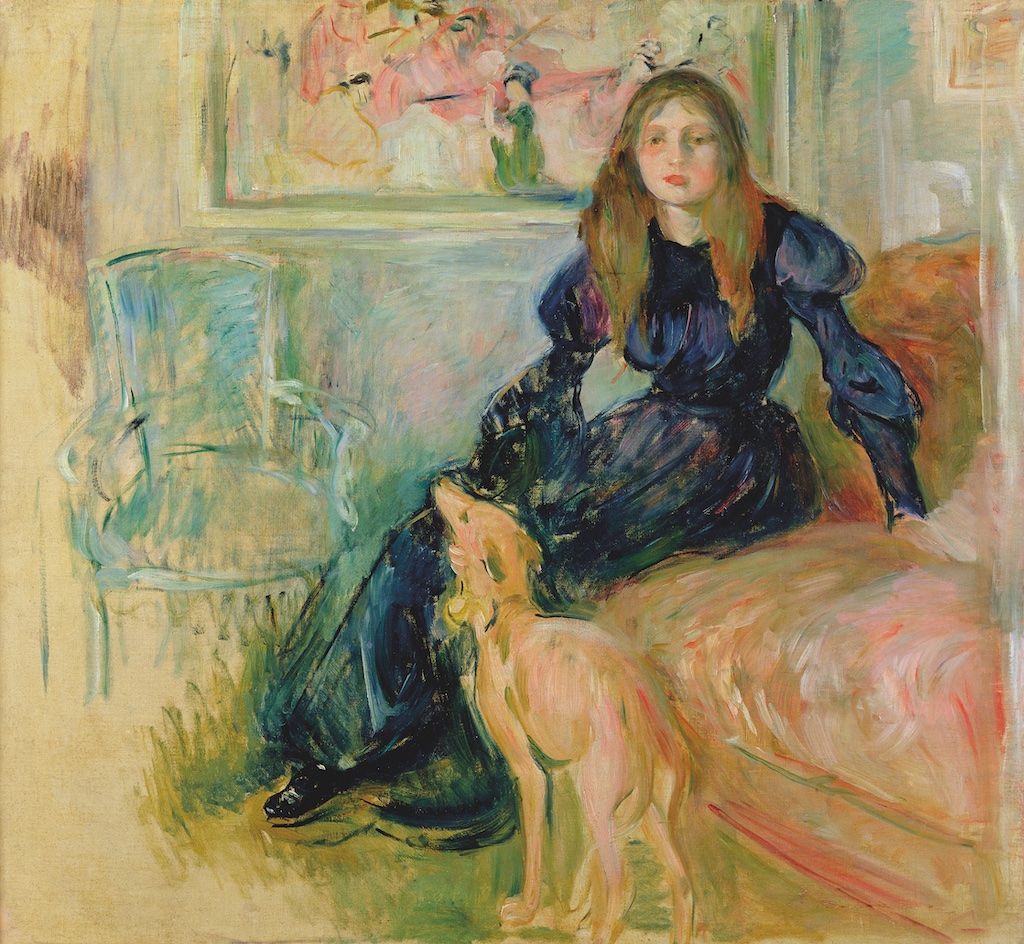

In Children with a Basin, 1886 the wizardry of Morisot’s rapid fire brushstrokes really comes to the fore. She uses them to capture the energy and excitement of her young daughter, Julie as she plays at catching goldfish with a playmate. Julie often posed for her mother; seven years later we see her wearing black in mourning for her father (pictured below). She sits alone on a sofa, staring blankly into space, comforting herself by stroking her pet greyhound. Her surroundings dissolve into abstraction as though, with her father’s death, her world has been emptied of meaning. The picture feels like a new direction. The paint has become more liquid and Morisot’s feathery brush strokes have begun to lengthen. With its melancholy mood and fluid paintwork, one could easily mistake it for a painting by Norwegian artist Edouard Munch (of The Scream).

The picture feels like a new direction. The paint has become more liquid and Morisot’s feathery brush strokes have begun to lengthen. With its melancholy mood and fluid paintwork, one could easily mistake it for a painting by Norwegian artist Edouard Munch (of The Scream).

In a self-portrait painted at the age of 44 (pictured above left), Morisot appears confident, determined and professional – an independent spirit well able to endure widowhood; but it was not to be. She died of pneumonia only two years after her husband’s death, and we will never know how her work would have progressed.

It’s 70 years since Berthe Morisot was last shown in this country, so it’s unsurprising that her achievements are not well known here. While the Dulwich Picture Gallery exhibition does her no favours, it has made me eager to see a full retrospective. Given that in 2013 her painting Apres le Déjeuner 1881 fetched £6.2 m – then, the highest price for a female artist – I'd say she deserves one.

- Berthe Morisot at the Dulwich Picture Gallery until 10th September

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment