Jez Butterworth is back. Even before the critics have uttered a single word of praise The Ferryman, directed by Sam Mendes and set in rural Derry in 1981 at the height of the IRA hunger strikes, sold out its run at the Royal Court in hours. It transfers to the West End in June. That’s good news for British theatregoers. in 2012, the last time Butterworth had a new play at the Court, almost no one saw it: The River starring Dominic West ran for three weeks in the theatre’s tiny upstairs space. Two years later it turned up on Broadway with Hugh Jackman in the lead.

Will The Ferryman match the success of Jerusalem? Audiences as much as reviews will be the judge. Butterworth’s masterpiece was one of those once-in-a-decade, trade-a-granny-for-a-ticket theatrical events, a swearing, sweating rave with firecracker dialogue hurled in starring Mark Rylance as Johnny Rooster Byron, drug-dealing oddjobber and roustabout under threat of expulsion from his own little English Eden, a ramshackle trailer in a patch of Wiltshire woodland. It was so great that even Nicholas Hytner in his new memoir admits that it should have won the Tony Award for best new play over the National Theatre’s War Horse.

More than any of his contemporaries, Butterworth is a playwright who fires up excitement. His last appearance in the West End was a revival of his 1995 debut Mojo, a gobby portrait of turf warfare on Music Row in the late Fifties which found seasoned critics reaching for superlatives. But who is he? And what is the soil out of which his work grows?

He was born in London in 1969, but grew up on a housing estate on the edge of St Albans in a house jostling with argy-bargying males. Seven years divide Mojo and its successor The Night Heron, which configured memories of Varsity with typical angularity via a pair of oddball college gardeners. Later came The Winterling, featuring runaway gangsters on Dartmoor, which may as well have been called The Pinterling, in homage to the playwright who became a kind of mentor (his other lodestar being Mamet).

In a long and revealing conversation, Jez Butterworth tells theartsdesk how he built Jerusalem and other worlds.

JASPER REES: What are your memories of Mojo the first time round?

JASPER REES: What are your memories of Mojo the first time round?

JEZ BUTTERWORTH: It was really really really fun. It was really really exciting to do. It felt like every time you saw it it was so hot. It had loads of heat and it also contained some light as well. It was that that I was always trying to recapture.

How old were you when you wrote it?

25. At the time it felt like it understood something about the presence of theatre that you don't see every day. It understood how to put something in front of you and make it theatrical. It understood why it was a play. It’s why turning it into a film was such a folly. But it really was a play. That’s what I remember about it, is that it was a play.

When you were making the film did you think, this is a play?

Yeah, totally. There was only one thing that happened in that film that I believed and it was the scene with Harold Pinter at the end where he’s trying to seduce Hans Matheson and it was electric. Absolutely electric. It felt completely different. Everything else felt meretricious.

Did he know it was a play?

I don’t think he necessarily did. But he had different distinctions between what a film was and what a play was. We share loads and loads of opinions but I don’t think we shared that.

How did you know how to write a play that knew it was a play? Was it guesswork?

A lot of it was just following your nose and feeling that, well this works, and this works. You realise after a while that’s all you’ve got. You can just push it forward in places that excite you and not really ask why. I write so differently now, that’s the thing. At the time it was all rhythm, it was all about rhythm and sort of screw everything. You’re talking about the rhythm of a line, you’re talking about the rhythm of a scene, you’re talking about the rhythm of an act. Like, I’m just watching the rhythm of it. Scrub that. I write in exactly the same way. I do exactly the same thing. That hasn’t changed at all. It’s just that. That’s hasn’t changed one bit. That is my compass.

But where did it come from? Were you a theatregoer as a child?

No. Up until going to Cambridge I had been in four school plays. I had probably seen four plays in my life. And then, yeah, I went to Cambridge specifically to do plays. I had seen a play that my brother had been in and it seemed so exciting. And it was amazing. I still get excited thinking about it now. It was just thrilling. It was like the thing I wanted to do.

Did you go up to act?

No I went up to write. It said on my form - because they ask you, don’t they? – it said, what do you want to be? And I wrote "writer" on the blue form that you apply with. I knew that was what I wanted to do. And then I went to act and I went to direct but I already knew that all I wanted to do was write. I had written nothing.

