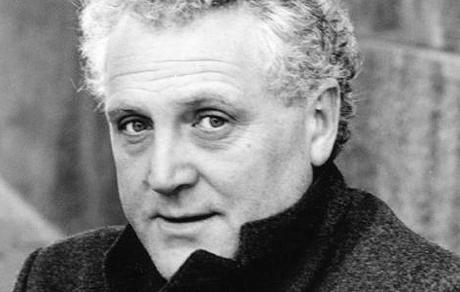

“There is a sense I very much get about this place. Italians know what life is for and they know it won’t last very long. And so they take advantage. I like that. Particularly at my age.” The last of several times I interviewed the British crime writer Michael Dibdin (1947-2007) was four years before his death. It was a freezing February morning in Bologna, where he was researching the 10th and (it turned out) penultimate book in the Aurelio Zen series. The interview was at 9am. In the fug of a crowded bar, Dibdin soaked up several espressi and a warming tot of grappa.

Having concluded our business we shouldered our way into the grid of narrow alleys just off the Piazza Maggiore, the cold air aromatic with the intoxicating whiff of grana padano and prosciutto crudo. Dibdin needed to buy supplies to take back to the apartment he was staying in. Shopping for food in streets which are, in effect, the gastronomic epicentre of all Italy, here was Dibdin’s chance to play the Italian epicure. Instead he penitentially limited himself to a box of half a dozen eggs.

At the time it struck me as uncharacteristic of a man of unstinting appetite who, every time I met him, seemed that little bit heftier. On reflection, his box of eggs was entirely in tune with the spirit of Zen and the series which starred him. Migrating in each novel to a different region in Italy, Dibdin took care to skirt around the sensual side of Italian life beloved of Tuscanophile holidaymakers. Zen’s longest and in fact only stop in Florence is a pre-dawn train change. “What are you going to say about Florence?” he once said to me. “It’s been done to death.”

The spectral Zen, a shadowy detective answerable directly to the conniving Interior Ministry in Rome, is for my money the most fascinating of Euro-cops solving crime in print. Fortified by Venetian cunning and unfazed by ethical compromise, he weaves a guileful path through a moral maze of easy corruption and institutionalised patronage, brusquely cutting corners, blithely breaking rules, opening cans of worms, but in the end fatalistically accepting that it is never quite possible to penetrate to the heart of the eternal labyrinth that is modern, and indeed ancient, Italy.

The spectral Zen, a shadowy detective answerable directly to the conniving Interior Ministry in Rome, is for my money the most fascinating of Euro-cops solving crime in print. Fortified by Venetian cunning and unfazed by ethical compromise, he weaves a guileful path through a moral maze of easy corruption and institutionalised patronage, brusquely cutting corners, blithely breaking rules, opening cans of worms, but in the end fatalistically accepting that it is never quite possible to penetrate to the heart of the eternal labyrinth that is modern, and indeed ancient, Italy.

Zen and his creator are risen again in the form of a new three-part television adaptation. It has been one of the slowest burns in detective history. The BBC had the option when I first met Dibdin in 1995. Julian Mitchell was working on a script which never came to pass. Now the second, third and fourth books – Vendetta, Cabal and Dead Lagoon – find the lugubrious detective taking the form of Rufus Sewell (pictured above).

Sewell and Zen may not seem an especially apt match, but for anyone who has a specific vision of how Zen should look, Dibdin would have had the answer. “I don’t think I know that much about Zen really,” he told me in 2003. Nor had he ever quite worked out who Zen’s fans really were. In A Long Finish, the sixth Zen, he indulged them with descriptions of truffle-hunting mores, of viticultural custom and thick autumnal fog blanketing hill-crest villages in Piedmont. Sales duly tripled.

In the follow-up, as a sort of corrective, Dibdin decided that it was time for Zen to take on the Sicilian Mafia. If you didn’t read the final paragraph of Blood Rain carefully enough, the detective appeared to come to an explosive end. “I discovered that almost everyone thought he was dead,” Dibdin later told me. “On some level it slightly got up my nose. I was getting contact from people who were saying, ‘How dare you?’ I thought, wait a minute, I invented this character.”

