You may have heard the phrase “elevated horror” being used to describe horror films that lean more toward arthouse cinema, favouring tension and psychological turmoil over jump-scares and gore.

It was first used to describe a crop of horror films released in 2014, including Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook, David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows, and Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walk Home Alone at Night, but it has also been used to describe some of the most recognisable horror films of the decade by directors like Robert Eggers, Jordan Peele, and Ari Aster.

To some this is an innocent enough descriptor. To others, "elevated horror" causes a visceral reaction. They deem it a backhanded compliment that reeks of the same snobbery that banished horror from the house of respectable film discourse. In her new book Feeding the Monster (Faber), the critic and author Anna Bogutskaya reveals she belongs to the latter group. “It is a phrase that generates an unusual amount of bile in me”, she writes. In her taut overview of the past 10 years of horror cinema, Bogutskaya argues that, as with any genre, there are good and bad horror films, and that a genre deeply embedded in the history of cinema doesn’t need a fancy laurel next to its name to make it respectable.

But something did happen in 2014, around the same time this phrase was first bandied about. The aforementioned films did reinvigorate the genre with their nuanced portrayals of grief, depression, and trauma. The Babadook was a portrait of a grief-stricken mother and Eggers’s The Witch was about a family’s descent into paranoia rather than a cauldron-stirring sorceress. Bogutskaya pinpoints 2014 as the year when introspective horror emerged, attracting critical acclaim, fostering new talent, and defining the zeitgeist between then and now.

Bogutskaya argues that this wave has simply been doing what horror films have always done: portray the free-floating anxieties of our age in extremis. Through five chapters – titled “Fear”, “Hunger”, “Anxiety”, “Pain” and “Power” – Bogutskaya traces how cannibalism and the loneliness epidemic go hand in hand, why analogue horror is the soured milk of our nostalgia-prone culture, and how body horror has been reimagined through a trans lens and become a prestige genre in the process.

Her thesis is that we are at the tail end of this wave – which is certainly a hot take. Especially as this summer was stacked with anticipated releases, from buzzy indies like Longlegs to third entries in new-ish horror franchises, namely The Quiet Place: Day One and MaXXXine. The Substance, Coralie Fargeat’s body horror romp, won Best Screenplay at Cannes and has now become distributor MUBI’s biggest theatrical release. And just last week the latest in the killer clown series Terrifier outperformed Joker: Folie à Deux at the box-office, despite only costing $3 million compared to Joker’s eye-watering $200 million. So why would this mark the end of an era?

In time for Halloween, theartsdesk caught up with Bogutskaya to discuss her insightful new book and what direction the genre is currently taking.

Why did you want to write a book about horror cinema, and why was now the right time?

Why did you want to write a book about horror cinema, and why was now the right time?

A lot of my work has been centred on horror for a number of years now, since The Final Girls began in 2016 as a screening series and then evolved into a podcast. I always knew I wanted to do something that was a love letter to horror, because it’s a genre I love deeply and a community that I feel very connected to.

When I wrote my first book, Unlikeable Female Characters [2023], I purposefully excised all horror and exploitation cinema from it, knowing that I had something else to say about horror, but I didn't quite know what it was. I learned a lot during the process of writing that book, so I eventually felt able to tackle a book that was specific about one genre, about a very contemporary moment of horror cinema. I felt firm in my ideas about what I wanted to say, and I felt it needed to come out quite soon, because I talk about the waves that have existed throughout horror film history and felt we were at the end of a particular moment.

It felt like a good time to write a book that talked about how that moment has felt, how it connected to larger ideas about horror, how those ideas have evolved, and how audiences have reacted to horror films, TV, and books. Although I don't really cover books deliberately because there's a whole other book in that!

What films marked the end of this wave of horror that you argue started in 2014?

I pitched this book at the end of 2022. I wrote it in 2023 and it came out in 2024. So the things that I felt were in the air then are kind of crystallising now. It’s a very “critic” thing to do, to find a neat period like 2014 to 2024, so I'm aware that there's a bit of me projecting my ideas onto the horror scene right now. But the horror films from that period that I write about – which really exploded after The Babadook, The Witch, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, and It Follows – are very internal, very psychological. They’re really operating in a grey area – are their characters the monsters or are they victims? These films question the idea of what makes a perfect victim on screen and question norms around who gets to be the protagonist. These films notably removed [iconic] monsters as well.