So what did you actually officially read?

English.

Did you do any work?

No. I had a really forgiving director of studies who knew what I was about. I think I might have been honest with him up front and said, “Look, this is why I am here. I want to do this.”

And he didn’t arrange for you to be sent down?

No he didn’t. Tom Morris who [co-]directed War Horse was one of my tutors there and he told me that they were going to throw me out and that Tom made a special plea on my part to get me to stay because he said that I was really really really working. I was just not working hard at the course. He said you’d see me running about from audition to play to... I was working really really really hard. Just not at anything academic.

Did you get a third?

No I didn't. I got a 2:1.

You see? You didn’t need to work.

Yeah but in the last month you can always pull it out the bag, can’t you?

When did you write your first play?

At university in my second term when I was 19.

Any good, for the time?

It was all right actually. It went up to Edinburgh and it sold out. It was called Cooking in a Bedsitter. It was an adaptation of a cookery book, a verbatim adaptation. Every single line in it came out of a cookery book. It was just made to... people were just saying lines from this.

So it was like a found play.

It was, yes, and also it excused me of having to write any lines. It was quite cleverly thought out that way.

What happened with the next plays?

I did a couple more... I did another one of them. I literally did the same thing with a different book. And that didn’t go anywhere. And I wrote about four plays at university which were all like sketchy type things. I wrote a play called Huge that was on in Edinburgh in ’93 with Ben Miller in it and Simon Godley that was made into a film. But I had nothing to do with it. I had five or six brushes with lights going down, my work starting in Cambridge, in Edinburgh, in various places, one at the King’s Head before I realised that I had to try and write something in a longer form, that I had to try and ... I sat down to write Mojo, I wanted it to go for an hour and stop, and then an hour and stop. You’ve got to sustain, you’ve got to be able to keep it... There will be something about that that will make it better, that will be harder to do, that will require more of everyone.

Did it change your life?

Yeah it did, it definitely was. In good ways and in disastrous ways. I think that I hadn’t really planned beyond it. That was the problem. It was like a failure of imagination to not plan beyond. I was like I say 25 years old at the time and I didn't really have a big plan beyond that. Looking back I can see that now. It wasn’t like, "OK I’ve done that. Now I’ll do this." It was seven years before I wrote another play.

Can you put your finger on why that was?

It’s because I didn't have a plan beyond it.

But inspiration may still have struck.

And I wish it had but I don't think I knew where it had come from in the first place. I still don’t. It’s the big thing that I know about this game, is that you just don't know where it’s coming from and when.

You can see almost a jagged kind of daisy chain in the canon of your work. But correct me if I’m wrong, Mojo doesn’t really belong to that daisy chain.

Well I think you can only say so in terms of the fact that it’s located in London. I think that it does belong in other things. It takes place in one location, there’s only one set. I’m never constantly changing the set. It takes place linearly over time.

So you observe the Greek unities.

I think I do.

What are they called? Time and place and what’s the other one?

I don’t know. If I’d studied when I was at Cambridge I would know that.

So what did you do in those seven years?

I got into trying to make films and writing films. I got very lost actually, very very lost indeed.

Was that a sort of flowery bower that was a temptation that you should haven’t been lured into, or did you go into it with a view to doing good work?

Look, I adore film. Film is my first love as well. I had seen 10,000 films before I had seen one play. I’d seen everything John Wayne ever did, everything Paul Newman ever did, everything Steve McQueen ever did. We sat and we watched them all the time. It’s in my blood in a much deeper way in some ways than theatre ever is. If you just talk about hours spent watching film compared to going to the theatre, it’s a thousand to one. So it was something that I absolutely wanted to do and always wanted to do and always will want to do. It’s like a real passion of mine. I love that I’ve got two passions, and two different like, as it were, forms of the game. Actually no, they’re not even the same game. They’re both with a ball. They’re like cricket and football, you know, but to be able to play both is such a blessing. It really is. And I love going from one to the other and I find that if I move from one to the other I’ve got twice as much energy as I thought I would have rather than half of it.

The thing about football – and we know which one of those art forms is cricket – is that you have to make so many more compromises. It’s much harder to achieve realisation of whatever it was that you started with.