In the follow-up, as a sort of corrective, Dibdin decided that it was time for Zen to take on the Sicilian Mafia. If you didn’t read the final paragraph of Blood Rain carefully enough, the detective appeared to come to an explosive end. “I discovered that almost everyone thought he was dead,” Dibdin later told me. “On some level it slightly got up my nose. I was getting contact from people who were saying, ‘How dare you?’ I thought, wait a minute, I invented this character.”

Zen’s 11th case, End Games, inadvertently answered a question that Dibdin always fretted about: what is the appropriate length for a crime series? “Some say seven, some 10,” he said when he had written the fifth, Cosi fan tutti, set in Naples. “I think if it's a serious series, if you're really trying to write books rather than churning out a formula, then 10 is there or thereabouts.” In this conflation of our various conversations, Dibdin talks about the genesis of Zen, the business of coming up with fresh plots marinaded in contemporary Italy, and writing in English about Italians.

JASPER REES: Why did you first come to Italy?

MICHAEL DIBDIN: I had published The Last Sherlock Holmes Story. It had sold 800 copies. I couldn't think of any way to follow this up. I got working with the Vietnamese boat people. They had a place out at Syon Park where they were bringing members of the family in. I did a bit of work with them. One of the people running the project said, “Why don't you take a qualification in TEFL and then you can travel anywhere and see what you want to do?” They then offered me various jobs. The first was in Ankara. Then one in Libya. And then quite unexpectedly a job came up in Perugia. Off I went and I was there for five years.

And Zen was born?

And Zen was born?

He was really secondary to the project of the first book [Ratking], which was to write a book about Perugia, where I lived for five years, and about Italy in general. I needed an outsider who would come into this rather small, closed, introverted society and try and crack its codes and tap into its networks and have to insinuate himself in from the outside in the face of a certain amount of suspicion as a policeman and as an unknown quantity. At that point he was an enabling character in a one-off book. Then Ratking won the Gold Dagger award and people kept saying, “When's the next Zen book coming along?” At that point I was no longer living in Italy and I realised that I would very much like to go on writing about it.

Did you ever consider writing about Florence?

I’ve thought about that one but the beach scene in And Then You Die is probably as close as I want to come to Tuscany. It really has been done to death, particularly by foreign writers. And I don’t mean done badly. But it’s pretty well-trodden territory. What are you going to say about Florence? The only place I’ve done which comes in that league is Venice in Dead Lagoon and I really knocked myself out to not do Venice in the way it has been done. But if you have someone come from Venice there's only a certain amount of time you can go on dodging writing a book about it. I was slightly apprehensive of adding another bad book about Venice to the already infinite list of bad books about Venice. With Venice you're taking on Mann, Proust, James, a lot of big names. Who was the man who said Venice is a city about which there is famously nothing more to be said? And that was in 1890 or something. I did think you have to have a certain amount of chutzpah to take this one on.

This is what pisses me off about publishers. Ever since Ratking, what I did not want to do was write a book using my Italian experiences as a kind of spray-on local colour to glam up something which wouldn't have been terribly interesting without it. The police in Italy are in an interesting position because they are the hinge between the public and the private. They have to investigate private stuff - there's a body on the floor - but they are representatives of the state, and of course this is a very tortuous and devious relationship here. I didn't want to have “the contessa looked beautiful in blue chiffon tonight” scenes.

You succumbed to the temptation of beautifying Italy a bit in A Long Finish. Why the wine trade?

You succumbed to the temptation of beautifying Italy a bit in A Long Finish. Why the wine trade?

When I lived here it seemed to me that it was one of the most characteristic differences from region to region and one would be a fool not to take advantage of that. The problem with a crime series is there's always a risk that it will become repetitive. That you will have a familiar character with a familiar place. Piedmont is a very charming bit of Italy and indeed relatively crime-free. The challenge here was to write about what is essentially the Italian equivalent of the Cotswolds and write a crime novel about it. It's difficult to avoid the charm because it oozes charm. Because Italy is associated with wine in a lot of people's minds. Italian wine was regarded as cheap and cheerful. In the last 25 years the situation has changed dramatically, particularly in Piedmont. Any place that money is being generated is automatically of interest and potentially a scene for a crime novel. There's something very English about the countryside. It's what the English countryside could look like if it tried a bit harder.

Does Zen work as a passport when trying to get into police stations? How do you approach, say, the questura in Naples for Cosi Fan Tutti?

