When it comes to a blank page, artists and poets lead different kinds of lives and leave different kinds of marks. One for the eye, one for the ear, but both dependant on the thrill of recognition. The word, like paint, can be worked and reworked until the delight of a new image, a fresh metaphor in its right setting rings from the twisted garbage of lines in a notebook.

Back in the days of Surrealism, Revardy and Breton delighted in new images cast from the most disparate material. I understand that thrill. It’s what makes poetry worth reading. Art and poetry are concentrated mediums. Their engine is metaphor and the power of metaphor cannot be diminished. It’s a fixed star that doesn’t go out. You can see that in the cave art and objects of the Mesolithic – for image contains metaphor as much as the word.

Poetry is a portable art – you need no studio, no room, no lights, no crew

Metaphor is the root and branch of poetry, of thought itself, the first human tool that permitted us to imagine the potential state of tools and ornaments from raw materials. Its state of potential is a steady state, unfettered by the hated Second Law of Thermodynamics, a parallel dimension (notebooks out, quantum physiscists) and even when you’ve drafted a poem or made the permanent marks of an image, the thrill of potential – for viewer and maker – must remain with the work, or you’ve failed, and all your darlings are dead, and must be destroyed.

A lot of great poems are intensely visual, so it’s odd that there are so few practicing artist-poets. It’s an alliance of wonderful potential. Here’s Annie Freud, one of the very few who makes art and poetry professionally – her first sold works were on clothing, then on paper and board, before she published three acclaimed books of poems with Picador. The next will combine her poetry with eight new paintings.

A lot of great poems are intensely visual, so it’s odd that there are so few practicing artist-poets. It’s an alliance of wonderful potential. Here’s Annie Freud, one of the very few who makes art and poetry professionally – her first sold works were on clothing, then on paper and board, before she published three acclaimed books of poems with Picador. The next will combine her poetry with eight new paintings.

“Painting and poetry together are seen as transgressive,” she says, “and when I look at that way of thinking, what I’m really thinking of is what the English Reformation did to the visual arts, the enormous destruction of a self-belief in visual work. The effect of that cruelty and iconoclasm has never died. It’s what drives that idea of transgression.

“Because it’s prohibited and because I feel I’m aging, I don’t care that you’re not meant to put images with poems. Where they work is where they belong together. My poem Moths on a Blue Path belongs to that painting by Michael Wishart (pictured below).

“I write my poems as little films. I see it as a visual thing, in front of my eyes, and that tells me what the poem might be about. The painting of Dave’s hands. For me what was fantastic was seeing these marvellous hands shaped by physical toil and beautified by the wear and tear of work holding these apples. It was a mixture of one nature with another. It made me feel those were things that mattered to me.

“I write my poems as little films. I see it as a visual thing, in front of my eyes, and that tells me what the poem might be about. The painting of Dave’s hands. For me what was fantastic was seeing these marvellous hands shaped by physical toil and beautified by the wear and tear of work holding these apples. It was a mixture of one nature with another. It made me feel those were things that mattered to me.

“Having seen a vase full of roses outside a shop, looking a very particular way, I take that away with me and wonder what it’s making me think about human life. But it’s only because I saw them, I could not ever imagine them. It’s how the visual experience of real life, when you are alert, can collect your thoughts and make life worth living. I suppose it’s what I live for. If I’m at a party and I see a coat stand draped in coats and scarves, I see a kind of orgy going on.”

Moths on a Blue Path

After Moths on a Blue Path by Michael Wishart

Having drunk the half-bottle of crème de menthe

that you found in the drinks cupboard after breakfast,

you drag along this path, your eyes fixed on the floor,

scouring for a gift among the gaudy snail shells,

empty acorn cups and coiled trails left by the worms.

It’s the hush of a Sussex summer’s day.

You’re down for the week and may stay longer.

The studio rent’s overdue and the curtains have gone

to the cleaners. Bobby’s in the South of France

and the club is closed till September the first.

Mother wrote full of enthusiasm about the new roses

and has promised a trip to Rottingdean.