I think so but it really depends. When I wrote the version of Jerusalem that everybody saw, I wrote it at night in New York whilst I was producing a film I had written with my brother John Henry during the day. So I’d get up – you know what it’s like in films. You get up at five am, you go to the set, you’re there until like 11 at night after rushes, and then you come home. So I wrote Jerusalem between 11 o’clock at night and five o’clock in the morning over a period of about a month before we started rehearsing. It never felt like I was tired at any point, either on the set or at night when I was writing the thing. The fact that you were doing both at the same time just felt like you were using different muscles so you couldn’t get tired. They sort of fed each other in a way that I don't really understand. They both were under tremendous time pressure. It felt like a performance in a way. It felt like you had to deliver in both areas. And I suddenly looked up one day and from this balcony I was like, “How do I fucking end this play?” And I just felt such joy that I was involved in this. I was working with Sean Penn and I was working with Mark Rylance in the next week and I just sat there and I was like,"This is brilliant, this is what I wanted to be doing." I literally wanted to have this time problem. I wanted to be double-booked, as it were, to do these two things.

Where have you done your best work?

I think without a doubt so far in terms of the things that I’ve created that I am always going to be proud of, in the theatre certainly. My ambition in film is to try and work out what ... I think I’ve worked out to some degree what it is about theatre that makes people go, how did they do that? I don’t think I’ve quite worked it out in film. It’s brilliant to have that as a place to learn.

You’ve done a lot of script-doctoring. Is there any reason to do it other than it pays well?

Yeah there really is. You get to work with... it comes back to the thing that I said. Your average film takes seven years from beginning to end. It’s just so long. I love the fact that I can basically go on holiday to other people’s films, get all of the excitement, and all of the pressure, all of the angst and the how do we solve this and how do you really make this story work? But I can do it for two weeks rather than seven years. I love it. I get excited showing up to do it. I find that it is such a respite being given a different set of problems to deal with and one that you’ve got technique to play. And those techniques are hard-earned, you learn them over a long long period of time, and you can really apply them like a doctor. Literally it’s called script doctor. You turn up and you can tell what’s wrong.

Is it always to do with structure or are you sometimes just asked to come in and sort the dialogue?

Yes. It really depends. It depends how late you come in. If you come in very late then often the structure’s defined. You can still do a tremendous amount. Like you can do something in three seconds of a screenplay that changes the entire meaning of the thing. I absolutely love it. I adore doing that. It never ever feels like drudgery. I was a terrible actor and it’s close to a performance. It’s like you go in and the lights go up and you’ve got to deliver. It’s like taking a penalty.

It’s a cameo role.

Yeah it is, and if it was all I did we wouldn’t be talking to each other.

Is that as close as you want to get to blockbusters?

Yes, and it’s a brilliant place to stand. It’s great fun. I would have gone to see those films when I was 14 years old and I would have been sitting there thinking, this scene could be better. You wouldn’t have said that. If I’m driving to the airport out of New York and I’ve done a play in New York, the further you go out to the airport you’re thinking, these people aren’t going to the theatre, they’re watching the films. They’re going to go and see Snow White, they’re going to go and see the James Bond. I feel better the further I go out there, because I’m doing that as well. I’m rewriting all of those films.

Was it in that seven-year period when you say you didn’t write a play that you upped sticks and moved to the country?

No I upped sticks in 2005. I’d already written a second play before that. The Night Heron. And that reminded me how much I really really loved the theatre.

How hard was it to drag yourself back to the theatre? Did you really have to drag it out of yourself?

I was desperate to do it. I had lost all confidence. I had lost all my confidence. And I had no connection with a theatre. I had lost touch with the Royal Court. Ian [Rickson, the director of all Butterworth's plays] had already been artistic director at the Royal Court and we hadn’t seen one another.

So you were living in London.

Right, and I hadn’t bothered to go down to Sloane Square and say, “Congratulations, Ian,”

Why not?

I was marooned.

What did that mean in practical terms?

It meant that I was terrified...

Of the fact that you might be a one-hit wonder theatrically?

Very much so. And also I had no idea... I felt responsible in some way for what had happened, and that was the mistake. As soon as I didn’t feel responsible for it then it showed up again.