You need a connection. I know someone who works at the consulate in Naples and he obviously has a lot of dealings with the police when British nationals get into trouble and whatever, so he knows all these people and he says he can get me in. But it's not easy because apart from anything else the Italian police are still basically governed by laws passed by Mussolini in terms of their organisation and above all the degree of secrecy which surrounds the organisation. So in a way it's probably easier to get into something like the KGB than the Italian police. And there are no books about them. You can't do research in the way that you could over here. If you go down to the local library here, there's a whole shelf of books written by investigative reporters who've spent six months with the crime squad in Liverpool or something. No one gets to do that in Italy. Or at least I don't know of anyone who has. And in fact when you do meet these policemen having been raccommandato the first thing you make clear is that you're writing fiction and you're not writing non-fiction, because if they think you're going to write a non-fiction exposé of what goes on then you won't get a damn thing out of them. They're very suspicious. For two reasons, the principal one being that they could get into enormous trouble obviously.

You need a connection. I know someone who works at the consulate in Naples and he obviously has a lot of dealings with the police when British nationals get into trouble and whatever, so he knows all these people and he says he can get me in. But it's not easy because apart from anything else the Italian police are still basically governed by laws passed by Mussolini in terms of their organisation and above all the degree of secrecy which surrounds the organisation. So in a way it's probably easier to get into something like the KGB than the Italian police. And there are no books about them. You can't do research in the way that you could over here. If you go down to the local library here, there's a whole shelf of books written by investigative reporters who've spent six months with the crime squad in Liverpool or something. No one gets to do that in Italy. Or at least I don't know of anyone who has. And in fact when you do meet these policemen having been raccommandato the first thing you make clear is that you're writing fiction and you're not writing non-fiction, because if they think you're going to write a non-fiction exposé of what goes on then you won't get a damn thing out of them. They're very suspicious. For two reasons, the principal one being that they could get into enormous trouble obviously.

Have you got into the questura in every town?

Frankly, if you’ve seen one questura you’ve seen them all. The police are a completely centralised authority. They look exactly the same from one end of the country to the other. It’s just like railway stations.

To what extent is your highly entertaining portrait of the rivalry between Defence and Interior Ministries accurate?

The carabinieri and the polizia di stato? It wouldn’t stretch any Italian’s imagination for a second. It’s well known that there are two separate ministries. Each ministry has a separate minister; traditionally, although this has not always been the case, they will be from different parties. One will get the interior and the other party will get the defence. And of course they’ll be at each other’s throats. Plus one only has to look at the situation in Britain. MI5 and MI6 and Special Branch, they are all fighting over territory. No one likes anyone muscling in on their turf. There is intense rivalry. That’s why Mussolini created the polizia di stato in the first place, because he didn’t trust the carabinieri, who were originally founded by Victor Emmanuele. They were always vaguely regarded, because they were part of the army, as aristocratic, old guard, and Mussolini, being a man of the people in his way, didn’t trust them. So he created the polizia di stato as a counterbalance. After the war no attempt was made to reform this, so it’s a checks-and-balances kind of thing.

Is there a sense in which Zen is doubly fictional, because there is no such thing as an unbent cop in Italy?

I don't know. It's difficult to know statistically. I think there are unbent cops in Italy. It depends what you mean by bent.

Tied up with politics.

Tied up with politics.

Well yes, but then Zen is tied up with politics in one way and another. He's subject to pressures. He's also having to ask himself not how do I solve this case but do important people who can have an effect on my career actually want this case solved, and what sort of solution do they want? Bent's not a bad word if what you mean by that is you have to be flexible and take a crooked line - because I don't think there are any straight roads in Italy, morally or in terms of a career in investigation: you don't go straight from A to B in the way in which someone like Adam Dalgleish or Wexford does. You have to go in a roundabout way so in some sense you have to be slightly distorted yourself or you become distorted just out of the pressures of the job. I'm quite prepared to believe that there are people who go into the police force in Italy as keen young hungry wolves but I would think that four or five years' experience would soon knock that out of them.

Was it luck or nous that Zen came along at the right time and turned into a Zeitgeist cop just when the whole thing blew up?

He's been around since 1984. I think that was just luck. Dead Lagoon happened to coincide with this change, although "change" here has to be in inverted commas. I'm sure you know the Italian expression, "Everything has changed so that nothing will change." That’s Lampedusa’s line in The Leopard. It’s a classic Italian fatalistic cynical expression of the truth.

