The board of Sheffield Theatres has a history of appointing actors to run the show. Michael Grandage had very little directing experience when he became artistic director of the city’s three theatres. Then came Samuel West. He was followed by Daniel Evans, who had directed no more than four plays.

When the city’s theatres reopened after refurbishment in 2010, Evans (b 1973) began directing as if he didn’t wish to die wondering. Up first was Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People starring Antony Sher, and soon came Macbeth and Othello, and for his second Christmas he starred as the perpetual bachelor, Bobby, in Company. Granted, he had by then become a great interpreter of Sondheim, having won Olivier Awards for his roles in Merrily We Roll Along at the Donmar and Sunday in the Park with George at the Menier Chocolate Factory (the latter travelling all the way to Broadway).

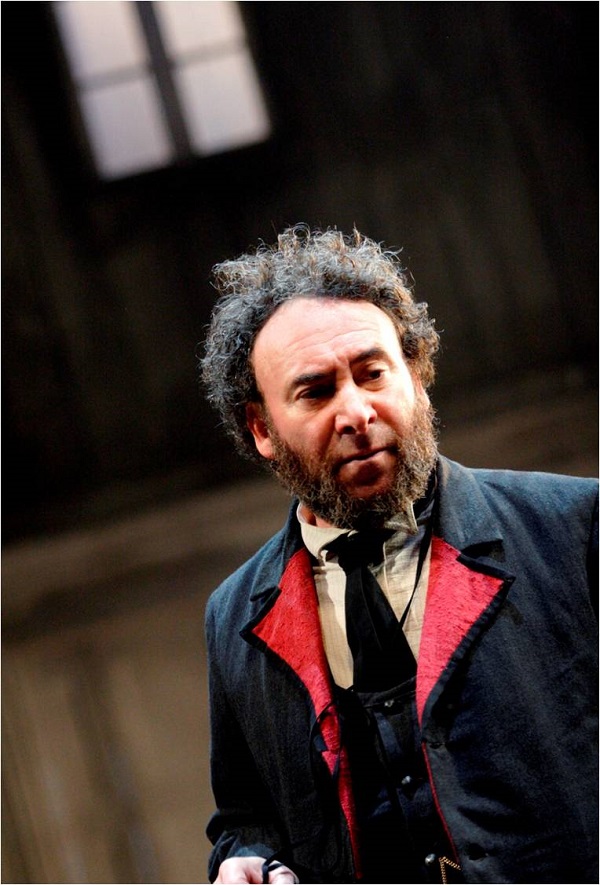

These productions excited attention in Yorkshire, but heads really started to turn in December 2012 when on the Crucible’s tricky thrust stage Evans conjured up an unforgettable production of My Fair Lady starring Dominic West (pictured right by Johan Persson) as Professor Hggins and Carly Bawden, an enchanting find as Eliza. While the most recent word was that the production awaits a rights clearance for the West End, My Fair Lady has been beaten to town by Evans’s triumphant staging of The Full Monty, reclaiming Simon Beaufoy's script from the musical version which transplated it to Buffalo, New York.

These productions excited attention in Yorkshire, but heads really started to turn in December 2012 when on the Crucible’s tricky thrust stage Evans conjured up an unforgettable production of My Fair Lady starring Dominic West (pictured right by Johan Persson) as Professor Hggins and Carly Bawden, an enchanting find as Eliza. While the most recent word was that the production awaits a rights clearance for the West End, My Fair Lady has been beaten to town by Evans’s triumphant staging of The Full Monty, reclaiming Simon Beaufoy's script from the musical version which transplated it to Buffalo, New York.

In short, we are a long way from Neverland, where Evans made his name as a gamin Peter Pan at the National Theatre when he was 25, starring opposite his idol Ian McKellen. It was shaping up to be an acting career it would be hard not to describe as mercurial. But it turns out Evans had his eye on the the reins all along. And yet the path from the Welsh-speaking boy from the Rhondda valley who won prizes at the National Eisteddfod all the way to his current lofty perch is less twisted than it might seem. Daniel Evans tells theartsdesk how it happened.

JASPER REES: The stage version of The Full Monty has come to the West End after a huge success in Sheffield followed by a tour. It’s not the first play of a film to work, but why has it in this case?