You felt responsible for the fact that inspiration appeared to have wandered off.

Yeah it’s embarrassing. It really really was that. You should have asked me at the time. I would have torn up beermats and changed the subject. But it absolutely was the case that I was completely, from my background and from how little I’d had to do with theatre, it was the most wonderful event that I turned into a personal calamity by just not hanging around the theatre any more. I should have just stayed there.

Did you go to plays?

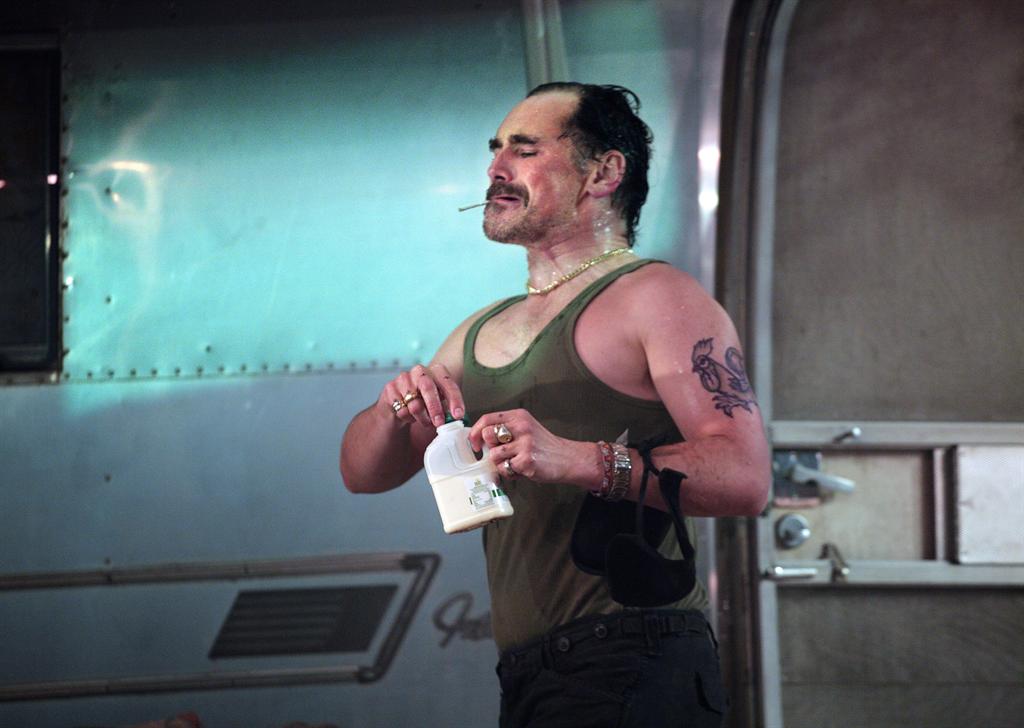

No. No. It was like I was just completely... I went into film. And I would go and see films and I’d spend a lot of time on aeroplanes. Pictured above: Harold Pinter and Ian Hart in Mojo.

Pictured above: Harold Pinter and Ian Hart in Mojo.

I directed him in 1997 and he really became a mentor for me about 2005, I think because we didn’t see each other for ages and then I went to have lunch with him and then we started having lunch a lot.

Why did you go and have lunch with him?

I don’t know. I guess for all the reason we’re talking about?

But how do you go and have lunch with Harold Pinter?

I actually can’t remember how our paths crossed again, but he did say to me, “Why haven’t you been in touch?” And I was like, how do you have lunch with Harold Pinter? It’s exactly what you said. It’s like, “How can I call you up and say, ‘Let’s just have lunch?’” and then we started having lunch all the time.

Do you think you hadn’t been in touch because you were embarrassed about not having written another play?

Very much so. What would I be saying?

And did he ask you that?

No he didn’t, he didn’t. He did a really kind thing and I don't think he meant it to be kind, because you treasure someone like Harold for his honesty rather than his kindness, though I think he could be amazingly kind. When I wrote The Winterling which is a play that sounds a lot like Harold Pinter, he was the first person I sent it to to see what he thought of it, and he was so positive about it. He just loved it and he didn’t see for a moment that it sounded like him even though it did. He didn’t spot it at all, which was sublime in a way.