There are plenty of Italians who believe by now that nothing really has changed. It's revolution in the original sense of the word, which is a wheel that goes round and comes back to the same place. It may well be that kind of revolution in the end. All these currents were always there in Italy. One always knew that the old guard, Andreotti and Craxi and all the rest of them, were up to their necks in it. As someone says in one of Chandler's novels, referring to another character who's a multimillionaire, "No one gets that rich legally." By the same token, no one stays in power the way those people stayed in power in Italy without being tainted in one way or another, whether it's in massive kickbacks or connections in organised crime or whatever. So one always knew that was the case. What I think no one guessed is that the end would come so soon and so quickly. I remember an Italian friend saying that the only way Andreotti would ever leave power would be horizontally. I went at Easter and came down with flu and had to spend most of my time watching television and on the same news broadcast I saw Renato Curcio, who was the head of the Red Brigade, being released from prison having served his 15 years or whatever it was. The next item was Andreotti going to the senate to defend himself against charges laid by magistrates in Palermo, that he'd had General della Chiesa, who was the prefect of Palermo and the man who incidentally smashed the Red Brigades and Curcio, contract killed by the Mafia because Della Chiesa knew too much about Andreotti's part in the death of Aldo Moro.

There are plenty of Italians who believe by now that nothing really has changed. It's revolution in the original sense of the word, which is a wheel that goes round and comes back to the same place. It may well be that kind of revolution in the end. All these currents were always there in Italy. One always knew that the old guard, Andreotti and Craxi and all the rest of them, were up to their necks in it. As someone says in one of Chandler's novels, referring to another character who's a multimillionaire, "No one gets that rich legally." By the same token, no one stays in power the way those people stayed in power in Italy without being tainted in one way or another, whether it's in massive kickbacks or connections in organised crime or whatever. So one always knew that was the case. What I think no one guessed is that the end would come so soon and so quickly. I remember an Italian friend saying that the only way Andreotti would ever leave power would be horizontally. I went at Easter and came down with flu and had to spend most of my time watching television and on the same news broadcast I saw Renato Curcio, who was the head of the Red Brigade, being released from prison having served his 15 years or whatever it was. The next item was Andreotti going to the senate to defend himself against charges laid by magistrates in Palermo, that he'd had General della Chiesa, who was the prefect of Palermo and the man who incidentally smashed the Red Brigades and Curcio, contract killed by the Mafia because Della Chiesa knew too much about Andreotti's part in the death of Aldo Moro.

It's a ratking.

It is, but it's a challenge, because if you put that in a novel people would say you are exaggerating.

They'd also lose you, because it's too complicated.

It is, but Italians love the complications of conspiracy theories.

Is it odd seeing your Zen novels in Italian? Do they work in Italian?

I must say I'm not terribly happy with the standard of translation. They're published by Mondadori, who are the biggest publisher in Italy. The problem is really they're translated them quite quickly and obviously the translations are correct but there isn't a lot of life in them, particularly in the way the dialogue is translated; maybe they don't grasp the different registers I'm using in English but there speaking in a rather stiff Radio 4 afternoon-theatre way in Italian, whereas that's not in fact how cops would talk to each other. For instance, they would talk in a much slangier way.

Was the dialogue written with Italian speech rhythms in mind?

I tried to hear it in Italian first. Interestingly it quite often comes out sounding more like American than British English. Americans tend to be more direct, and Italian sounds more direct, although of course what you can't translate is the thing which mitigates the directness, which is the use of a polite form of the verb. Whereas if we go to the Coach and Horses we would say something along the lines of, "Could I have a pint of beer please?" What we would not say is what the Italians and Americans would say, which is, "Gimme a beer.” It's just inconceivable. But of course the Italians will say that with the polite form of the verb, on the whole, unless they know the barman. But the form is exactly the same. Dammi una birra.

The dialogue is always slightly... I wouldn’t say problematic but you do have to think about what you’re doing. Obviously I can’t write it in Italian. There are certain ground rules which have by now for me become completely internalised so I don’t have to think about it any more. You can’t use any obvious or extreme British or American idioms unless it’s a case where the Italians would be using an extreme idiom. In which case you simply have to go for something. You can’t have people talking like robots. Most of the time Italians do speak more or less correct and coherent Italian, as opposed to when they are speaking in dialect. That’s not too difficult to do. You don’t want people saying, "Well, I really should have gone because I couldn’t be arsed," because that’s not going to work.