What has made the moths come out in such numbers,

streaking the grass with their silvery eye shadow,

beating their wings in hapless frenzy,

ungainly in the hour of death? You hope

for something nice for lunch. A train crosses the Marsh.

The uniform greenness oppresses you.

There’s a tradition of poets who worked with artists – Picasso had a legion of French ones; while Ted Hughes’ Crow is incomplete without Leonard Baskin’s images. Contemporary poets such as Tamar Yoseloff use art as a source of inspiration; her collaboration with photographer Vici Macdonald (formerly, Hercules Editions) was shortlisted this year for the Ted Hughes Award.

Poet-artists are much more rare. William Blake glowers in his early 19th-century den; David Jones shimmers in the ethereal, air-blown work of the Thirties and Forties (pictured left, Aphrodite in Awlis), while from the 21st century’s small presses and online sites, Bobby Parker’s poetry, writings and images (pictured below right) hit a confessional, metaphysical, liminal vein, where anguish is another hallucination. Here’s Bobby on struggle for the image in both forms, forming slowly like coral…

Poet-artists are much more rare. William Blake glowers in his early 19th-century den; David Jones shimmers in the ethereal, air-blown work of the Thirties and Forties (pictured left, Aphrodite in Awlis), while from the 21st century’s small presses and online sites, Bobby Parker’s poetry, writings and images (pictured below right) hit a confessional, metaphysical, liminal vein, where anguish is another hallucination. Here’s Bobby on struggle for the image in both forms, forming slowly like coral…

“Behind the image there are fear and addiction. Fear of the world, the mystery of nature and people and feelings. Fear of losing the ability to produce imagery, through words or other mediums - accidents, experiments, off the page, under the streets, talking to the saddest looking people on the train.

“You are addicted to the moment when the image burns, cries, pulls the face of a dream so close you can taste the things it loves. Those spaced-out seconds when you breathe high and deep and know that somewhere soon something strange will happen because of your image, then you push it to the side and wait for the next one.

“You wait, absorb the abstract, grow fat, wait in borderline hysterical vertigo for the next pile of words, the next picture. Books are published. Images are liked, bought and shared, and people want to be around you because your fear inspires them.

“But you don't know anything about that. Your fingers clenched around a Poundland paintbrush, or squeezing a mouse with red eyes, or poised above the cold keys, and that fucking cursor flashing forever on the blank screen. Where are you?

“Between words and pictures you are temporary, a ghost, gambling with time. Your wife looks rather sad - something moves. Your daughter is crying – something smiles. The system is flawed. A jackpot affects everybody. Life melts under your tongue.”

It is this writer’s experience that making images – artistic images – empties the mind while writing images tends to focus the mind down a steep and narrow way. I drew before I could read or write. Most humans do, but I was remedial and needed extra help to learn how to turn that undergrowth of black marks into clear signals. I was seven before I could read my first story – Rapunzel, the Ladybird edition with its vivid watercolours. That Well-Loved Tale, the words and the pictures, is probably an important inspiration. Those bottomless, endlessly vibrating fairy tales are, to me, like the cave art at Chauvet.

Poetry is a portable art – you need no studio, no room, no lights, no crew; just a pen and a sheet of paper. I make art the same way, but with watercolour and pen. Portable mediums that fit in a shoulder bag, that dry fast and keep their pigments, like the green of that bewitching Rapunzel. Stuff that you can do standing up. Over the past decade, I've made film poems – shot, edited, soundtracked and conceived them. The likes of Flowers, and Danebury Ring are moving poems, art loops for public display. In the past few years, they have been shown at festivals worldwide.

Poetry is a portable art – you need no studio, no room, no lights, no crew; just a pen and a sheet of paper. I make art the same way, but with watercolour and pen. Portable mediums that fit in a shoulder bag, that dry fast and keep their pigments, like the green of that bewitching Rapunzel. Stuff that you can do standing up. Over the past decade, I've made film poems – shot, edited, soundtracked and conceived them. The likes of Flowers, and Danebury Ring are moving poems, art loops for public display. In the past few years, they have been shown at festivals worldwide.