Did he not spot it or did he just not say?

I will never know, but I do think that we knew each other well enough or him to have said, “Do you know what? Don’t do that.”

But he didn’t.

He didn’t. He didn’t.

Is it coincidence that it was that year that you moved to the country and seemed to reengage with theatre?

As I was writing The Winterling, the Royal Court were having their 50th anniversary and they had a slot. I think Caryl Churchill pulled her play because Tom Stoppard was doing Rock’n’Roll or something. I think that was it. And so suddenly Ian called me up and said, “We’ve to a slot for downstairs. Have you got an idea for a play?” I said, “Yeah, I’ve got an idea for a play.” And I told him all about it and he was like, “Great, give it a crack.” And that night I sat down to watch Harold Pinter’s Noble Prize speech, Truth, Art and Politics, I think it was called – and in the first 20 minutes of that he tells you how to write a play. And it spoke to me. I hadn’t seen him for a while and it spoke to me. And I sat down that night and I thought, right, I’m going to write this play that I told Ian about. And I wrote a completely different play.

Boil down,if you could, those first 20 minutes and say, what were the precepts that you took from his Nobel Prize acceptance speech?

He says, “I start with Character A and Character A says something. He says, ‘Once it was dark.’ And the other character says, ‘Yes, dark.’” Or whatever the beginning of Old Times is. And he just knows that he’s in on something. He doesn’t know where it’s going. And I believed him. I actually believed him. So I just sat down in the dark, I lit a candle, and I had a first line and I just followed it where it was going next, and it was just so amazingly fun. At that point I was consciously aware... I was, I think... Christ, Harold’s sitting there in a wheelchair, he can’t even make it to Sweden for the thing, it looked like he was literally about to die. So when I started writing that thing, the fact that it sounds like him is just an elegy to how much I loved his work and how much... it was like picking up a trumpet and trying to play something like Miles Davis. It’s a completely honest and, I think, valid thing for anyone to try and do. And that’s literally what it felt like. And it was almost like the more it sounded like him, the better. It really felt like that. Cos it’s not easy to sound like Miles Davis.

The play riffed on your knowledge of living in the countryside. Was there any part of moving to the country - the isolation, the fact that it’s miserable in winter - that you regretted?

None. Not any part of it.

Because you were very poor.

When I first moved to the country, when I moved when I was 25 - because I’ve moved to the countryside twice. When I first did that we were broke as could be. I was living with my brother, we were living out there together.

Which brother?

Tom, my older brother. We moved to Pusey which then became the village in which Jerusalem is set. I never expected that. I didn’t realise I was there for two reasons: that I was going to be writing Mojo and that 15 years later I was going to set something there. I didn't realise that at all. But there’s not been a second where I was living in the countryside where it felt like the wrong place to be. If I’m in a city or if I’m in the countryside, they are imaginary places for me. They’re like dreamscapes. It’s just the way I think. But I don’t really draw much distinction between the city and the countryside, but I do know that they are differently stimulating and that’s the important thing for me. It’s always been the way.

The business of keeping animals and slaughtering your own: does that have a spiritual side?

Very much so.

Or is it case that you need to eat and someone’s got to kill them?

No it’s entirely the former. I’m thinking back to The Winterling now. That is a merciless play until its last scene and there was something about the act of keeping and raising and slaughtering animals that astounded me, that if anybody else did it might not astound them. Hemingway didn’t see much war but the amount that he did see had a tremendous effect on his work. I haven’t killed that many animals or been that great a farmer but it’s had a tremendous effect on the way I see the world. I couldn’t believe that you were allowed to do it. It’s just extraordinary. You take these creatures in the dead of night who are as big as you and you drive them through the fog and they kill them in an alley and then you watch them, if you are allowed, just get thrown into a boiling bath and all their bristles scrubbed off them and you can still see which one’s which that you’ve spent all this time with and you’ve seen them since they were this big, and then they are disembowelled and eviscerated and the next time you encounter them, which is about a week later when you go and pick them up, they are meat. And then this whole other process begins where you turn it into everything you can think of. But it was such an affecting and visceral experience. About the fifth time I did it I started taking people along and some couldn’t bear it. They were like, “This is the most outrageous... someone should put a stop to this."