Did you know Italian before you went to teach in Perugia?

Not really, no. I did a short course somewhere, but when I arrived I couldn't say very much.

I read that you took your observation of police practices from your experience of machinations and politicking within the teaching profession.

I read that you took your observation of police practices from your experience of machinations and politicking within the teaching profession.

Within the university. The universities in Italy are a branch of the state. They're funded by the state and also the basic bureaucracy is entirely state-run. There doesn't seem to be very much in the way of autonomy. So essentially they're part of the basic bureaucratic apparatus, like the post office or the police service. Just watching the way things got done, or failed to get done, in the department that I was working for really gave me some insights into the way that things must happen in other aspects of the state organisation. There are countless examples of this. My favourite one, which I put into Ratking, involved the doormen, the portieri of the istituto where I taught, which was a lovely old medieval building in the centre of Perugia, and had been lovingly restored. They'd obviously spent an absolute fortune on this, and they had high-quality equipment and the last word in language labs and everything. And the building was run by these two portieri, who as I discovered later were both political appointees. One was an old Stalinist, and the other was an old Fascist. They were both equally disagreeable, equally unhelpful, and they just squatted there in their little cubicle by the front door all day long. The point was these people would not be fired.

Is Zen a passport for you or is he unknown in Italy?

No, all the books are published in Italy. They're interested that someone is writing about Italy in what for them is a very normal way, in that it's not making a big deal out of the kind of things that foreigners quite often do make a big deal out of. The exotic tourist-attraction stuff but also with some understanding of the way things actually are. If you're there for any period of time, more than, say, a year or two, and you're not completely uninterested or out of it - there are people, Italy for them is the Renaissance and beautiful churches and nice food, even though they're maybe expatriates who've lived there forever - but if you read the papers and have Italian friends and talk to them about what's happening you quite quickly realise that Italy is a complex society which functions just as well as our own functions, but it functions in a different way, and that a lot of people's received ideas about the place are actually completely wrong. Like the idea that Italians are all happy-go-lucky, light-hearted, rather superficial people who dance and sing their way through life with a smile on their lips.

Are there areas of overlap between you and Zen? He's a grouchy maverick.

Are there areas of overlap between you and Zen? He's a grouchy maverick.

He's partly based on Italians I know, partly on a certain perception I have of what Italian bureaucrats are like, and partly on me. In the Catholic parts of Europe there is a kind of Mediterranean fatalism about what is achievable and what isn't. Even fix a few small things here and there. But anyone who thinks they can go out and change the world tends to become canonised 300 years later, but you wouldn't want to share an elevator with them.

Zen has a younger girlfriend or two (pictured above: Caterina Murano with Rufus Sewell). Is that a fantasy?

Oh that's not nearly as much of a fantasy in Italy as you might suppose. I was down in Sicily recently researching, and I was getting looks in the street which I have not got for 15 years. To an extent which is unthinkable now in England or America, women in Italy are not really interested in how old you are or what you look like or how thick your waist is. They're interested in a sense of power and confidence and if you radiate that you can pull the birds with no trouble at all.

How much time do you spend on the ground in Italy researching? Let’s take the ninth Zen book Medusa, which is unusual in that it’s the most geographically diffuse of the series.

How much time do you spend on the ground in Italy researching? Let’s take the ninth Zen book Medusa, which is unusual in that it’s the most geographically diffuse of the series.

I was in the North of Italy, in the Valpolicella area for an abortive project on a wine book commissioned by an American publisher. I discovered there was no book there. It was the old “I was misinformed line” from Casablanca. I was left twiddling my thumbs and went up into the Dolomites which I hadn’t been to before and discovered this system of military tunnels built by both sides in the First World War. They were just such an amazing thing, very, very high up, just the idea of even building them, never mind living in them for years, never mind under fire. It was like trench warfare 10,000 feet up. I just thought, I’ve got to do something with this. These tunnel systems have only been partially restored. I just thought what if a body turned up there. It would be an interesting place to find a corpse.