Now I feel we're entering a new horror era that's more interested in bombastic scenes and using monsters again as a selling point like they did in the 1930s. What first came to mind when you asked your question was Abigail [2024], the film about the little vampire girl that had these massive action scenes. It was like a John Wick movie! Or the Nick Cage Vampire film Renfield [2023], where the horror isn't horror, it's action - it's spectacle. This also happen in the '80s, so it’s not a bad or new thing. It’s just the temperature of horror is changing and going in a new direction. In the last year or two, I’d say we've gone back to blood lust, heightened gore. The films are less about characters, and to be slightly facetious, are less into sad monsters who are questioning their monstrosity.

I agree. The Babadook portrayed mental instability in a complex, nuanced way, whereas Smile [2022] turns trauma into a big scary monster.

Yeah, exactly. The monster in Smile is trauma literally made physical. It just feels like a full stop.

Was it difficult to hit a tone with the book that enabled it to be both specialist and accessible?

I didn't want it to be just for my pals who are professional film critics who might know all this already. I don't want it to be read just by people who feel they need to have watched X amount of films in order to be able to understand and gain something from this book. I'm not interested in appearing to be the smartest or most well-watched person in the room. The book is supposed to be both a companion and sort of a self-investigation. I'm working out my own thoughts and feelings about horror films and bigger ideas tied to what I’ve been noticing in the industry and in culture. I'm asking the reader to join me in that thinking, even though they can completely disagree with me! I've made this my job, and part of that job is to digest and communicate those ideas and that knowledge in a way that is interesting or helpful in some way. So, yeah, I think that's something that I constantly keep in mind. (Pictured below: Caitlin Stasey in Smile)

When you re-watched films for this book, did you notice things you missed the first time around or were there things you found new appreciation for?

When you re-watched films for this book, did you notice things you missed the first time around or were there things you found new appreciation for?

All of the films that I cover in the book, I watched when they first came out. But revisiting them, I definitely discovered new feelings and angles, simply because time had passed and I was a different person than when I first watched them. For example, I rewatched The Haunting of Hill House, Mike Flanagan's Netflix series, and I was struck by how much of an open wound each character is, the physicality of the horror, and what an incredible accomplishment it was to tackle a book [written by Shirley Jackson] in such a new and bold way. It could have easily not worked – but it absolutely did. That was one that I just gained completely new levels of appreciation for outside of just being scared, which I was.

There’s a low-budget indie I mention in the book that always surprises me – Starry Eyes [2014], an impeccable work that really talks to some of the ideas that I explore in the body horror chapter. I write a bit about The Handmaid’s Tale [2017] series, too. I'd [previously] started and abandoned it a few times. I was watching it to relax while writing, but the body horror really surprised me and it ended up in the book because it is 100 per cent horror. You cannot convince me otherwise. The amount of death and gore in that show is rare in TV series. (Pictured below: Starry Eyes) You draw a connection to horror films like Midsommar [2019] and The Witch with so-called “women’s films” of the '40s, such as Rebecca (1940), the film noir The Phantom Lady (1944), and Val Lewton films like Cat People (1942). Can you elaborate on that?

You draw a connection to horror films like Midsommar [2019] and The Witch with so-called “women’s films” of the '40s, such as Rebecca (1940), the film noir The Phantom Lady (1944), and Val Lewton films like Cat People (1942). Can you elaborate on that?

Women were the main audience for films during World War II and the post-war years, and so they've always been a huge audience for horror. I was watching a lot of those '40s films, and I noticed that, stylistically and on a character basis, they have many similarities with contemporary horror films in how they prioritise, legitimise, and try to present the full scope of female interiority within a genre that is excessive and not beholden to the standard rules of a world or narrative. Horror presents a playground of possibilities for female characters. That's why, over the past decade, big-name actresses, writers, and filmmakers, were suddenly seeking out these stories, as executive producers as well. They allow female interiority to be centre stage without falling into the narrative trappings of more mainstream genres like drama or rom-coms.

The Substance has been a huge hit and confirms what you write about body horror becoming a prestige genre. What did you make of it?

