Can you make modern poetry come to life on a TV screen? The BBC has had two stabs recently at answering this question, as part of the centennary celebrations for TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, seen by many as the greatest poem of the 20th century. One programme works significantly better than the other.

For her 80-minute documentary TS Eliot: Into The Waste Land (BBC Two, ★★★★), director Susanna White was significantly aided by the “buried treasure” element in the story of this famously elusive poem, long laboured over by critics and students. Sitting like a ticking time bomb in Princeton’s archives was a cache of letters deposited there in 1970: the correspondence from Eliot’s long relationship with an American woman, Emily Hale (he had had all her letters to him burnt).

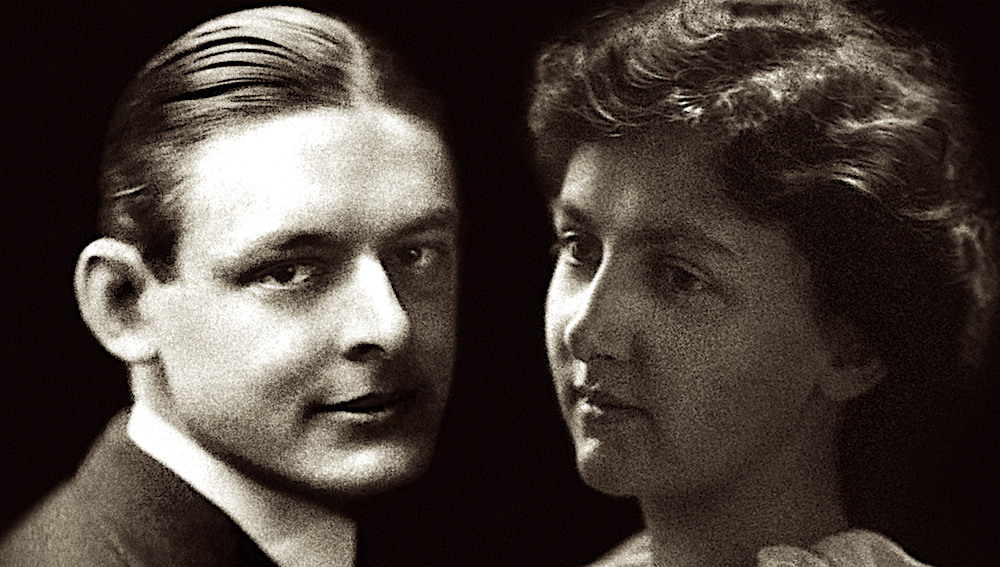

Eliot’s biographer, Lyndall Gordon, had long suspected Hale was the “hyacinth girl” in a line he had cut from an early draft of The Waste Land but later reinstated. The St Louis-born Eliot abandoned Hale and went to England in 1914, where he soon married Vivien Haigh-Wood. When the cache was opened in 2020, Gordon was proved right, though Eliot’s letters also turned out to be boobytrapped, warning the finders not to believe he ever loved Hale: “She would have killed the poet in me.” (Pictured below, Eliot with Hale) These revelations won’t be hot headlines for Eliot obsessives, but the rest of us can be very pleasantly entertained by this literary treasure hunt, which White handled sensitively and illuminatingly, despite the lack of visual materials at her disposal. The same few photos of Eliot with his St Louis family and with the exotic Vivien pop up, given artificial motion by a water effect that rippled across them. Elsewhere, White filled in the visual gaps with footage of commuters walking across London Bridge, or of blocks of flats like the one the Eliots lived in and spied on their neighbours from. In the chess section of the poem, we zeroed in on a delicate, intricately tooled chess set, like a little Renaissance cityscape. For the hyacinth girl passage, we saw a montage of a young woman in an Eden-like sunny garden.

These revelations won’t be hot headlines for Eliot obsessives, but the rest of us can be very pleasantly entertained by this literary treasure hunt, which White handled sensitively and illuminatingly, despite the lack of visual materials at her disposal. The same few photos of Eliot with his St Louis family and with the exotic Vivien pop up, given artificial motion by a water effect that rippled across them. Elsewhere, White filled in the visual gaps with footage of commuters walking across London Bridge, or of blocks of flats like the one the Eliots lived in and spied on their neighbours from. In the chess section of the poem, we zeroed in on a delicate, intricately tooled chess set, like a little Renaissance cityscape. For the hyacinth girl passage, we saw a montage of a young woman in an Eden-like sunny garden.

What White also deployed to great effect was a well-selected squad of talking heads, who range from Faber’s poetry editor to Vivien’s biographer and a drag star fascinated by the antique hermaphrodite seer Tiresias, who pops up, along with much else, in the poem. These really are talking heads, shot from the neck up and filling the screen, as if we are their intimates. It’s a simple but powerful technique. Fiona Shaw, in particular, a keen reciter of The Waste Land to audiences, offered an excellent entry point to the poem for somebody new to its compendious style, likening it to being on Instagram, with windows into other worlds you skip back and forth between.

Binding the whole together was a yearning soundtrack by Max Richter, who had his own odd role to play in the story, having intoned the poem in the small hours over the Tannoy at a petrol station where he was working as a schoolboy. I am agnostic about Richter’s work, but here it was a perfect choice, a poignant stream that ebbs and flows but doesn’t arrive anywhere. Which is an audio equivalent of the blasted lives and sadnesses Eliot describes in the poem, not least his own.