Were there people at the abattoir thinking, metropolitan pansy poet?

I couldn't give a fuck. If that was the case I couldn’t a fuck. I don’t have that level of... I don’t care about myself in that kind of a way. I’m sure there were. There’s a character in Jerusalem, isn’t there, who works in an abattoir who kills hundreds of cows every day and he doesn’t give a monkey’s. He would have thought I was a cunt.

Did you put him in for that reason?

I put him in that play because there is a still point, isn’t there, at the heart of any play. In that play which is about change – I think, I now realise, it’s about accepting change and how hard that is. It’s lovely to have a character at the heart of it who doesn’t want to go anywhere.

Was moving to the country a second time a change for you?

Enormously so, in that I felt presented with all of the things that I wanted to try and deal with. You feel presented with them. You’ve got no distractions. You can’t hide suddenly.

There is this perpetual focus in newspapers on the dividing line between town and country. You’re saying it’s less of a relevant distinction.

There’s more time in the countryside. There was less time to meet up with friends and go to the pub and more time to walk a dog along the river and if you’re a writer you better start spending some time thinking about stuff other than not.

Did you actually move to the country in the end, when you strip away everything else, to write?

Yeah I did. I think so. That was suddenly apparent when I got there.

And why did you need to go there to write?

Because I was completely marooned in London.

Stuck on an island with no way of escape?

That’s what it felt like as a writer certainly. It was that I couldn’t ... I had a sense that ... that there was something beyond how far I was willing to push it, that there was something beyond that, and I needed to know what that was, and I wasn’t going to find it doing what I was doing.

And what were you doing? You’d written Mojo.

I was distracting myself. I was getting by on technique. I was essentially a session musician. You know, I was just showing up and I could play and then I could go home and forget about it. That was what I was doing.

Why can’t theatre be like Jerusalem every time? Because it’s too big a bet. Because the stakes are too high. If you go along and see a boring film it’s fine, you can probably get something out of it. If you go along and see a boring play or a badly made play or, worst of all, an embarrassing play, it’s excruciating. It’s asking something of you. If you walk into a matinee of an arts cinema and you go and see Last Tango in Paris and you’re the only person sitting in the audience it’s wonderful because you can spread out and you can enjoy it and you can experience the film. But if you go along to see a matinee of Macbeth and you were the only person in the audience, as soon as the lights come up you are going to feel excruciatingly put on the spot, aren’t you?

Because it’s too big a bet. Because the stakes are too high. If you go along and see a boring film it’s fine, you can probably get something out of it. If you go along and see a boring play or a badly made play or, worst of all, an embarrassing play, it’s excruciating. It’s asking something of you. If you walk into a matinee of an arts cinema and you go and see Last Tango in Paris and you’re the only person sitting in the audience it’s wonderful because you can spread out and you can enjoy it and you can experience the film. But if you go along to see a matinee of Macbeth and you were the only person in the audience, as soon as the lights come up you are going to feel excruciatingly put on the spot, aren’t you?

Fairly extreme example if I may say so.

But you know, it makes the point that being present in the theatre with the actor asks a different thing of you. Marlon Brando doesn’t know that you’re the only person in the audience but the actors do. That says it’s a big bet.

How many times do you reckon you saw Jerusalem with an audience?

Um, 20 I think. Around 20.

Was there a point at which you thought, actually I don't need to see this tonight?

Never. Never. No. I looked forward to every single one of them and there wasn’t a single one of them where it felt like I had to, whether it be the Royal Court, whether it be the West End or Broadway. It always felt like you were showing up... I mean it’s such a brilliant part of the day to keep busy – eight until about ... It's a great time to be doing something. If you go to dinner it’s great. It’s a brilliant piece of the day to fill with something like that. I always look forward to it. You’d look forward to it all day if you knew you were going to see it. And it would always be different.

You started Jerusalem in 2004, didn't you?

Well, to be precise, there isn’t a thing written on Jerusalem that I would wish to hear in theatre before about March 2009. Previous versions of that play do not contain anything that was in the final version.

A single line?

I reckon maybe nothing.

Even the name of the main character?

Oh yeah, that was probably the same.

Which is a great name.

Yeah, it’s good.

