I turn 36 this year, while living in London and rehearsing my new play The Fear of 13 at the Donmar Warehouse. The cast places a cake on my desk, covered in script pages and 10 pairs of handcuffs. I video the cake, the handcuffs, the singing actors – led by Adrien Brody – who have now broken into a sort of birthday rap. I text the video 5,500 miles to LA to my friend Nick Yarris, the man about whom I wrote the play, whom Adrien Brody is playing.

Nick always responds immediately: “I love how you use my time on death row as a merriment,” he ribs, noting the delicious looking dessert sitting atop prop restraints, asking to save some for him for when he gets to London for opening.

I send him back a laughing emoji. “Making a play is so weird,” I say.

“No. Living a life that someone makes a play about is what’s weird,” Nick replies.

*******

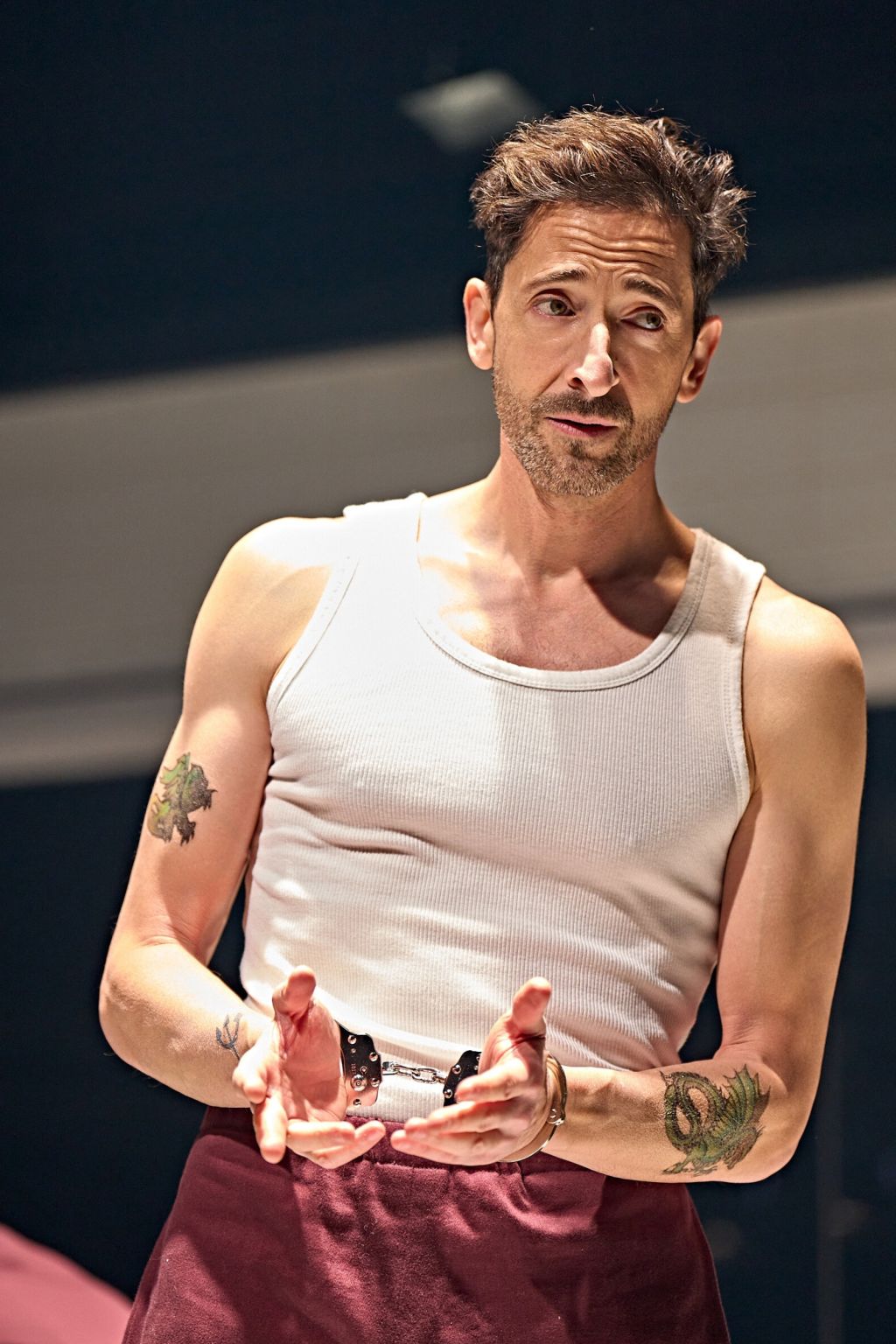

Adrien Brody asks me if Nick got any tattoos in prison, and so I ask Nick who sends back three photos with accompanying stories. I email them to stage management, who sends them to the make-up designer, who starts figuring out a way to replicate them on Adrien Brody’s arms. (Lindsey Ferrentino pictured right, c. Kathryn Page)

Adrien Brody asks me if Nick got any tattoos in prison, and so I ask Nick who sends back three photos with accompanying stories. I email them to stage management, who sends them to the make-up designer, who starts figuring out a way to replicate them on Adrien Brody’s arms. (Lindsey Ferrentino pictured right, c. Kathryn Page)

Nick sends me instructions on how to create a prison tattoo gun out of an electric toothbrush. It’s irrelevant to the show, but he thought it would make me laugh, and he feels it’s important for my education.

*****

The Donmar has hired Nick as a consultant to his own life story and I, having developed a friendship with Nick over the course of writing the play, am the point-person for communication.

Though Nick and I normally talk on a daily basis, when we start rehearsals I am suddenly selfconscious about asking specific production-related questions, sensitive to the fact that they are often about his trauma. I ask if he has any boundaries around what I can ask. He says no, and that if I don’t ask prying questions he will be disappointed, insisting I text him as they come up in rehearsal; that he’d rather be involved in the process.

And so I do. And the facts roll in. The details that enrich the story.

Nick wore handcuffs at all times, except for when he was locked in his visiting booth. The guards would beat anyone who spoke. His prison uniform was a deep maroon, but bright orange when they arranged transport. He once played Patty Cake with a cannibal.

