A Bigger Splash... opens with Hans Namuth’s famous 1951 film of Jackson Pollock balletically dripping, flicking and pouring paint onto the canvas at his feet. Beneath the screen a long, scroll-like painting by Pollock lies on the gallery floor. The arrangement implies that this could be the painting the artist is creating on film while, subliminally, another message is being conveyed. The screen has pride of place, so all eyes are on the heroic artist; he is of prime importance and the work is perceived as a byproduct of his creative drive.

Welcome to Action Painting – a phrase coined by American critic Harold Rosenberg – and to the concept of painting as a form of performance. Pollock’s engagement with the canvas was primarily physical rather than cerebral. (Pictured right: Summertime 9A (1948) installation shot. Tate collection © Pollock-Krasner Foundation) The painting was the result of improvisation – a dance involving the transfer of paint from brush, can or stick to canvas. And since nothing was preconceived – there were no preparatory drawings or sketches – the white expanse became, according to Rosenberg, "an arena in which to act... What was to go on the canvas,” he famously wrote, “was not a picture but an event.” The resulting image, therefore, is a record or trace of that interaction.

Welcome to Action Painting – a phrase coined by American critic Harold Rosenberg – and to the concept of painting as a form of performance. Pollock’s engagement with the canvas was primarily physical rather than cerebral. (Pictured right: Summertime 9A (1948) installation shot. Tate collection © Pollock-Krasner Foundation) The painting was the result of improvisation – a dance involving the transfer of paint from brush, can or stick to canvas. And since nothing was preconceived – there were no preparatory drawings or sketches – the white expanse became, according to Rosenberg, "an arena in which to act... What was to go on the canvas,” he famously wrote, “was not a picture but an event.” The resulting image, therefore, is a record or trace of that interaction.

For subsequent generations the issue was how to respond to this cataclysmic shift in thinking about the nature of painting. Many went down the route of performance and the exhibition attempts to provide an overview of the transition from painting to performance. The aim is to be comprehensive and, since artists in China, Japan, Korea, Eastern and Western Europe, Cuba and Brazil, as well as Britain and the States were exploring the potential, there’s a lot of ground to cover. In France, Yves Klein employed models to smother their bodies in paint and press themselves against paper or canvas to leave an imprint. But not enough space has been allocated, so most people are represented by just one or two images and a resumé of their life’s work. It's far too much to take in, especially if the material is new to you, and there are too few images to whet your appetite for swotting.

It feels particularly relentless because little-known artists like Wiktor Gutt are given equal billing with major figures like Bruce Nauman, so there’s no change of pace or shift in emphasis. (Pictured left: Ana Mendieta Self-Portrait with Blood (1973) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta, courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York). And why have some key participants been left out? Whatever happened to Happenings? Robert Rauschenberg, Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg – who staged performances for live audiences – are inexplicably missing along with any mention of Fluxus artists like Yoko Ono. Remember John Lennon climbing a white ladder to read the word “Yes” written on a white painting tacked to the ceiling?

It feels particularly relentless because little-known artists like Wiktor Gutt are given equal billing with major figures like Bruce Nauman, so there’s no change of pace or shift in emphasis. (Pictured left: Ana Mendieta Self-Portrait with Blood (1973) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta, courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York). And why have some key participants been left out? Whatever happened to Happenings? Robert Rauschenberg, Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg – who staged performances for live audiences – are inexplicably missing along with any mention of Fluxus artists like Yoko Ono. Remember John Lennon climbing a white ladder to read the word “Yes” written on a white painting tacked to the ceiling?

There’s no sign of Carolee Schneemann (who painted while swinging naked from a rope) or Orlan (who underwent plastic surgery so her face would conform to an ideal espoused by Renaissance painters like Botticelli). Also absent are Luca Fontana (who slashed his canvases) and Piero Manzoni (who notoriously canned his shit) along with Gustav Metzger (who attacked a giant painting with acid during his Destruction in Art Symposium of 1966).

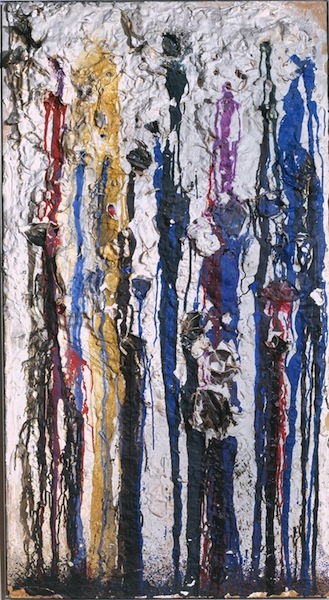

After three rooms of bodies covered in paint and faces plastered in make-up, everything begins to merge into a seemingly endless orgy of narcissism. (Pictured below right: Poured Painting (1963) by Hermann Nitsch © DACS) With all this self-regarding sensuality, one might expect a climax to follow, but Part Two of the exhibition is a damp squib. Here the chosen few have been given a room each; but compared with what has gone before, the installations are feeble in the extreme.