When you hit on that name, did you think, that is a name you can build a play around?

I still to this day can’t even remember having the idea for the name. But that’s his name. Names are funny things.

Why does it take so long for a play to percolate?

The closest I could get is to do with the belief I have that they don’t come from you in the first place. They are sort of coming through you. And so all you need to do, you need to be patient. You can’t blame yourself for that – you just need to sit and wait. You can’t panic your way into catching a fish. You can’t foist it upon the river that it suddenly should give you your due. Even if you’re good at catching fish you can’t go, "Hang on, I’m good at this shit. Where are all the fish?" You can’t do it so you have to sit there and you have to wait, and sometimes you have to wait for years. Sometimes you die waiting. But you’ve got to wait.

Can Jerusalem be seen as a Christian allegory and Johnny a Christian martyr?

That’s rather wonderful and I think you could make a really really strong argument for that. I think it’s crucial that that was never my intention. I got a letter from a Spanish woman who came to see the play who said that the last time that she was naked, covered in blood with a drum beating in her ears waiting to meet giants was when she was born. It just really struck me though if I’d intended it to be a literal birth it would have been a disaster, but the fact that I didn’t intend it but it’s there is really really speaks to what it is when you’re trying to create something like that. It’s not up to you. You’ve just got to want to do it and do it as honestly as you can and be fearless. But you can make an argument that it’s the George and the Dragon myth – I’ve realised that fits perfectly even though I didn’t even know it. It’s all there. It’s just not intended.

Are you able to put your finger on what was your intention or is it dangerous?

No you can put your finger on it. My intention was to follow one thing and one thing only, which was a physical reaction that I would have to the material that I was creating. Namely just whether or not you went cold and you got goosebumps. If that was happening while you were writing, if that was happening then there was every chance that your body and your blood and your guts knew something about what was going on that you didn’t, and if that was the case there was every chance that an actor would feel that, and then there was every chance that an audience would feel that. That’s the register that I want these things to be in. I don’t care about anything other than that in terms of my writing I don't care about anything other than that. It’s got to be in that register. It can be in any form. It can have no words in it. It can go on for five days. It can take 10 seconds so long as it’s in that register.

And will you submit the play if it’s not in that register?

No, never, ever, ever.

Have you in the past?

No I haven’t but there’s definitely without doubt been whole bits of a play like The Night Heron has a big fallow period in it where there’s nothing going on, where it’s not plugged in in that kind of way. And I remember sitting there watching and thinking, where’s it gone?

You didn’t know it at the time?

No I didn't know it at the time. I didn't know.

When you handed in Jerusalem, when you gave Ian the script, on day one in how much shape was the script and how much happened to it?

OK it had its essence on a plate. It was right there. It was all there. What it needed and this is why I love rehearsal and why I love the Royal Court and how trusting they are, is that I knew, like opening a bottle of wine I knew it needed air, I knew it needed to be in a room with actors. We told them that we would change anything if it felt right. The thing that I’m describing you, like following the bit where it sets your skin on fire, what if you hit a bit where it’s not? I had just to keep changing it in the room over the first two weeks so that it was more like and more like that. And as such it arranged itself in I think quite a dramatically different way. A dramatically different way. But nobody has ever written a word of that play except me, but I took it into the room with them in such a free and open sense that everybody felt that even if they put their hand up and said “I don’t understand”, they felt they were contributing. Sometimes even by their presence they were contributing.

When you saw what Mark Rylance was doing, did that influence you?

Well, I’ll tell you where he influenced me most of all was in my house by the fireplace late at night the first time he came around about a month before I wrote it, when he read a Ted Hughes poem aloud. Talk about goosebumps, it was ridiculous. It was like this guy can ... I’d always loved the poem, it was a poem called “Daffodils” from Birthday Letters, and he read it in such a way that I will never forget. And I went to sleep that night thinking that there is a register here that if you can hit it he can do it. You’ve got to try a hundred million times harder than you thought you were going to try. That’s to describe inspiration. Literally being inspired by someone: you meet them, you go, "They can do this: I want to play, I want to provide." And so Mark was in that respect totally the inspiration for it. If he’d never acted in it after that, he would have been the defining thing about it.

What was it about that poem? The poem itself or the performance?