Best of all, White gave pride of place to Eliot’s recording of the work in his unmistakable stateless voice, by turns arch and gruff, passionate and despairing, but always musical and weirdly thrilling, even at its darkest. Section by section, with the poet’s commanding voice as a guide to the tone he intended, the documentary teases out the poem’s layers and kaleidoscopic references, adding to them footnotes of its own. You come away haunted by both the documentary and the poem.

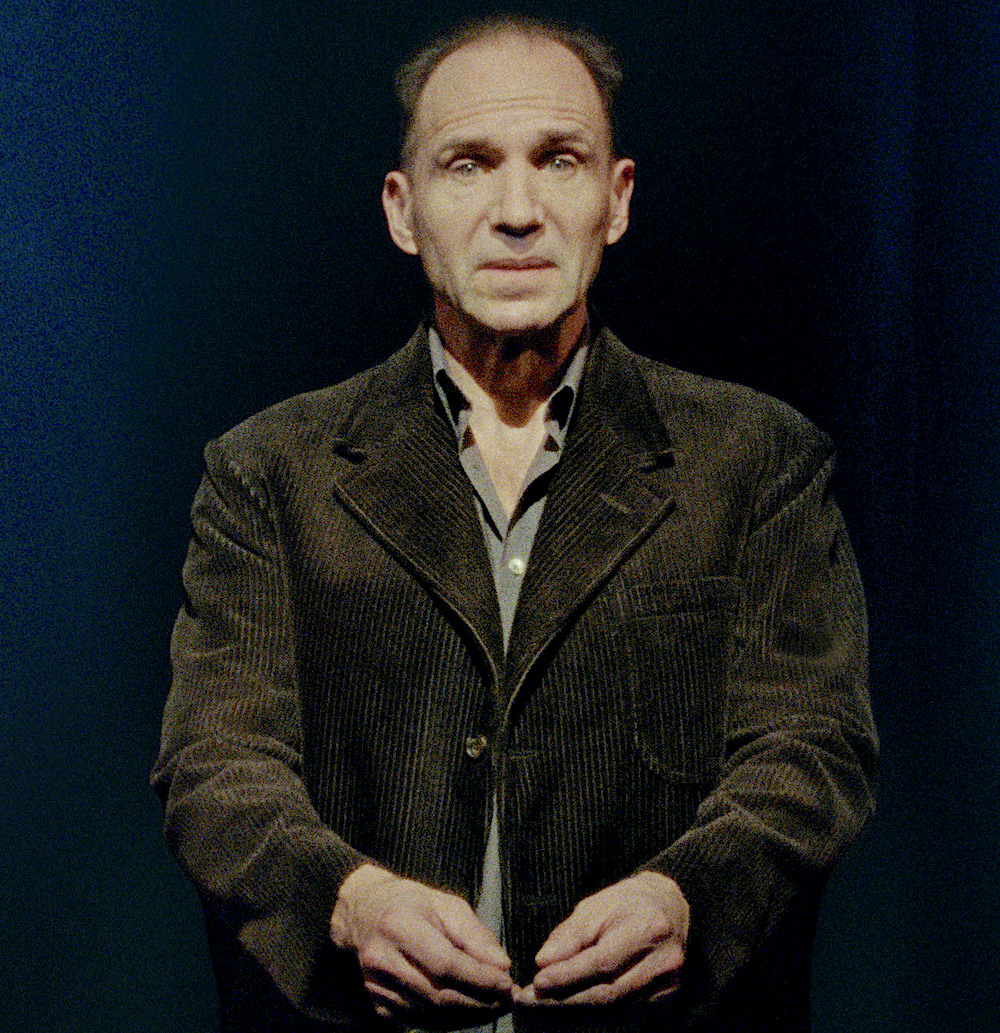

Who better to recite another Eliot magnum opus to today’s live audiences than Ralph Fiennes (pictured right), a man with an equally magisterial voice that can move from nuance to menace and back on a dime? The actor’s performance of Eliot’s Four Quartets has already toured to various theatres, and has now been filmed by his director sister Sophie (BBC Four, ★★).

Who better to recite another Eliot magnum opus to today’s live audiences than Ralph Fiennes (pictured right), a man with an equally magisterial voice that can move from nuance to menace and back on a dime? The actor’s performance of Eliot’s Four Quartets has already toured to various theatres, and has now been filmed by his director sister Sophie (BBC Four, ★★).

It was watching this film that convinced me certain poems should either be simply read out loud (preferably in a darkened room) or consumed quietly to oneself. In the case of Eliot, the listener needs to open up to the words and let them flow past. What they don’t lend themselves to is dramatisation, as if there is a kind of narrative to be winkled out of them that can be spoken almost as prose. They may seem conversational, but they don’t work as dialogue.

Fiennes’s voice has both a musicality and a precision that serve the poet well – and I would love a simple audio recording of the performance. But he is also called upon to move, gesture, caper and, at one point, drop into a wide-legged squat yelling “Dung!” It’s as if the words aren't enough. But this theatrical “business” distracts from the poem's images and tone. And the approach is literal to a fault: where the text says “dark, dark, dark”, the stage lighting goes out. When it refers to things being “lower”, Fiennes sits down, and so on.

Each of the poems becomes a mosaic of acted-out fragments, briefly vivid at times but indigestible as a whole. Just give me a masterful voice to focus on, without the trimmings. The poems may be rooted in Eliot’s experience of the world, but they only come alive in an otherworldly place, in our mind’s eye.

Add comment