DANIEL EVANS: None of us really expected the reaction we got on the very first night. There was a huge sense of ownership from the very first sound cue - you felt the audience were within a story that somehow represented them. Also without being too strange about it there a reclamation going on. People had come to feel ambiguous about the film when it first came out, but since so much time has passed they were now able to look back with a different perspective. There was a certainly a feeling that this production was bringing the story home and that was great. What’s nice is the Sheffield audiences are able to laugh at themselves. There is a kind of wicked deadpan humour which they are very ready to deal with in most situations in life, send themselves up. There is a duality going on. People are very proud here but at the same time they are also able to give their own people and their own place a hard time.

You opened your account at Sheffield with An Enemy of the People. Why that play?

Any theatre particularly outside London has a duty to speak to and with its community, to create works that somehow challenge and reflect the values and interests of the people. It spoke to that particular time. It’s strange how time can shine a light on plays or the reverse. That was a play about how public money was being spent or being misspent and how a community go behind ideas that were in the public domain that may or may or not have been true. We had just been through the MPs’ expenses scandal. Also Sheffield is an incredible place: the values that they have inherited as a city that is a post-industrial – pride in hard work, the strength of community and having a sense of humour to get yourself through the dark times - I connected with because they reminded me of the Valleys in South Wales. That’s one of the reason I was attracted to come here. There are obvious things like proliferation of amateur theatre companies, like there is back home, strong tradition of brass bands. But also there is a strong sense of political interest. (Pictured below, Antony Sher in An Enemy of the People. Image by Catherine Ashmore.)

You can take the performer out of the Rhondda valley, but can you take the Rhondda out of the performer?

You can take the performer out of the Rhondda valley, but can you take the Rhondda out of the performer?

I think it’s TH Parry Williams who says something like, “There are bits of me that have dispersed all over the landscape.” I feel like the place where I grew up has such a strong sense of identity and values, certainly from my parents, that they remain with me. My family still live there. There is something about the history of the place and how it’s changed in the last 30 years that does stay with you wherever you go. It is a cliché to say we all sing in Wales and are all incredibly passionate, but there is something about that that is incredibly true: a strong sense of belonging.

There is a very strong sports culture in South Wales. How did that impact on you?

Drama was a kind of salvation, I think by going to the chapel when I discovered I could get up and recite passages of chapter and verse and then drama. It was definitely an escape from that rugby-playing quite macho culture which is not as prevalent these days but was when I was growing up. If you had no interest in rugby, which is certainly true of me, then you were somehow an outsider. But then drama and music is another part of its tradition. Whereas my brothers went towards sport I went toward the arts.

Was that interest nurtured at home?

My parents were both teachers and both became youth workers. They were both incredibly interested in language and literature. There were always books around the house. My father was a keen rugby player though and he still loves rugby. When the Six Nations is on the hope of watching anything on TV on a Saturday is nil. Then again our father used to sing to us when we’d go to sleep. I used to sing to my sister. There was a duality there.

What is your first language?

I’d say it was Welsh but strictly speaking I learnt them both in tandem. My mother didn’t go to a Welsh school even though her grandmother spoke Welsh. My father came from a Welsh-speaking family. Because all of my education was in Welsh including maths and science, sometimes it was quite tricky. I know all of these terms but in Welsh. Quadratic equations is hafaliadau cydamserol.

When you’re’16 and slightly in love with Ian McKellen you couldn’t get enough of it

I learnt to love language when I was younger through language and through poetry and through drama. When you have to learn swathes of cynghanedd [poetry in strict Welsh meter] you learn to love the mechanics as well as the sound. And that stuff is complex and intricate. That is something I probably wouldn’t have got anywhere else. There were great swathes of William Morgan’s Welsh bible translation that we had to learn and it’s shot through with internal rhymes and matching assonance and alliteration - it’s intoxicating. Especially when it’s done well.

How much acting in Welsh?

Quite a bit. I did a lot of TV when it was a child actor and have acted in Welsh since then. But I haven’t done much in the theatre as an adult actor.

How did your horizons first begin to expand outside Wales?

When I was at school we used to go and see whole seasons of plays in Stratford and London and I started going on my own. With school it would be a minibus or the train. With friends it would be the train. We’d go on Saturday morning, see two shows and come back Sunday. Stratford I had to wait until I could learn to drive. Then I spent most of my upper sixth going in my own.

What stood out?

I remember seeing John Caird’s Dream where the fairies were in tutus and bovver boots and Clare Higgins was a highly sexual Titania. Simon Russell Beale as Edward II in Barry Kyle’s production which again was quite sexualised. Waiting for Godot was the first thing I saw at the National Theatre, with Colin Welland, John Alderton and Alec MacCowan who I later got to work with. Judi Dench in David Edgar’s Entertaining Strangers when I was far too young to understand. One of the things that made a massive impact was Fiona Shaw playing Electra in Deborah Warner’s production at the Riverside. In Cardiff we used to go a lot to Welsh National Opera and to plays and particularly touring plays. Ian McKellen’s Richard III when it came I saw twice in a week. When you’re’16 and slightly in love with Ian McKellen you couldn’t get enough of it. (Pictured below, The Fully Monty cast. Image by Hugo Glendinning)

Why did you train at the Guildhall in London?

Why did you train at the Guildhall in London?

I didn’t get into RADA. I was given advice to go to Guildhall and had I got into RADA I might not have heeded the advice. I clearly went to the best place for me. Patsy Rodenberg’s Shakespeare lessons were just like manna from heaven. She instills in everyone her vision of how to speak Shakespeare. It’s about getting out of the way, being as open as possible to the text and not trying to foist anything on top of it. Letting the plays speak which is incredibly hard. Actors have personalities and sometimes the strength of that personality can subdue or overcome an already complex text. Sometimes it’s quite challenging to be simple and open.

What’s your acting personality?

That’s hard… I definitely enjoy a challenge. I think I’ve got quite a simple sense of humour. It’s quite tricky, isn’t it? I feel anything I say I can argue its opposite.

How about youthfulness?

Playing Peter Pan yes, because I was playing a nine-year-old and playing Candide - he was also a young man about to embark on an adventure. That became a problem because when I went to Stratford and had to be an adult as Angelo and leave behind boyish things. In life it’s not always a great attribute [to look young] and it’s not something I’m conscious of. I think it’s good to have a childlike curiosity about the world and about people. And wanting to say something about them. People say I look young. I’ve lost my hair so I don’t quite see it. But it’s not something I necessarily dislike. Having people tell you you look youthful is quite nice. Increasingly so.

Why has Sondheim been such a natural fit for you?

I came to singing later in life and remember a singing teacher at Guildhall playing one of his songs for me. All I remember thinking it was a little bit cerdd dant, a Welsh form where you set a poem to an accompaniment. The idea is you have to sing the poem as you would speak it. There is something about Sondheim’s songs that if you’re saying the right lyrics you’re almost singing the right tune. There is something if you’re an actor about singing musical thought rather than big powerful ballads. While big power ballads are great, I think I got interested in the fact that Sondheim was interested in ideas and emotions. They both go together like Sunday in the Park with George where he’s grappling with these concepts of form, balance, harmony in art as well as in life.

When you put on and starred in Company in Sheffield for one Christmas there were letters in the local press asking for your resignation. Why? (Pictured: Rosalie Craig, Kelly Price and Lucy Montgomery in Company. Image by Ellie Kurttz)

When you put on and starred in Company in Sheffield for one Christmas there were letters in the local press asking for your resignation. Why? (Pictured: Rosalie Craig, Kelly Price and Lucy Montgomery in Company. Image by Ellie Kurttz)

I think people thought it wasn’t particularly Christmassy and Sondheim isn’t so popular as a writer and so people thought that it was a vanity project. My public response was the same as my private one. This is a classic musical and while we attempt to balance the programme – the year before we did Me and My Girl and the year after we did My Fair Lady - and it seemed to me fitting that in the middle we should do something slightly more challenging. I think Stephen Sondheim is the greatest living theatre composer. Also it was important as an actor-artistic director that I put myself out there in front of our audience. And so both things came together. I was incredibly proud of it.

Is there any more acting to come from you?

Not at the moment. Partly because show planning has gone I’m concentrating on directing and running the buildings. But also partly because the parts I want to play are few and far between and they have to coincide with the pragmatic needs of the programming. I’d like to play Edgar in King Lear but the time is really running out.

Why after carrying all before you on the stage did you decide to take up directing?

I increasingly craved more creative input and creative control. I was always more interested in the mechanics of a production, how things worked and the lighting and cueing in and sound. I worked for 15 years as an actor and for the last seven I found myself wanting more of an outlet for my creativity. I’ve worked with a hell of a lot of directors and felt like I wanted to have a go. Eventually I screwed my courage to the sticking place and did a Peter Gill double above a pub in Battersea.