The exceptions are Joan Jonas and Marc Camille Chaimowicz, who have been airlifted from Part One where they belong, and Lucy McKenzie. In Brussels, McKenzie learned techniques for reproducing the appearance of wood, marble, glass and so on. She uses these prodigious skills to faithfully reproduce real and imagined interiors, but the only link her traditional paintings have with performance is their huge scale. They are like theatre sets waiting to be peopled with performers and Lucile Desamory plans to use them as a backdrop for a forthcoming film. Karen Kilimnik’s installation is a (deliberately) idiotic pastiche of a set for Swan Lake, so relating to theatre rather than painting. By fixing a line of blue tape round the wall and across 12 suspended mirrors, Polish artist Edward Krasinski hopes to disorientate the viewer with multiple reflections and perspectives. When was the first mirror installation created, I wonder? Was it Robert Morris’s Mirrored Cubes of 1965 and how many hundreds have there been since then?

The exceptions are Joan Jonas and Marc Camille Chaimowicz, who have been airlifted from Part One where they belong, and Lucy McKenzie. In Brussels, McKenzie learned techniques for reproducing the appearance of wood, marble, glass and so on. She uses these prodigious skills to faithfully reproduce real and imagined interiors, but the only link her traditional paintings have with performance is their huge scale. They are like theatre sets waiting to be peopled with performers and Lucile Desamory plans to use them as a backdrop for a forthcoming film. Karen Kilimnik’s installation is a (deliberately) idiotic pastiche of a set for Swan Lake, so relating to theatre rather than painting. By fixing a line of blue tape round the wall and across 12 suspended mirrors, Polish artist Edward Krasinski hopes to disorientate the viewer with multiple reflections and perspectives. When was the first mirror installation created, I wonder? Was it Robert Morris’s Mirrored Cubes of 1965 and how many hundreds have there been since then?

The impression given by Part Two is that Painting after Performance has been replaced by cliché-ridden installations, which is complete nonsense, of course. Dozens of artists continue to paint as if the authority of the medium had never been questioned. Gerhard Richter, Marlene Dumas, Sean Scully, Peter Doig, Glenn Brown, Maria Lassnig, Georg Baselitz, Gary Hume, Fiona Rae and Tomma Abts are just a few of the hundreds who are still very much alive and well.

So who could have been included in Part two? (Pictured left: Shooting Picture (1961) by Niki de Saint Phalle © The Estate of Niki de Saint Phalle) Responding to the challenge of performance and installation art, some emphasise the physicality of their paintings. Angela de la Cruz rips her canvases off their stretchers and contorts them into sculptural forms. Anselm Kiefer loads his surfaces with ash, plaster, earth or vegetation and attaches burned books, clothing or model ships to create impasto reliefs whose huge scale and dominant physical presence implies moral and philosophical weight.

So who could have been included in Part two? (Pictured left: Shooting Picture (1961) by Niki de Saint Phalle © The Estate of Niki de Saint Phalle) Responding to the challenge of performance and installation art, some emphasise the physicality of their paintings. Angela de la Cruz rips her canvases off their stretchers and contorts them into sculptural forms. Anselm Kiefer loads his surfaces with ash, plaster, earth or vegetation and attaches burned books, clothing or model ships to create impasto reliefs whose huge scale and dominant physical presence implies moral and philosophical weight.

Mariele Neudecker responds to 19th-century painter Casper David Friedrich by making abject little models of landscape and elegiac videos of sunrises that seem to mourn the loss of the German romantic spirit. James Turrell bathes viewers in coloured light in installations that are like all-encompassing paintings, while Amikam Toren and Mel Bochner stress the conceptual underpinnings of paintings that explore the relationship between words and images.

But the real proponents of Painting After Performance are artists for whom the process of making the work directly governs the end product. Callum Innes dribbles turpentine down his canvases to leech out the colour in runnels that resemble rain or tears. Ian Davenport tips, pours and puddles paint onto fibreboard to create stripes, veils and pools of intense colour.

One of the few paintings in the exhibition is David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash a traditional picture that bears no relationship either to Abstract Expressionism or performance art. So why is it included – to provide a neat title that will attract the crowds? What a shame that this challenging subject should have been treated with such hazy regard for the premise behind its own title.

- A Bigger Splash: Painting After Performance at Tate Modern until 1st April 2013

Watch Hans Namuth's film on Jackson Pollock

Add comment