I become the middleman between the pretend world of the play, and the real world the play is based on; the pit stop between reality and recreation. This is a literalisation of how I see my role as a playwright when writing true stories. Every moment in the show is a delicate balancing act of wanting to honour the truth of what actually happened, but present it in a way that is digestible for an audience. (Adrien Brody, pictured left)

I become the middleman between the pretend world of the play, and the real world the play is based on; the pit stop between reality and recreation. This is a literalisation of how I see my role as a playwright when writing true stories. Every moment in the show is a delicate balancing act of wanting to honour the truth of what actually happened, but present it in a way that is digestible for an audience. (Adrien Brody, pictured left)

The issue of onstage violence comes up often. Nick wants to make sure that we don’t soften the world too much. How do you make it clear for an audience the repressive, authoritarian environment that Nick lived in for 22 years without making an audience feel assaulted themselves, and therefore unable to engage with the story?

I am also hyper-aware of the complicated ethics of creating drama for an audience out of someone’s lived-in, personal trauma. Nick and I discuss this at length: how the play, to him, will feel like part-celebration and part-eulogy. I ask him what he thinks it will be like to see the hardest moments of his life played out in front of an audience…

********

We do our first run-through of the play and I text about how excited I am for him to finally see the show.

Nick responds: “Look at the gift you and I get today. The best actor in the world is taking your art and supercharging it. Then there’s me… My pain is being erased by Adrien. The man is lifting my woes and making all the shit they did to me worth it. No one will get this, but you and Adrien… you’re taking the beatings back… My broken face can smile without shame.”

*******

There is a discussion in the room about whether or not people on death row were given any special privileges on Christmas day. I text Nick and ask. “I like how you keep trying to make me laugh with that image that there was a party going on at Christmas on death row,” he says.

He explains how, for a few years, Christian groups brought in small Ziploc bags of cookies, packaged with a trinket like a small piece of origami; how a preacher, accompanied by a heavily armed guard, would distribute the bags, asking each man if he would like to participate in the birth of Christ; how Nick chose to just accept the cookies and keep quiet.

I explain that we are debating if this scene should be underscored with Christmas music. Nick says there would be no music. Only silence.

But Nick generously adds, “It doesn’t matter about the reality if you have an idea that works. Just please do something beautiful.

Add comment