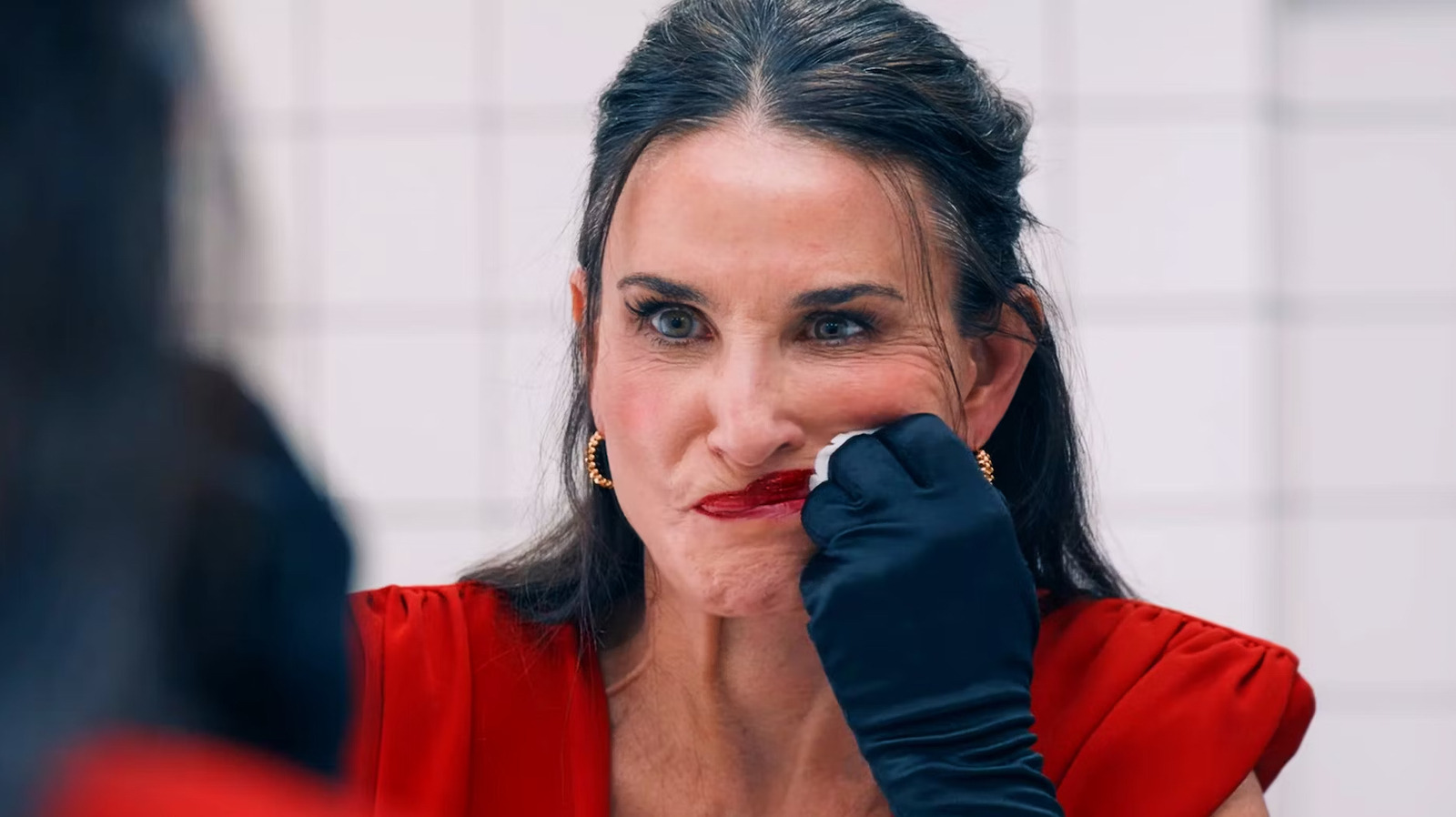

The most interesting element of The Substance is how it represents how exploitation cinema and body horror – like proper [horrror and sci-fi producer] Brian Yuzna gore – have entered the prestige space. Julia Ducournau’s Titane winning the Palme d’Or in 2021 was momentous and opened the door for more extreme, really out-there films being presented in hallowed spaces like festivals, different types of cinemas, winning awards, and even having a presence at the Oscars and the BAFTAS. It has a very small presence, but there is one. (Pictured below: Demi Moore in The Substance)

The Substance also taps into one of the most interesting horror subgenres and one of my favorites – hagsploitation, which looks into how we think about ageing and bodies, but especially how we feel about them. Of course, there’s a conflict in the culture between those who feel entitled to police and have opinions about other people's bodies, especially with female-presenting bodies, and those fighting back saying it's none of your business. The Substance is wrestling with that conflict and people have really tapped into it. Also, sometimes, you just wanna become a giant pageantry monster and explode all over everyone. And that is something that horror can do – and actually visualise.

Add comment