The Bauhaus school and its subsequent influence make an extraordinary story, and this film by Mat Whitecross, which has assembled a whole range of different voices and perspectives and woven them together, told it well.

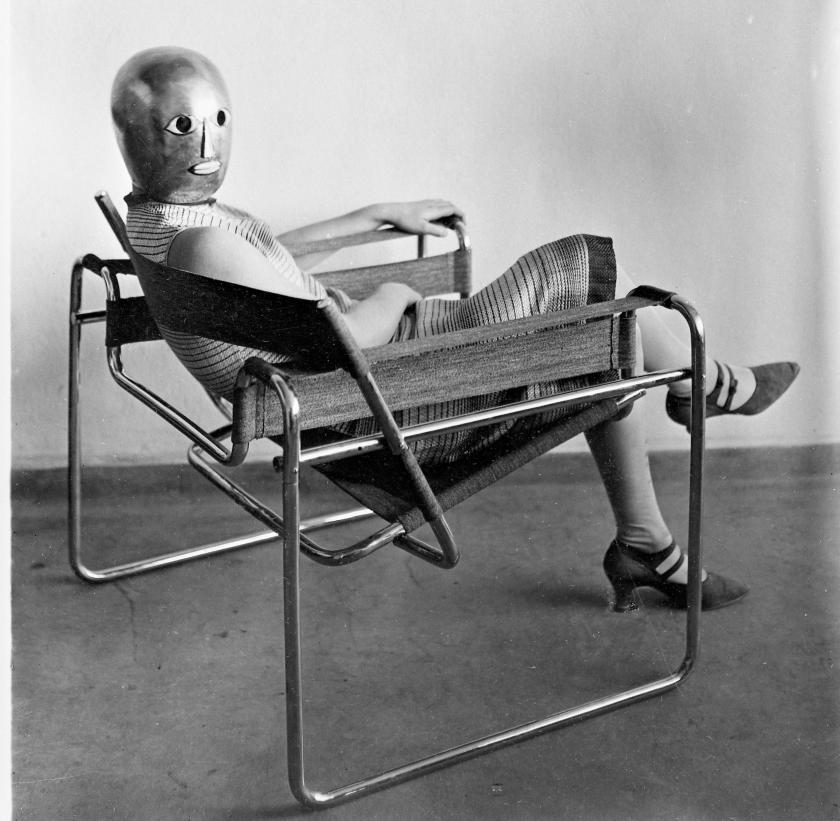

As a school, the Bauhaus lasted just 14 years from beginning to end. It opened in 1919 when Walter Gropius was finally able to accept an invitation to merge the art schools of Weimar and to be the principal of the “Staatliches Bauhaus”. The roll call of star teachers which Gropius attracted to Weimar was impressive right from the early years: Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer. It stayed in Weimar until 1925 when a political shift in the city obliged it to move on. There was a phase from 1925 to 1932 when it occupied its iconic Gropius-designed building as the “Hochschule für Gestaltung” in Dessau (pictured belowand then just one year from late 1932 until July 1933 as a private school under the leadership of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, described as "a master architect who can draw like a God", in a disused factory of Berlin-Lankwitz, until the Nazis moved in, seized it, and forced it to close. The multiplicity of perspectives through which Bauhaus 100 told its story gave the film genuine richness and quality, and yet the pacing and the consistency of the narrative thread worked very well throughout. The first speaker in the film, Michelle Ogundehin, initially took on a straightforward role as cheerleader for how significant the legacy of the Bauhaus has been, as in “it changed the world forever,” but was impressive later on the subject of colour. Neville Brody and Deyan Sudjic were persuasive on the decisive influence of the “form-follows-function” principle in industrial design, and looking at how Bauhaus educational principles have become embedded in the English-speaking world, and also pointed out the way the Bauhaus inherited and incorporated the British Arts and Crafts movement. Gropius’ biographer Fiona MacCarthy and other speakers assessed the sheer scale of Gropius’ vision, mission and his “talent for self-publicity.”

The multiplicity of perspectives through which Bauhaus 100 told its story gave the film genuine richness and quality, and yet the pacing and the consistency of the narrative thread worked very well throughout. The first speaker in the film, Michelle Ogundehin, initially took on a straightforward role as cheerleader for how significant the legacy of the Bauhaus has been, as in “it changed the world forever,” but was impressive later on the subject of colour. Neville Brody and Deyan Sudjic were persuasive on the decisive influence of the “form-follows-function” principle in industrial design, and looking at how Bauhaus educational principles have become embedded in the English-speaking world, and also pointed out the way the Bauhaus inherited and incorporated the British Arts and Crafts movement. Gropius’ biographer Fiona MacCarthy and other speakers assessed the sheer scale of Gropius’ vision, mission and his “talent for self-publicity.”