The important thing about it is that I was listening to it. Anyone else might be listening to it and they can’t turn it into a play. The point is I was listening to it, and I responded in that kind of way. But it inspired me. There’s inspiration and there’s who’s being inspired.

What’s the overlap between you and Johnny Rooster Byron?

We have the same initials. That’s it.

Seriously?

Now I think the seven years I spent in the pub that we talked about inform entirely what Johnny is up to. He’s sitting around shooting the shit and he’s trying to keep the ball up in the air and he doesn’t want everyone to go home, he doesn’t want to be on his own, ever. So without that period that we talked about you literally do not get that play. If I didn’t know ...had I known what I was doing and had I woken up the day after I finished Mojo and thought, "Now this is a career path, this is how you do it, you’ve got to hang around the theatre," you’d never ever ever get that play.

How unwittingly were those seven years research?

Very much so. It’s all over that thing if you look at it. What was so disastrous about its first iteration was that I wanted to know. I wanted to make it about something. And then I sort of abandoned it in some period in between and sunk a lot deeper into what I wanted my theatre to be like, to taste like, to smell like, to sound like. And so when I returned to it I never asked myself any question about it at all. It was happily on an entirely instinctive level. Entirely. and so all of those questions, the fact that it is about England, the fact that it’s got that political resonance or whatever is purely by the by. I can’t really say why that’s there other than I’m English and I spent a lot of time staring out of train windows thinking about the land.

Your father landed on Omaha beach on the first day of the D-Day landings. Did that cast a long shadow over your childhood?

It defines us as a family.

Can you explain why?

Yes I can. I think my dad was afraid from that day on. He was in shock from that day on, and he did his sweetest best to raise a family in the light of what was profound, profound trauma that it took even 50 years to even talk about. And so you grew up in an element, like fish swimming in the sea, you grew up in this element of anxiety and fear.

And you didn’t know what it was about?

No idea.

Did your mother know?

I don’t know. I think she knew what his experience had been. She didn’t know the nature of it.

So in 1994...

In 1994 he starts to talk about it.

Why?

He started to talk about it because my brother John Henry came home one day in a bright red duffle coat and it was a horrible duffle coat but my dad took one look at it and started to shake because that morning on 6 June 1944 he had been issued like all the leading seamen with cream duffle coats which by the end of the day were bright red with blood from clearing up body parts off the beach. And he hadn’t seen that item for 50 years. And suddenly floodgates just opened, absolutely opened, and he started to talk about it. And he started to talk about it in a way that we found incredibly hard to cope with because we didn't talk about things like that in our family. We didn’t. We do now.

How long did he talk about it for?

He would blurt. It would come up. You’d suddenly start and he would get very upset and we would get very shocked. He should have had mounds of therapy to get him through it and it never happened. He told me things that were just unbelievably shocking.

And did it explain for you the atmosphere of your childhood, or was it the artist in you that chose to explain it the way you have?

It’s bound to be the second thing, it’s just bound to be. My perspective of how I grew up is almost entirely, I would say, factually inaccurate. I’m sure. I’m pretty much sure of it. Were member the things that we need to remember.

Do you think that that atmosphere whether it happened or not – has that informed you as a writer and if so can you say how? It can’t be a coincidence. You’d already said on your blue form, "I want to be a writer." A year later you wrote Mojo.

I would say this, if you look at people who write and who consistently write, they tend to have enough stuff that’s gone on in their past that’s strange and unknowable and unquantifiable to them to get by. I can’t now go to my mum and complain about anything that happened because I would have to go and get a job. Do you know what I mean? There tends to be, and it doesn’t have to be big, there tends to be some sort of trauma in those people’s past. When I say it’s inaccurate, it comes back to the Hemingway idea. Hemingway will tell you that he was on Omaha beach too. No one really knows whether he was. It’s like he saw a little bit of war and it had a tremendous effect on him. It’s important to accept that the second you write something down, the second you try and dramatise it, what’s actually true about it becomes irrelevant. It’s about capturing its essence. Picasso says, “Art is a lie to tell a truth.”

- The Ferryman is at the Royal Court until 20 May then transfers to the West End

- Read more theatre interviews on theartsdesk

Add comment