I spent most of my time on the ground researching that area because that wasn’t something that I knew terribly well. I went back to Rome to do a few specific areas. I want to make the distinction between pre-research and post-research. I remember Graham Swift once saying a lovely line when someone asked him, “How much research do you do?” He said something like, “Well, I basically write the novel first and do the research afterwards.” Which I think is fair enough.

I tend to do it both ways. I really come with no preconceptions at all, no specific questions. If I wanted to know how high the twin towers [in Bologna] are, you can find that out in 10 seconds from a guidebook or the internet. It’s just about steeping myself in the place and waiting for stuff to happen. Then when you’ve written the book you realise there are specific things that you need to know more about. In Medusa there is the hanging garden in Rome where Zen meets his boss. I’d been there several times years ago and I had a vague memory of it but I needed something more specific so I went back there. And also a clearer idea of what it’s like now.

I tend to do it both ways. I really come with no preconceptions at all, no specific questions. If I wanted to know how high the twin towers [in Bologna] are, you can find that out in 10 seconds from a guidebook or the internet. It’s just about steeping myself in the place and waiting for stuff to happen. Then when you’ve written the book you realise there are specific things that you need to know more about. In Medusa there is the hanging garden in Rome where Zen meets his boss. I’d been there several times years ago and I had a vague memory of it but I needed something more specific so I went back there. And also a clearer idea of what it’s like now.

Once you know where you are in Italy, how do you establish the plot you are going to tell?

It’s all very tentative. It tends to be feeling my way. I tend to have an idea of how it starts. Sometimes also of how it ends, but not always by any means. I do tend to write my books sequentially. But I write a lot of different drafts. What I try to do as soon as possible is get a first draft in shape. That may be originally in the form of storyboards. Sometimes bits of the scene will come to you and you think, all right I can do that right now. And there are others which don’t come to you but you know have to be there so you simply do a two-line thing in the outline, which says, "Zen goes to X, meets Y and Z happens." This is all just blocking in. The important thing for me is to get the first draft finished and a sense of narrative flow. It takes a long time. Much, much longer than I would like. I would say roughly on average three to four months. It’s horrible. I always feel it’s not going to work. The point is not that you’re only as good as your last book. The real problem is you’re only as good as your next book. The last book just sits there like the battleship at anchor in the bay. I think, God almighty, did I do that? When you are doing the first draft you think it might fall apart at any moment. For me the real enjoyable work starts with the rewriting. Once you’ve got something you can then look at it and say, “No, that won’t do.”

Although your ambition was to write about contemporary Italy, one of the seductions of the series is the irreducible glamour of Italy.

There is a sense I very much get about this place: Italians know what life is for and they know it won’t last very long. And so they take advantage. I like that.

Is Zen like that?

I think he is actually, on some level. I don’t really know that much about Zen, to tell you the truth. I know what he’s not like. But I don’t really care to know. I know that his mind sometimes works excellently and sometimes hardly works at all. He is obviously not dazzled by Italy the way that people coming here are but I think Italians are nevertheless, and a lot of Italians have said this to me – people who have spent long periods abroad – and they all say, “Yes, yes, I can live perfectly well in those places, but at a certain point it all feels a bit thin.” And I think, yeah, I know exactly what you mean. They can cope with the language and go about their work. But ci manca qualcosa, as the Italians say. There’s something missing and eventually they have to come back to get it. It’s that thing that’s missing of them which is per contra the plus for us. And we think, God, it’s amazing.

Do you ever feel pressure from readers? He’s never been abroad apart from, oddly, to Malta and in an unscheduled flight stopover in Reykyavik in And Then You Die.

I’m constantly being pestered by foreign readers, Belgians and Australians and New Yorkers and so on, who say, “We have a big Italian immigrant population here - why don’t you have Zen come to Sydney or New York or Brussels?” And one smiles politely and all the rest of it but frankly I can’t see that one working. But nevertheless I thought, there seems to be this pressure to send Zen abroad so I thought, given that And Then You Die is a pretty wacky book anyway... In the whole book he’s nowhere in particular, there’s the beach but it could be any beach, he’s betwixt and between and it doesn’t come any more betwixt and between than Iceland, I can tell you. But the actual idea of Iceland I got from a BA steward on one of the flights from Seattle. I was chatting to him during a sleepless interlude in the middle of the night and he was telling me about this flight he was on which was diverted in the mid-Atlantic to Iceland because the toilets got bunged up.