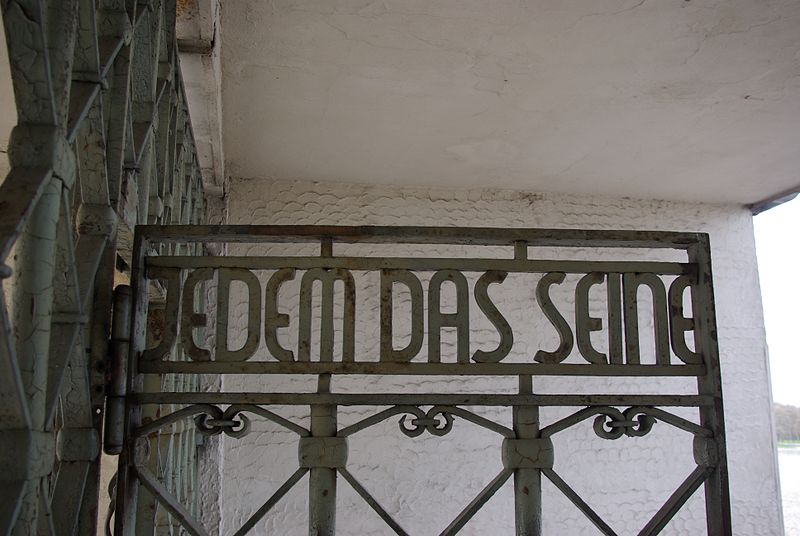

The episodes which brought to the fore, for example, teacher Johannes Itten’s dangerous fascination with the fire cult Mazdaznan, and Hannes Meyer’s rigid adherence to Marxism, equally perilous for the survival of the Bauhaus at the time, were vividly portrayed. A sceptical Tom Wolfe and his pale suit also popped up briefly. Other speakers pointed out ironies: although the dominant culture at the school was left-leaning, the gates of Buchenwald with their inscription ‘Jedem das Seine’ (To each his own) was designed by Hans Ehrlich in a Bauhaus font (pictured below) and the barracks at Auschwitz were designed by a former Bauhaus student. And then there were the parties... A fascinating aspect is the presence of considered and authentic voices assessing their own pasts. Gropius himself, from the splendour of a post-war professorial chair in Harvard, assessed and constructed his cultural inheritance eloquently and carefully. “The idea was to mix up these things to see that there is no barrier between a painting and the other things of our environment... I consider beauty a basic requirement of life.” There was a tantalisingly short intervention from the quiet but crystal-clear voice of Josef Albers, who more or less summarised the whole history of the school in one well-turned sentence: “In Weimar it was a state institute, in Dessau municipal, and in Berlin we were a private institute.”

A fascinating aspect is the presence of considered and authentic voices assessing their own pasts. Gropius himself, from the splendour of a post-war professorial chair in Harvard, assessed and constructed his cultural inheritance eloquently and carefully. “The idea was to mix up these things to see that there is no barrier between a painting and the other things of our environment... I consider beauty a basic requirement of life.” There was a tantalisingly short intervention from the quiet but crystal-clear voice of Josef Albers, who more or less summarised the whole history of the school in one well-turned sentence: “In Weimar it was a state institute, in Dessau municipal, and in Berlin we were a private institute.”

The film was book-ended with a telling episode about the political punk band Feine Sahne Fischfilet from the Rostock region in North-Eastern Germany. They had been booked to perform in the Bauhaus building in Dessau in November 2018. It became a big national story in Germany because neo-Nazis had threatened to demonstrate against the appearance, and the director of the foundation which runs the building, listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, backed by the cultural powers-that-be in Dessau (from Merkel’s party the CDU) uninvited the band. The actual result, incidentally, not mentioned in the documentary, was that the band achieved far bigger notoriety from the story: the promoter switched the venue to a brewery elsewhere in Dessau where they played to an audience about five times as large. This story gave the beginning and the end of the film a nicely edgy soundtrack, and was also a reminder of a consistent theme, that art and design can never be removed from the politics that surround them.

Add comment