The eel is dying. Its body flits through a series of complicated knots which become increasingly grotesque torques. Immersed in a pool of brine — concentrated salt water five times denser than seawater — it is succumbing to toxic shock. As biomatter on the sea floor of the Gulf of Mexico decomposes, brine and methane are produced, and where these saline pockets collect, nothing grows. Dead creatures drop into it; live creatures that linger in it die. In this lifeless zone their bodies float preserved, a rich and dangerous larder for scavengers such as the giant mussels fringing its edges and the cutthroat eels which torpedo in and out of the deadly arena to snatch meals from the pickled corpses.

This death field is invisible and natural, apparent only through the warning implied by the barren seafloor. But for each of the seven episodes of BBC One's Blue Planet II, the whetted edge between life and death has been ever-present and razor sharp. The final episode of this spectacular series focusses on the ordinary interactions between humans and animals, both exemplary (the Trinidadians who now take great pains to preserve leatherback turtle nesting sites when previously turtle meat was a regular foodstuff) and disturbing (footage of a sperm whale swallowing a broken plastic bucket is devastating). Its conclusions: we humans are destroyers and custodians both of our oceans. Principled, impassioned people are working to safeguard disappearing species and precious environments, but we are all implicated, we are all responsible. Around 71 percent of the surface of the earth is covered by water, and metaphor is the means by which the series has rendered the utterly strange accessible: beneath the waves we have coral cities, algal prairies, seaweed forests, and submerged pick-up spots, populated by familial pods of cetaceans, interdependent communities of fish, lone predators, intrepid turtles, and randy cuttlefish. As with the stirring orchestration, zinged colour calibration and liberal foley these are artificial concepts which give shape to what might otherwise be mere spectacle. But the animal world has winners and losers and hierarchies to rival the human, so the daily argy-bargy of survival naturally breeds material dramatically primed for narrative. The skill of the series is in drawing fine distinctions between tussles of appetite by inflecting each vignette with humour, triumph, morality.

Around 71 percent of the surface of the earth is covered by water, and metaphor is the means by which the series has rendered the utterly strange accessible: beneath the waves we have coral cities, algal prairies, seaweed forests, and submerged pick-up spots, populated by familial pods of cetaceans, interdependent communities of fish, lone predators, intrepid turtles, and randy cuttlefish. As with the stirring orchestration, zinged colour calibration and liberal foley these are artificial concepts which give shape to what might otherwise be mere spectacle. But the animal world has winners and losers and hierarchies to rival the human, so the daily argy-bargy of survival naturally breeds material dramatically primed for narrative. The skill of the series is in drawing fine distinctions between tussles of appetite by inflecting each vignette with humour, triumph, morality.

And through these narratives we have seen genuine wonders: 60 metre-high kelp glades which absorb 35 times more CO2 than a rainforest, coral structures the size of a house built by thousands of generations of tiny hungry polyps, voracious 10-armed sea cucumbers, fleets of rays strobing in phosphorescing seas, skeletal fanged predators prowling depths light cannot penetrate, and orcas whipping through swirling veils of herring, herding shoals into balls before stunning them with mighty tail slaps.

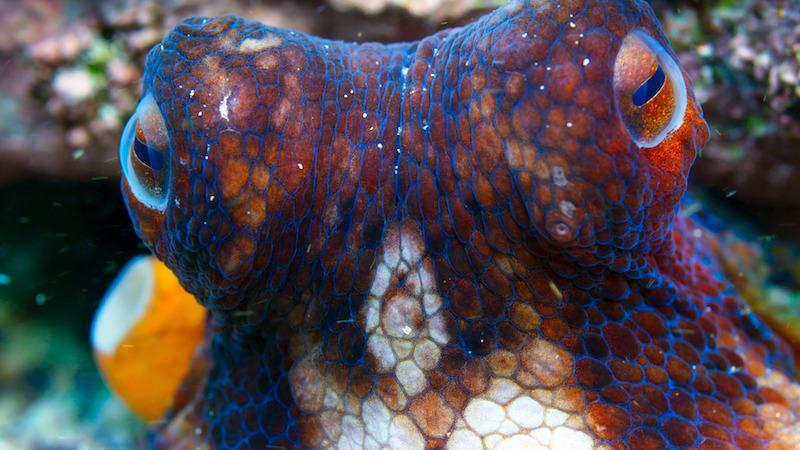

The strange landscapes and compulsive stories entice us to look closer. It is what scientists do every day, but mere audiences get the enhanced version: concentrated drama and high revelation which in turn can overthrow assumptions about unwarranted anthropomorphism. Take, for instance, the octopus, a creature of such alien intelligence its neurones are spread across its brain and body, meaning each arm can think. They exhibit curiosity and ingenuity – individual octopuses are commonly ascribed distinct personalities – and the one followed by the Blue Planet team which outwits the humbug-striped pyjama shark by armouring itself with shells is clearly fit for stardom. The ordinary texture of the lives of animals and sea creatures has been so long hidden that now, coming across tuskfish using stones to crack clams for their meat, albatrosses that mate for life, seals that collectively strategise to hunt down tuna, or clownfish that warn each other in pops and grumbles of approaching predators, we are overwhelmed by the complexity of animal behaviour, the intricacy of the natural world of which we are a tiny, but influential, part. Spectacle inspires awe; stories convey meaning. Whether or not the narrative drama of Blue Planet II is indigenous to the patiently accumulated footage is by-the-by: its meta-narrative is the health of our oceans. Every image, every word is geared to impress the urgency of this upon us. Just as fast as we are exploring the wonders of the oceans, so too are we realising the extent of our damage to it. Plastic particles have been found in the stomachs of the deepest of sea creatures, and every year eight million more tons of plastic finds its way into the oceans. Sea temperatures are rising, acidity is increasing, and drastic events like coral bleaching and the calving of a massive iceberg from the Larsen C ice shelf throw into relief the creeping dangers of climate change.

Spectacle inspires awe; stories convey meaning. Whether or not the narrative drama of Blue Planet II is indigenous to the patiently accumulated footage is by-the-by: its meta-narrative is the health of our oceans. Every image, every word is geared to impress the urgency of this upon us. Just as fast as we are exploring the wonders of the oceans, so too are we realising the extent of our damage to it. Plastic particles have been found in the stomachs of the deepest of sea creatures, and every year eight million more tons of plastic finds its way into the oceans. Sea temperatures are rising, acidity is increasing, and drastic events like coral bleaching and the calving of a massive iceberg from the Larsen C ice shelf throw into relief the creeping dangers of climate change.

Attenborough may guide us through this rich world of wondrous variety, but we are each protagonists and players in this story.

Add comment