From the moment that the blood-stained Nathuram Godse rises out of the floor of the National Theatre's Olivier stage and demands ‘What are you staring at? Have you never seen a murderer up close before?’, we are locked into a queasy, teasing relationship with the man who killed Mohandas Gandhi, the latter renowned throughout the world for his passive but effective resistance to British colonial rule in India.

Returning for a second run, Indhu Rubasingham’s production has several new cast members, including Hiran Abeysekera as Godse. Playwright Anupama Chandrasekhar was the National’s first international writer-in-residence and her surprisingly humorous play is very much written with a British audience in mind. In her examination of the assassin rather than the father, she asks how did the former become an extremist, and how did he come to believe that killing Gandhi would be an admirable thing to do.

Abeysekera, who won an Olivier award for his performance in The Life of Pi, relishes his new part. Brash, troubled, and coquettish, Godse is challenging from the start, confident that our knowledge of Gandhi’s life is pretty much based on ‘that fawning Attenborough film’. In truth, given how long ago that film was made, maybe even less is known now. A small, energetic figure, Abeysekera defiantly narrates the facts of Godse’s life, occasionally charming us with his wit, while his eyes betray his unease. In an outstanding performance of great clarity and commitment, he portrays a man who is never comfortable in his own skin. His relationship with the audience lifts what could be a conventional, biographical drama into something far more interesting. How can we be sure that he is telling the truth? Much to his annoyance, Aysha Kala’s Vimala, a childhood friend and follower of Gandhi, occasionally interrupts to set the record straight.

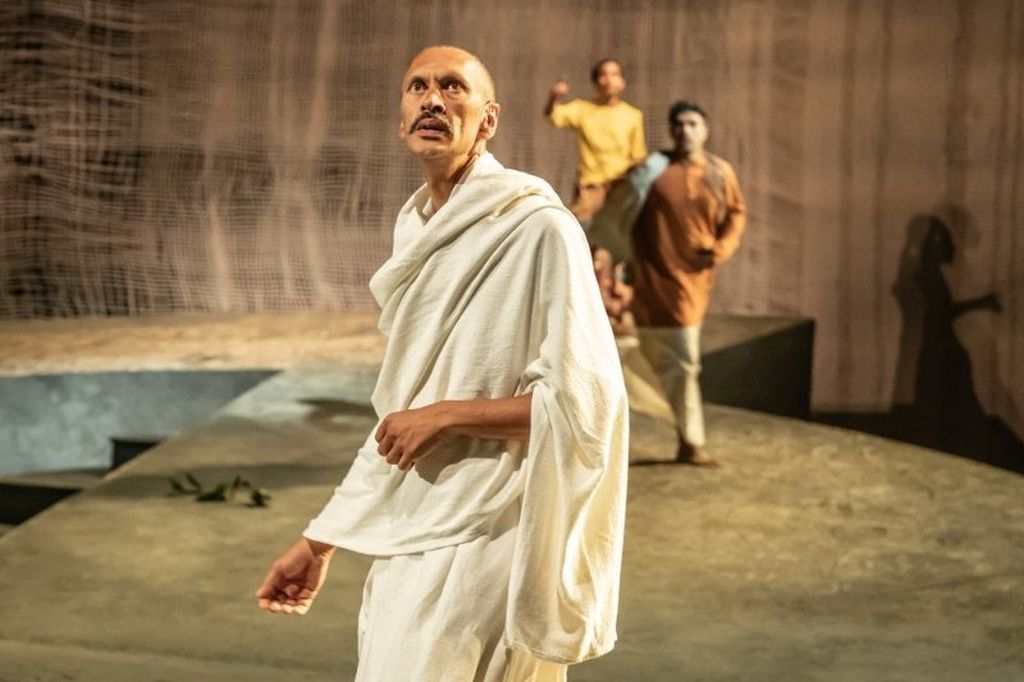

The modern resonances abound without ever being spelt outUnlike Gandhi, little is known about Godse, and so Chandrasekhar has a certain amount of wiggle room, but the bizarre childhood she describes is, by all accounts, true. Having lost three sons, his parents decided that the male line was cursed and so brought Godse up as a girl known as Nathu or Nose-ring. Skipping around the stage, Godse also reveals that as a child - and here we are asked to put our scepticism aside - the Goddess Durga blessed him with the power of prophecy and his parents’ income was augmented by a stream of people coming to discover their futures. The power left him when, as Chandrasekhar imagines it, Godse encountered Gandhi (Paul Bazely, pictured below) who guessed the truth and kindly encouraged him to shed his skirts. No wonder, the leader becomes the first of Godse’s several father figures.

Later, Godse rejects Gandhi and pacifism and comes under the influence of the powerful figure of the Hindu Nationalist and Nazi sympathiser, Vinayak Savarkar, who believes that Muslims are as much the enemy as the British. ‘The only key to nation building is homogeneity,’ he claims. The play covers tumultuous events and occasionally the politics feel over-simplified, especially the debates between Gandhi, Jinnah and Nehru as Gandhi desperately clings to the idea of Hindus and Muslims living in harmony in one country. While an effort to portray the horrific events of the Partition feels clumsy, Gandhi’s march against the salt tax is portrayed with great simplicity and power.

Later, Godse rejects Gandhi and pacifism and comes under the influence of the powerful figure of the Hindu Nationalist and Nazi sympathiser, Vinayak Savarkar, who believes that Muslims are as much the enemy as the British. ‘The only key to nation building is homogeneity,’ he claims. The play covers tumultuous events and occasionally the politics feel over-simplified, especially the debates between Gandhi, Jinnah and Nehru as Gandhi desperately clings to the idea of Hindus and Muslims living in harmony in one country. While an effort to portray the horrific events of the Partition feels clumsy, Gandhi’s march against the salt tax is portrayed with great simplicity and power.

Rubasingham’s sweeping production makes full use of the revolving stage. The impressive design by Rajha Shakiry is dominated by a vast, half-woven cloth, recalling Gandhi’s obsession with weaving. Neutral colours prevail with the occasional splash of saffron and crimson. A sense of India is created without any of the usual clichés.

Although this is a history play, the modern resonances abound without ever being spelt out (except for a left-field reference to Brexit). As Prime Minister Modi’s India embraces Hindu Nationalism today, Godse’s reputation has risen and there have even been calls for a statue to be erected in his honour. Maybe a man who was a loner, who would surely be venting his fury on social media if he were alive today, is finally getting the recognition he craved. Chandrasekhar treads a delicate line as she and Abeysekera manage to maintain our interest in Godse without, hopefully, ever sharing his enthusiasm for racial violence. That tightrope is particularly acute in his final speech which is an angry call to strike your enemies down. As the play ends, one is torn between cheering the performance and booing the words.

Add comment