To the list of abiding theatrical partnerships one must surely add Tom Stoppard and the director David Leveaux. From his Tony-winning revival of The Real Thing onwards to Jumpers and Arcadia, all of which played both London and Broadway, Leveaux has proved a particularly dab hand at mining this playwright in all his near-infinite variety. And if Rosencrantz and Guildernstern Are Dead as a play doesn't, in my view, rank with much of its author's extraordinary subsequent output, Leveaux's 50th anniversary revival nonetheless does the text's unbridled energy proud. How lovely, too, to encounter it in the same theatre, the Old Vic, where Stoppard's existential vaudeville first announced this banner dramatist to the world.

This has been quite the season, in fact, for defining British plays returning to their original homes – No Man's Land pitched up at Wyndham's (its first West End perch), as did Amadeus at the National's Olivier, where it premiered in 1979. And one can only imagine what first-nighters back in 1967 made of a meta-theatrical concoction that takes Hamlet as a sort of palimpsest upon which are imposed all manner of discussion and debate that one might either classify as cod-Beckett or accept as deeply profound. In either case, Leveaux and his accomplished colleagues – the inestimable designer Anna Fleischle (of Hangmen renown) chief among them – make a winning case for the sheer theatricality of the piece, which barrels along with an elan I don't recall from the Trevor Nunn revival in the West End six years ago.

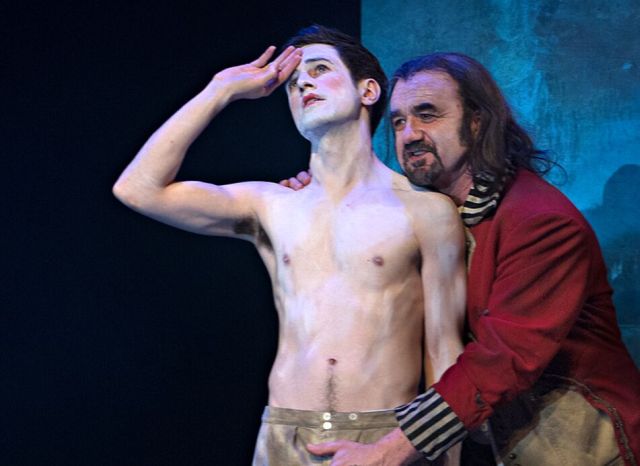

The selling card this time out is the return to the London stage of Daniel Radcliffe, appearing opposite the very actor, Joshua McGuire, who originated the role in the James Graham play Privacy that Radcliffe later did Off Broadway. In fact, Radcliffe seems a game but somewhat sidelined spectator to events dominated both by McGuire in terrific form as a questing, urgently spoken Guildenstern, and by a scraggly-haired, swashbuckling David Haig as a Player on apparent loan from Pirates of the Caribbean. Whether proclaiming that actors are "the opposite of people" or letting his hands wander to parts of the anatomy I haven't witnessed from this character before (see Haig, pictured below with a bare-chested Matthew Durkan), this ever-invaluable actor's actor is on roaring form and provides a springy contrast to the largely death-obsessed musings of the Janus-faced pair of the title.  One could make a case for a slightly recessive Rosencrantz given the character's own self-appraisal as a support act of sorts, who looks on inquisitively and open-faced as Guiildernstern charges forward, the one urging happiness as the other furrows his brow and embraces the dark that lies in wait for us all. As before, one can't help but feel Stoppard's rhetorical brio springing from the sort of late-night philosophical jam sessions that are part of youth, the writer having gone on to fold intimations of mortality far more rendingly into, amongst other works, Arcadia, where the precocious Thomasina pierces to the elemental quick in a way unavailable to the characters here. His brow creased as if in obeisance to concerns bigger than himself, McGuire has an urgency that powers the play forward, next to which Radcliffe sometimes seems to be racing to keep up. (That may explain, too, why Radcliffe zooms his way through his lines.)

One could make a case for a slightly recessive Rosencrantz given the character's own self-appraisal as a support act of sorts, who looks on inquisitively and open-faced as Guiildernstern charges forward, the one urging happiness as the other furrows his brow and embraces the dark that lies in wait for us all. As before, one can't help but feel Stoppard's rhetorical brio springing from the sort of late-night philosophical jam sessions that are part of youth, the writer having gone on to fold intimations of mortality far more rendingly into, amongst other works, Arcadia, where the precocious Thomasina pierces to the elemental quick in a way unavailable to the characters here. His brow creased as if in obeisance to concerns bigger than himself, McGuire has an urgency that powers the play forward, next to which Radcliffe sometimes seems to be racing to keep up. (That may explain, too, why Radcliffe zooms his way through his lines.)

Leveaux spices the action – such as it is – with multiply inventive touches, from the spit of Luke Mullins's fine-boned Hamlet coming back to hit him in the face to the impression that Haig's troupe of itinerant thesps can sometimes get a little bit carried away. A motley array of musicians and Pierrot figures who look ready for a good time, these players are so enjoyably roisterous that one is inclined to keep them on reserve for the next Hamlet that comes along (though I doubt they would fit in with the aesthetic of the Andrew Scott/Robert Icke production, currently playing across town).

Ravishingly lit by Howard Harrison, Fleischle's design showcases the depth of the Old Vic stage to an unusual degree. The space is marked out by a gorgeous sequence of cloud-covered rectangular panels broken up by a golden-hued curtain that bustles in and out of view with the same ebullience as a production that has taken a tyro playwright's text and unleashed, amid the angsty folderol, a lot of fun.

Add comment