This emotive, even emotional half-hour programme focussed on a famous children’s book, The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby, and its author, one of those totally astonishing Victorian polymaths, the Reverend Charles Kingsley (1819-1875). It was a surprising example of the ways in which words can change the world.

With immaculate side whiskers and upright appearance, Kingsley, a devoted pater familias, could have seemed simply a confident and conventional Victorian. In fact he was a fascinating proponent of evolution, a Christian socialist, a controversialist, deeply disturbed by Catholicism – he had a famous interchange with Cardinal Newman – and an ardent pipe smoker. Hardly perfect, though: he was also horribly prejudiced against the Irish. He was also an historian, a poet, and a vicar for over 30 years in Eversley, Hampshire, a village near one of the most famous fishing rivers in England, the Blackwater. He wrote scores of books, articles and pamphlets, campaigned against social injustice, and was a gifted amateur naturalist: Glaucus was his handbook to the flora and fauna of rockpools.

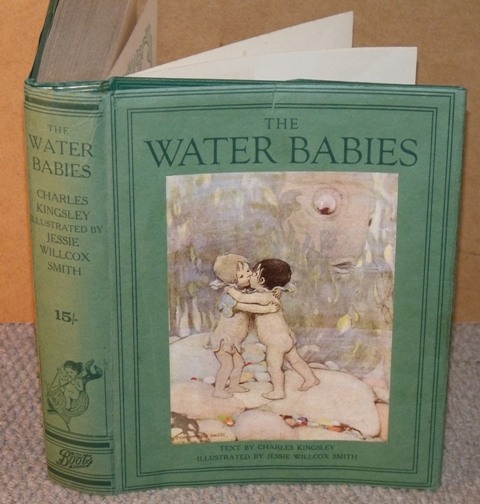

Our guide to Kingsley’s world was himself a clergyman, musician-turned-Reverend Richard Coles. So we visited Kingsley’s rectory, and Westminster Abbey too. The Water-Babies was described as an underwater Pilgrim’s Progress, and as not only a children’s fantasy but a political tract, scientific satire and Christian parable. An awful lot for a fairy tale to bear, but Water-Babies did so with beguiling grace (illustration for The Water-Babies by Jessie Willcox Smith, right).

Our guide to Kingsley’s world was himself a clergyman, musician-turned-Reverend Richard Coles. So we visited Kingsley’s rectory, and Westminster Abbey too. The Water-Babies was described as an underwater Pilgrim’s Progress, and as not only a children’s fantasy but a political tract, scientific satire and Christian parable. An awful lot for a fairy tale to bear, but Water-Babies did so with beguiling grace (illustration for The Water-Babies by Jessie Willcox Smith, right).

Kingsley had already written a children’s book for each of his three daughters, and his beloved wife Fanny reminded him that he had yet to write a tale for his fourth child, his son Grenville Arthur. The Water-Babies is indeed a rather extraordinary meditation on the ideas and ideals of Darwin, Kingsley’s friend and correspondent. Kingsley saw no conflict between biology and belief. The hero Tom is a child chimney sweep, who falls down a chimney into the bedroom of a little rich girl, Ellie; Tom does not recognise himself as the little black boy with white teeth that he sees in the mirror but it is he, covered with soot. Somehow he and Ellie tumble into the nearby river, and Tom is transformed into a four-inch water creature, miraculously cleansed; Kingsley was a passionate believer in the virtue of cleanliness.

Tom cavorts safely among a myriad of aquatic life, real and imaginary, and cue gorgeous pictures of rippling water, fish, strange creatures in shells, and jellyfish. Not only that – meeting the drowned Mr Grimes, his abusive master, now condemned to purgatory and stuffed into a chimney pot, Tom releases Mr Grimes from his eternal bondage; Tom is redeemed by his forgiveness of his oppressor. Kingsley ended his absorbing narrative with this admonition: “You are not to believe a word of it, even if it is true.”

Once incredibly widely read and famous, The Water-Babies has now almost faded from the pantheon. But it was not only incredibly popular in its time and beyond, it influenced the political processes towards social reform. The Water-Babies was as much polemic as fairy tale. A year or so after its publication in 1862, Parliament passed laws prohibiting anyone under 21 from cleaning chimneys: the miserable lives of multitudes of malnourished child workers, dying early of abuse, cancer, lung disease and accidents, had long been a national scandal.

Once incredibly widely read and famous, The Water-Babies has now almost faded from the pantheon. But it was not only incredibly popular in its time and beyond, it influenced the political processes towards social reform. The Water-Babies was as much polemic as fairy tale. A year or so after its publication in 1862, Parliament passed laws prohibiting anyone under 21 from cleaning chimneys: the miserable lives of multitudes of malnourished child workers, dying early of abuse, cancer, lung disease and accidents, had long been a national scandal.

This tautly made programme, stuffed with facts, ravishing underwater photography and glimpses of the Hampshire countryside, was accompanied for once by music that enhanced the magical mood of the novel and its captivating aquatic world.

Add comment