Peer down the glassy dark and you’ll see them. White bubbles trapped in the frozen lake which appear to be rising to the surface. Look through the permafrost this way and you’re seeing into the past: as the ice melts, gas which was captured and stored tens of thousands of years ago when woolly mammoths and sabre-toothed cats stalked Alaska is released into the atmosphere. Each slick of melt water is another decade returning to the rivers. A scientist pokes a flare towards a hissing vent and the lake burps fire. It is methane, a gas with 21 times the smothering effect of carbon dioxide which is itself the main driver of climate change.

It’s a bitter irony that David Attenborough, who began his career flush with the ability to convey the wonders of the natural world, is now, at 92, warning of its imminent demise. In his latest programme, Climate Change: The Facts, devastating footage of last year’s climactic upheavals makes surreal viewing — typhoons, forest fires, storm surges, mirages sunrises.

A car drives along a spit of road - now a kind of bridge - through swathes of submerged land in Indiana. An iceberg calves and upends itself; runnels of water carve channels through a glacier. A forest floor in Australia is littered with mewling black lumps, bats killed by a heatwave with their offspring still alive and clinging to their corpses. Lined up in rows they look like bodies bagged after a massacre. A father and son drive through a forest fire, their journey and increasingly frightened interchanges captured by the dash cam; around them is hell. Families wade through thigh deep water submerging a city in Kerala, guided by ropes to which they cling against flood currents.

A car drives along a spit of road - now a kind of bridge - through swathes of submerged land in Indiana. An iceberg calves and upends itself; runnels of water carve channels through a glacier. A forest floor in Australia is littered with mewling black lumps, bats killed by a heatwave with their offspring still alive and clinging to their corpses. Lined up in rows they look like bodies bagged after a massacre. A father and son drive through a forest fire, their journey and increasingly frightened interchanges captured by the dash cam; around them is hell. Families wade through thigh deep water submerging a city in Kerala, guided by ropes to which they cling against flood currents.

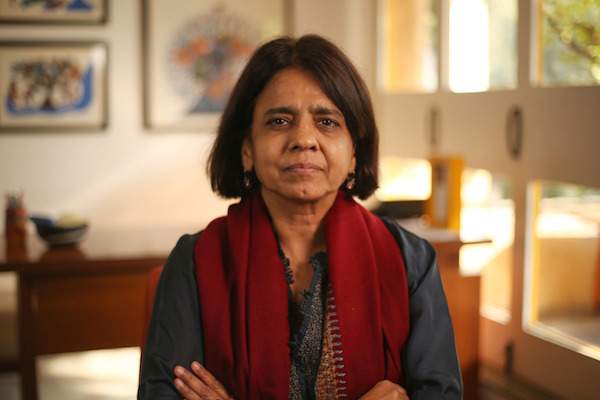

These images only show what has already happened. Interviews with professors (including Professor James Hansen, pictured below, who testified before American Congress on global warming in 1988), government officials, environmentalists, academic and field researchers, and industry spokespeople which drive and structure the programme articulate these changes and project them into the future.

Before humans began burning coal, atmospheric concentrations of CO2 stood at 280 parts per million; they now stand at over 400 parts per million. Around 8% of wildlife is estimated to be at threat of extinction. Sea levels have risen by about 20cm in the last 100 years and could rise by 80cm-1m by the end of the century, engulfing agrarian villages and urban metropolises alike and causing economic chaos. The first climate refugees in America are being relocated; Pacific Islanders' birthplaces will soon be lost to the waves. A third of the world’s coral has already bleached and died. Even the optimistic end of current models promise a ravaged and unfamiliar planet by the end of this century is predicted to be between 3-6˚C hotter.

A bleak picture emerges of the scale of the damage already wreaked and the urgency of the action required to slow — let alone pause — catastrophe. The targets set by the 2015 Paris Agreement (to keep global temperatures below +2˚C and as close to +1.5˚C as possible) require emissions to drop to net 0% by 2050. The last time the world had current levels of CO2 concentrated in the atmosphere was around 3 million years ago, when temperatures were 2-3˚C hotter than pre-industrial levels and sea levels significantly higher. The forebears of Homo Sapiens lived but the comparison shows just how fragile human life is: while Earth has survived radical climactic changes and regenerated following mass extinctions, it’s not the destruction of Earth that we are facing, it’s the destruction of our familiar, natural world and our uniquely rich human culture.

A bleak picture emerges of the scale of the damage already wreaked and the urgency of the action required to slow — let alone pause — catastrophe. The targets set by the 2015 Paris Agreement (to keep global temperatures below +2˚C and as close to +1.5˚C as possible) require emissions to drop to net 0% by 2050. The last time the world had current levels of CO2 concentrated in the atmosphere was around 3 million years ago, when temperatures were 2-3˚C hotter than pre-industrial levels and sea levels significantly higher. The forebears of Homo Sapiens lived but the comparison shows just how fragile human life is: while Earth has survived radical climactic changes and regenerated following mass extinctions, it’s not the destruction of Earth that we are facing, it’s the destruction of our familiar, natural world and our uniquely rich human culture.

This is a point the programme touches on, albeit lightly. Future climactic changes will precipitate political instability, social upheaval and the mass movement of people escaping drought, famine and flooding on a scale never before been seen. Whether human kind can survive this, let alone the vicissitudes of climate change, is a valid question. We may yet in more ways than one be the originators of our own demise.

Who knows if any or all of these will make a difference in time. The danger is of hitting a tipping point whereby an irreversible process is triggered and emissions spiral out of control. Back to those white bubbles. If the permafrost melts, the methane release will be one of those tipping points. Terminal. To look into the depths of the Alaskan permafrost is therefore also to scry the future. Fear it — this methane, that fire, could be what it holds.

Add comment