I’m constantly being pestered by foreign readers, Belgians and Australians and New Yorkers and so on, who say, “We have a big Italian immigrant population here - why don’t you have Zen come to Sydney or New York or Brussels?” And one smiles politely and all the rest of it but frankly I can’t see that one working. But nevertheless I thought, there seems to be this pressure to send Zen abroad so I thought, given that And Then You Die is a pretty wacky book anyway... In the whole book he’s nowhere in particular, there’s the beach but it could be any beach, he’s betwixt and between and it doesn’t come any more betwixt and between than Iceland, I can tell you. But the actual idea of Iceland I got from a BA steward on one of the flights from Seattle. I was chatting to him during a sleepless interlude in the middle of the night and he was telling me about this flight he was on which was diverted in the mid-Atlantic to Iceland because the toilets got bunged up.

The only time I really felt any pressure from readers was after Blood Rainwhen I discovered that almost everyone thought he was dead. I thought it was a stunt. Or if you want to dress this one up, it was an homage to the cliff-hanger ending. But it never occurred to me for a moment that he was dead. If you read it carefully... but of course no one ever does. I just got it wrong.

Did it give you an insight into who’s reading you?

Did it give you an insight into who’s reading you?

Not really who is reading me, no. On some level it slightly got up my nose. I was getting letters and phone calls and emails and also personal contact from book events who were saying, “How dare you?” I thought, wait a minute, I invented this character. If I want to get his body pierced and go out cruising the streets in a leather jacket with his bitch on a leash I can do that too. But when you create a character and people get attached to him they feel they own him. That’s good obviously because they were engaged. But I obviously just got that one wrong.

Do you have a sense of who you are writing for?

No, not at all. I really don’t. I mean except in a very general sense. I suppose I feel I’m writing for people who enjoy a good story, who are reasonably literate, who are interested in human nature, moral dilemmas of one kind or another, Italy. And can read words longer than one syllable. I sometimes feel there are fewer and fewer of these people around.

How many Zens would you do?

The received wisdom within the community is that you can’t go on forever, but precise estimations of what forever means vary enormously. Take Elmore Leonard. John Mortimer said to him, “Why don’t you do a series?” And he said, in his inimitable accent, “Well, I am doing a series. I’ve always done a series. It’s just that every one of the books in the series has different character names.” That’s just about dead on. Every one is the same basic structure and the same characters. I don’t know the answer. All I can tell you is I am an intensely lazy and self-critical guy so you put the two of those together. If there comes a point where the idea of writing about Aurelio again just elicits a huge yawn and sense of disgust I (a) won’t be able to do it and (b) won’t want to do it. Another question is how old is he? The answer is he is roughly as old as I feel I am.

Do you sense that you will be read for long?

Do you sense that you will be read for long?

I really don’t have a clue. It would be nice to feel that there was something there which people might want to read. I can tell you one thing. I really mean this. I don’t have any illusions about how good I am or how good I’m not. I think I’ve got a pretty exact idea of exactly how good I am.

How good are you?

Exactly as good as I think I am. But I’ll tell you this. There is nothing I’ve written, there isn’t a single phrase or line, which I’m ashamed of. And that is a great comfort to me in my old age. I don’t feel there is anything sleazy in the books. I don’t think there’s anything cheap. When I reread them I don’t think, eurgh, ick. I’ve never sold out because I thought it would increase sales or get me a readership. I’ve just done what I’ve done. If people like it, that’s great. If they go on liking it after I’m dead, that’d be nice too. But I’ve done what I can.

AURELIO ZEN'S TOUR OF ITALY

Ratking (1988) - set in Perugia

- Vendetta (1990) - Sardinia

- Cabal (1992) - the Vatican

- Dead Lagoon (1994) - Venice

- Cosi Fan Tutti (1996) - Naples

- A Long Finish (1998) - Venice

- Blood Rain (1999) - Sicily

- And Then You Die (2002) - Tuscan coast

- Medusa (2003) - Dolomites

- Back to Bologna (2005) - Bologna

- End Games (2007) - Calabria

- Vendetta is on BBC One at 9pm on Sunday 2 January, followed by Cabal on 9 January and Dead Lagoon on 16 January

Add comment