Did it feel like a homecoming?

Not to begin with. I think it feels like that now. There are certain things you need to practice. Directing is one of them. The nitty-gritty of being with a couple of actors. One was a two-hander and incredibly intense.

It’s one thing to be a director. Another to be an artistic director, and quite another still to be in charge of three theatres as you are in Sheffield? Why did the theatre think laterally for its third appointment in a row, your predecessors being Michael Grandage and Samuel West?

I think it’s probably a pioneering board. There is a legacy here. Actor managers have been around for centuries. You’d be surprised the directors that were once actors or who acted at university. Sometimes people become directors because they realise they’re bad actors, whereas I have to say the best directors I’ve worked with almost all have been actors. The board were clear that I would be appointed as an actor director and the actor was more experienced than the director part. It’s incredible looking back that the board felt they could take that risk. We do about 12 or 13 plays a year. And then visiting shows – around over 60 visiting companies a year.

I’m quite blatant about stealing things from people

My formative experience in theatre was going to the large cultural institutions and being in awe of them and seeing seasons of work where you could see the same actors in plays and go from the Lyttelton and then see something in the Olivier in the evening. There was something about that time when I felt I got to know those buildings when I was a teenager. The idea of being able to imprint one’s taste or to curate a season of work was thrilling even then. I was dying to get the brochure and then flicking through and booking as soon as possible - that sense of excitement I remember vividly. The acting at the time was more predominant. But when I do think back to times at school or college, it’s a partly evident by the fact that I saw so much. When at Guildhall I saw things three or four times a week much to the ridicule of my classmates who thought I ate theatre. I think there must have been somewhere in me got off on the idea that these major cultural institutions were exciting, vibrant places that contributed something to the life of the place.

Have you been tempted to cherry-pick the methods of directors you’ve worked with?

One of the nice things about being an actor is you get to work with lots of different directors. Unless you’ve been an assistant you don’t get to see that. You get to experience this whole range of how different directors work and so you can steal, you can see what works for you, what’s valuable, what’s useful, what’s conducive to producing good work. I’m quite blatant about stealing things from people. I wouldn’t say that I have a single method because each play requires something different. You put them into an arsenal of weapons so you can call on them when you need them. Not that rehearsing is warfare. It’s about generating enjoyment - that’s when actors do their best work - and the person who has taught me most about that is Richard Wilson. I’ve been directed by him twice. It’s really hard to pick people out because you really do take the best from what you’ve learnt with Grandage’s passion, Paul Miller on textual detail. James MacDonald’s mind, Trevor Nunn’s storytelling. Hopefully somewhere in there is my own person rather than a pale imitation.

You managed to secure the rights to do My Fair Lady. Why did you feel the need to revive? (Pictured: Ascot Gavotte. Image by Johan Persson)

You managed to secure the rights to do My Fair Lady. Why did you feel the need to revive? (Pictured: Ascot Gavotte. Image by Johan Persson)

Partly why one chooses to do it is because it’s a piece everyone knows and loves. I hadn’t seen the film and I still haven’t and that helps. I didn't have such a sense of that iconic version of the play. The thing is I also love Shaw and Pygmalion is a brilliant play and that’s why it is one of the best musicals written. Lerner and Loewe found a way to express those Shavian ideas through song and somehow managed to match their score to Shaw’s play in a way that is probably unsurpassed. The thrust stage was incredibly challenging. It’s written for a proscenium arch. There are clearly front cloth scenes where there are changes going on in the background. You can’t do that in a thrust because there is no curtain. That became a great feature of the production that we had to be inventive. It encouraged flow. Ours was 10 minutes shorter than the last major production and so you just have to embrace the opportunity to be inventive.

What’s your position on funding cuts to regional theatres?

I think it’s devastating. I just think philosophically it’s wrong. If you want to look at it financially for the return we give the city for everyone pound invested we return four to the local economy. Fiscally it just doesn’t make sense. For the very modest investment the return is large also in terms of what we provide the city, not just theatres but the culture in general and making this place an inspiring a pleasant place to live and what part the theatres o;play in urban regeneration. You can’t really measure those things.

Can you imagine never acting again?

I think it’d be sad. I think it’s come to a point where I would miss it.

Add comment