I was working in the art world when I first started publishing poems, at Karsten Schubert’s in the Eighties and early Nineties, the crucible of BritArt. Damien, Sarah, Gary, Matt, Michael and co were about to become celebrities, and fuse the conceptual and pop with a creative director’s eye for a lifetime’s branding.

I was hanging some of their work and publishing in new poetry magazines – The Echo Room, Dog, The Wide Skirt and others – and picking up on the plasticity of the YBA’s ideas. But I couldn’t catch a hold of the valuable fetish value of their work. Poetry isn’t an object in the same way – it’s a multiple, at best. Unless you choose to hang poems in editions of one, with no duplication permitted. I’ve considered it. Now I’ve done it.

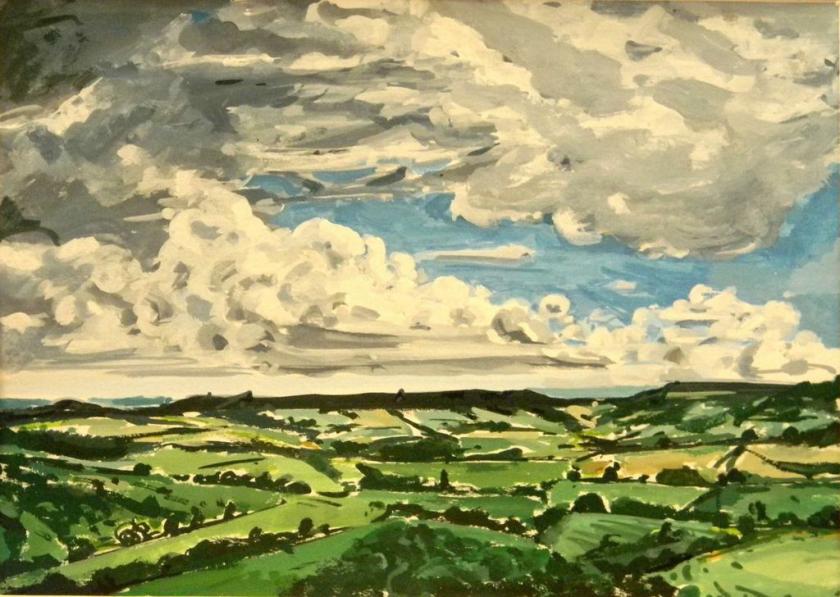

Until 23 February, 15 paintings and 15 poems hang in the downstairs space at Slader’s Yard in West Bay, Dorset. It’s their winter show, but these are summer and spring pictures, and what’s important is that they’re field paintings, not studio bound, not taken from secondary sources, but from direct contact. Contact sheets. They’re made in the field, a field work open to the elements and senses. Not just the eye, but the hairs on the back of the hand and the neck, the smell of the air, the cold in your fingers, the direction of wind. How you came to be here. I’m looking for impact, not representation.

Each poem goes with a specific picture. I’ve married them off. The texts are printed on transparent paper and mounted on poplar boards. I’ve mulled over the proper way of combining poems and art for years without feeling an elegant solution. But somehow we walked right into it at Sladers Yard. I call it sensationalism. The intention is to pull the feel and atmosphere of a place into the picture, into a poem, so that what you see retains the impact of what you saw and how you felt over the time you were there. I’m looking for the viewer to see their own images in real time. They’re not illustrations at all; they’re beings. They work as a kind of transport. It’s the same with the poems. It’s not about text and illustration but a singularity of the two. The one ignites the other, and with both barrels, so that they move together.

Deep Blue

With Charlton Down at Dusk I

Tonight the sky is very blue and very clear –

too clear for us. Some nights you see too much

reach too far, feel the fear of a trembling star,

the correspondence course of a lover’s touch.

There’s a new distance in the air and where

streetlighting ends the summer corn’s

been carried in, fat golden chords of heat and sun

so let it come down on the turning blades that flare

between us, the hand that keeps on moving free,

brushing over the ears and beards and seeds and fruits,

over swollen rivers and sleeping roots.

Dig up a tree for its underworld calligraphy.

Small words are like the sky tonight, blue and very clear.

All life is yours, though death is near.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment